Her dress shed fragrance on the lake;

The Southern soldiers took the capital at daybreak.

It would be a shame for the Southern king to win

The Eastern Kingdom by a lady fair and thin.

Original Poem

「馆娃宫怀古五绝 · 其一」

皮日休

绮阁飘香下太湖,乱兵侵晓上姑苏。

越王大有堪羞处,只把西施赚得吴。

Interpretation

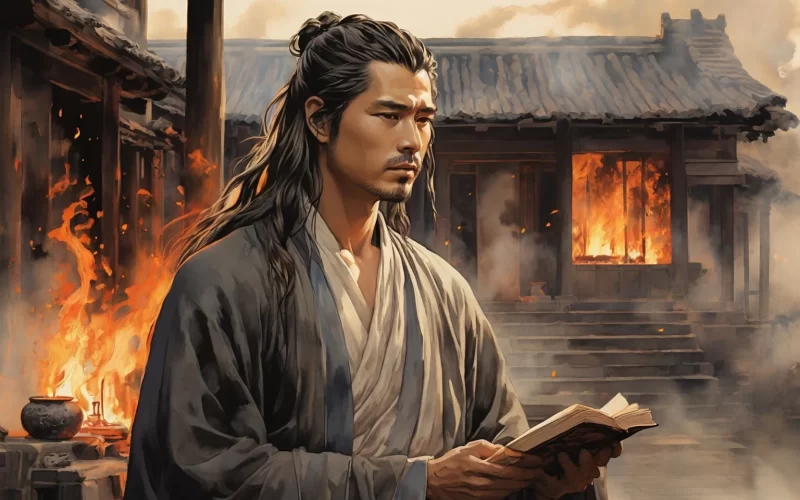

Composed during Pi Rixiu's tenure as Suzhou governor, this historically charged poem uses the ruins of the Palace of Wa (built by King Fuchai of Wu for his concubine Xishi) as a lens to examine the fall of kingdoms. Through concise yet layered language, the poet reveals how indulgence leads to downfall, offering veiled criticism of contemporary politics.

First Couplet: "绮阁飘香下太湖,乱兵侵晓上姑苏。"

"Perfumed towers wafted scent to Taihu's shore, While rebel troops stormed Gusu at daybreak's hour."

The opening juxtaposes decadence and destruction: the first line paints the palace's extravagance (香 xiāng - fragrance wafting carefree), while the second delivers the brutal dawn attack (乱兵 luànbīng - chaotic soldiers). The temporal parallel—pleasure drifting south as invaders advance—underscores Wu's fatal negligence.

Second Couplet: "越王大有堪羞处,只把西施赚得吴。"

"Shame stains Yue's king—his triumph came too cheap: With but one woman, all of Wu was reaped."

Here, Pi Rixiu wields irony like a dagger. By calling Yue's victory "shameful" (堪羞 kānxiū), he sarcastically highlights Wu's greater humiliation: losing an empire to a single beauty. The verb 赚 (zhuàn - "swindle") reduces Xishi to a transaction, mocking Fuchai's blindness to strategy beneath seduction.

Artistic Merits

This exquisite five-line quatrain demonstrates masterful conception through historical allegory. The opening juxtaposition of perfumed pavilions with battlefield flames creates a scene where decadence and crisis coexist. Employing subtle indirection, the poet ostensibly criticizes Yue while actually satirizing Wu, embedding political commentary within historical narrative through metaphorical implication. The concise yet profound language and vivid situational contrasts heighten the satirical effect while deepening thematic resonance, making this a structurally compact and richly ironic masterpiece of the five-line form.

Holistic Appreciation

Pi Rixiu appropriates the historical downfall of Wu and Yue, superficially narrating how the Yue king used Xi Shi to conquer Wu while fundamentally exposing King Fuchai's fatal obsession with beauty that doomed his kingdom. The contrasting imagery of "fragrant silken towers" and "rebel troops at dawn" sharply opposes Wu's palace pleasures with national collapse, creating tightly composed, multi-layered visuals. The poem's profound allegory and potent satire, expressed through economical yet emotionally charged language, showcase the poet's exceptional historical insight and artistic expression.

Insights

Using King Fuchai's infatuation with Xi Shi and subsequent downfall as historical mirror, the poem warns how a nation's fate often hangs on a ruler's momentary decision. Though beauty may topple cities, its indulgence at the expense of governance becomes a nation's ruin. Through historical analogy, the poet reminds us: statecraft requires temperance and self-reflection—personal desires must never override national interests. Only by prioritizing the state and its people can lasting stability be achieved.

Poem translator

Xu Yuanchong (许渊冲)

About the Poet

Pi Rixiu (皮日休, c. 834-883), a Late Tang dynasty poet and scholar from Xiangyang, Hubei. He obtained the jinshi degree in 867 (8th year of Xiantong era). His poetry carried on Bai Juyi's New Yuefu tradition. After the failed uprising, he was presumably executed, with most of his works lost. The Complete Tang Poems preserves over 300 of his poems.