Long wandering, my heart stays drunk with care,

The lofty tower sinks in fading air.

The Yellow River cuts through land and sea,

While Hua Peak guards the western frontier free.

A thousand sails dwindle toward distant quest,

A lone bird drifts late, lost from its nest.

Year after year, my dreams turn vain -

The eastern stream mocks my unused gain.

Original Poem

「登鹳雀楼」

耿玮

久客心常醉,高楼日渐低。

黄河经海内,华岳镇关西。

去远千帆小,来迟独鸟迷。

终年不得意,空觉负东溪。

Interpretation

This "On Climbing Stork Tower" is not Wang Zhihuan’s celebrated five-character quatrain, but a seven-character regulated verse by Geng Wei composed atop the same landmark. Around the Dali era (766–779), the poet journeyed to Puzhou (modern Yongji, Shanxi) and climbed Stork Tower. Gazing upon the mountains and rivers, he was stirred by the view to express his solitary wanderer’s heart and the anguish of unrecognized talent. The poem interweaves majestic landscapes with inner melancholy, exemplifying Geng Wei’s signature style of vista-inspired lyricism—its tone somber, its vision vast.

First Couplet: "久客心常醉,高楼日渐低。"

Jiǔ kè xīn cháng zuì, gāo lóu rì jiàn dī.

Long a wanderer, my heart drowns in daze;

The towering height sinks lower day by day.

The opening lines confront exile’s weight: "drowns in daze" (心常醉) twists the cliché of drunken solace into a metaphor for numb despair. The subjective distortion of the tower "sinking" (日渐低) externalizes psychological collapse, where even solid architecture bends under solitude’s gravity. Geng Wei’s spatial irony here preludes the poem’s tension between grandeur and fragility.

Second Couplet: "黄河经海内,华岳镇关西。"

Huáng Hé jīng hǎi nèi, Huà Yuè zhèn guān xī.

The Yellow River veins the land’s broad breast;

Mount Hua anchors the frontier’s west.

These lines pivot to cosmic scale: the Yellow River’s "veining" (经) suggests lifeblood of the empire, while Mount Hua’s "anchoring" (镇) evokes both geological and cultural steadfastness. Yet this cartographic majesty—rendered through parallel syntax—underscores the poet’s own rootlessness. The couplet’s tectonic imagery becomes a silent rebuke to his unstable fate.

Third Couplet: "去远千帆小,来迟独鸟迷。"

Qù yuǎn qiān fān xiǎo, lái chí dú niǎo mí.

A thousand sails dwarf to nothing, gone;

One belated bird drifts lost, alone.

The gaze shifts to vanishing horizons: sails shrinking (千帆小) mimic eroded hopes, while the "belated bird" (独鸟迷)—a self-portrait—embodies directional despair. The juxtaposition of plural "sails" and singular "bird" sharpens the contrast between society’s departures and the poet’s irreducible isolation. Time and space conspire in this quiet apocalypse.

Fourth Couplet: "终年不得意,空觉负东溪。"

Zhōng nián bù déyì, kōng jué fù Dōng Xī.

Year-round, fortune frowns askance;

Now I shame Dongxi’s lost romance.

The finale confesses failure: "fortune frowns" (不得意) generalizes lifelong frustration, while "Dongxi" (东溪)—a symbol of abandoned eremitic ideals—condemns his compromises. The verb "shame" (负) pierces the poem’s contemplative surface, revealing a wound that landscape cannot heal. The closing sigh hangs like the tower’s shadow at dusk.

Holistic Appreciation

This poem uses the act of ascending a tower as its surface subject while gradually unfolding deeper reflections on the poet’s life. The opening couplet begins with the heart shaping the scene, emphasizing the loneliness of being adrift in a foreign land. The second couplet depicts vast rivers and mountains, revealing the grand ambitions within the poet’s chest. The third couplet shifts to dynamic details, conveying solitude and hesitation. Finally, the closing lines directly express the poet’s emotions, ending with "a hollow realization"—a poignant conclusion that lays bare the profound disillusionment born from the gap between ideals and reality. The poem masterfully balances movement and stillness, grandeur and intimacy, interweaving majestic landscapes with deep melancholy. Geng Wei skillfully connects the magnificence of nature with his own wandering existence, mirroring the isolation and defiance of a talented man unrecognized in his time.

Artistic Merits

The poem’s most striking feature is its fusion of scene and emotion, blending the tangible and the abstract. The Yellow River and Mount Hua, the thousand sails and the lone bird—all are real sights, yet through the poet’s gaze, they become psychological reflections. The illusory "lowness" of the tower symbolizes suppressed aspirations, demonstrating how scenery bends to emotion. Moreover, the poem’s sentiment deepens progressively, moving from distant to intimate. Its structure adheres to strict parallelism, with restrained allusions, measured phrasing, and a rhythm that flows steadily yet carries subtle undulations—hallmarks of Geng Wei’s "quietly desolate and understated" artistic style.

