Li Bai would turn sweet nectar into verses fine.

Drunk in the capital, he'd lie in shops of wine.

Even imperial summons proudly he'd decline,

Saying immortals could leave the drink divine.

Original Poem:

「饮中八仙歌 · 李白」

杜甫

李白一斗诗百篇,长安市上酒家眠。

天子呼来不上船,自称臣是酒中仙。

Interpretation:

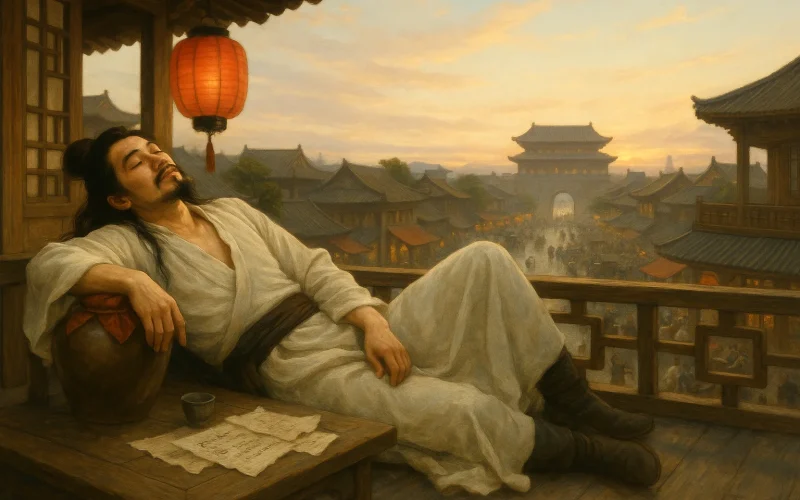

This poem is from Du Fu’s "Songs of Eight Immortal Drinkers", composed around 746 AD during the Tianbao era. At that time, Li Bai had just ended his tenure as a scholar at the Imperial Academy and left Chang'an under the pretext of being "dismissed with rewards." Du Fu, who had recently arrived in the capital, witnessed the free-spirited and unrestrained revelry of this group on the eve of the decline of the Tang Dynasty's golden age. The eight immortals of wine represent a snapshot of the flourishing Tang spirit, and Li Bai, featured last, is portrayed with the most vivid strokes—these four lines are both a heartfelt sketch of his close friend and an elegy for the free spirit of an era.

First Couplet:“李白一斗诗百篇,长安市上酒家眠。”

With a jug of coarse wine, a hundred poems bloom, splendid; beneath the tavern signs in Chang'an's western market, he sleeps drunk, his clothes steeped in the trials of urban life.

Du Fu uses the "jug of wine" as a measure of poetic intensity. The continuous consumption of low-alcohol yellow wine (around 3-5% alcohol) during the Tang Dynasty was, in fact, a physical immersion into the mundane world. Li Bai chose the western market taverns, frequented by foreign merchants, as his creative space, as if moving his study into the heart of the bustling city—where the elegant hats of scholars mingled with the bells of merchant caravans, creating a poetry that transcended social classes. Drunkenness was not a sign of decadence but a gentle rebellion against the constraints of Confucian rituals, expressed through a seemingly carefree demeanor.

Second Couplet:“天子呼来不上船,自称臣是酒中仙。”

The emperor summons him to board the royal boat, but he refuses, leaning drunkenly on the railing; declaring, "I am an immortal of wine," he reduces imperial majesty to mere smoke.

During imperial banquets on Xingqing Lake, where strict etiquette demanded formal attire and measured steps, Li Bai, staggering in drunkenness, dissolved these formalities. His self-proclamation as an "immortal of wine" is a masterful rhetorical move—he rivals the emperor as a Taoist immortal while maintaining a façade of respect with the term "servant." This wisdom of using "drunkenness as a shield" achieves a delicate balance between audacity and restraint, offering a classic model for later scholars to resist authority.

Writing Characteristics:

- The Tang Variation of Wei-Jin Spirit: The solitary anger of Ruan Ji, drunk in taverns, and the cold arrogance of Ji Kang, refusing official posts, are transformed in Li Bai into a radiant and unrestrained boldness. The openness of the Tang Dynasty allowed scholars' rebellion to be expressed with greater ease.

- The Poetic Transformation of Taoist Aesthetics: The concept of the "true immortal" from Sima Chengzhen’s "Treatise on Sitting in Oblivion" is deconstructed by Li Bai into the worldly practice of the "immortal of wine." Viewing the world through drunkenness reflects a value system that transcends the mundane.

- The Multifaceted Spirit of Scholars: Unlike the Buddhist tranquility of Wang Wei in "After the Rain on the Empty Mountain", Li Bai, through his dynamic drunkenness, expands the boundaries of the scholar's image—writing while drunk, living with audacity, infusing Chinese culture with a powerful vitality.

Insights:

Li Bai’s drunken life offers a timeless spiritual mirror for modern people. In a performance-driven society, his existence reminds us that true freedom lies not in escaping rules but in creating poetic spaces within their gaps. The hustle and bustle of urban life hides sources of inspiration, and a tipsy state may be a remedy against alienation. The self-proclamation of being an "immortal of wine" is a spiritual declaration—even if the body is trapped in the walls of mortgages and KPIs, the soul can still soar through poetry and wine. This wisdom of navigating between engagement and detachment is a precious legacy left by Tang scholars for modern generations.

Poem translator:

Xu Yuan-chong (许渊冲)

About the poet

Du Fu (杜甫), 712 - 770 AD, was a great poet of the Tang Dynasty, known as the "Sage of Poetry". Born into a declining bureaucratic family, Du Fu had a rough life, and his turbulent and dislocated life made him keenly aware of the plight of the masses. Therefore, his poems were always closely related to the current affairs, reflecting the social life of that era in a more comprehensive way, with profound thoughts and a broad realm. In his poetic art, he was able to combine many styles, forming a unique style of "profound and thick", and becoming a great realist poet in the history of China.