Insights

This poem offers a window into the soliloquy of a gifted mind grappling with life’s disappointments. Gazing afar from the tower, the poet beholds grandeur but harbors sorrow, prompting reflection: human existence seldom aligns ambition with circumstance, and true resilience lies in how one settles the heart and preserves integrity amid adversity. Though unfulfilled, Geng Wei inscribes his aspirations into verse, entrusting them to the mountains and rivers—a testament to unyielding character.

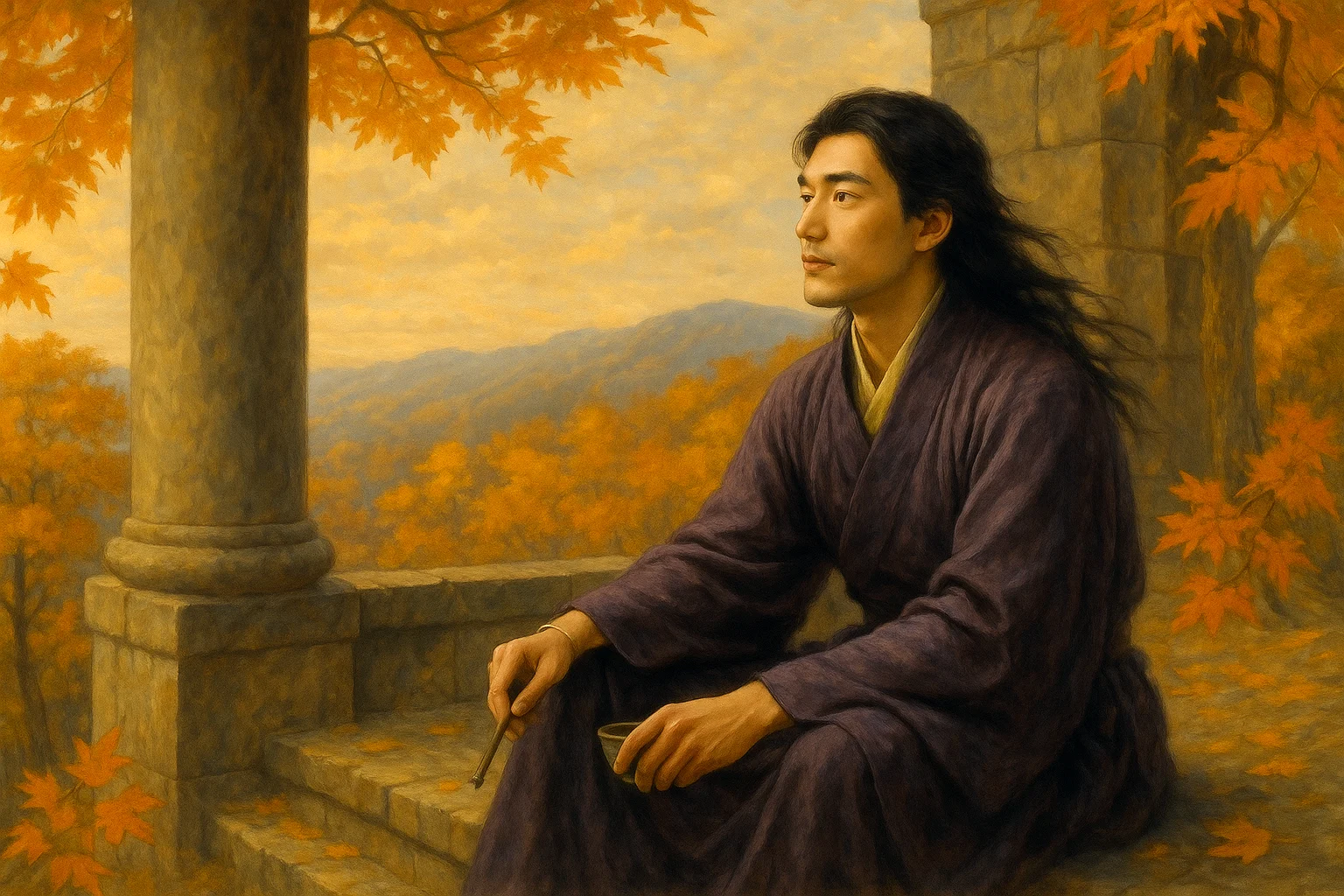

About the Poet

Geng Wei (耿湋, dates unknown), a Tang dynasty poet from Yongji, Shanxi, was among the "Ten Great Talents of the Dali Era." Renowned for his mastery of five-character regulated verse, his poetry is distinguished by its economical diction and tranquil imagery. While the prevailing style of Dali poetry tended toward austerity and desolation, Geng Wei developed a distinctive voice marked by understated naturalism.