New Year's only deepens my longing,

Adds to the lonely tears of an exile

Who, growing old and still in harness,

Is left here by the homing spring...

Monkeys come down from the mountains to haunt me.

I bend like a willow, when it rains on the river.

I think of Chia Yi, who taught here and died here -

And I wonder what my term shall be.

Original Poem

「新年作」

刘长卿

乡心新岁切,天畔独潸然。

老至居人下,春归在客先。

岭猿同旦暮,江柳共风烟。

已似长沙傅,从今又几年。

Interpretation

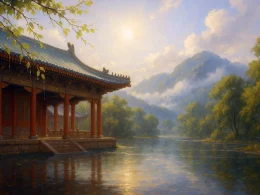

Composed during Liu Changqing's exile as a minor official in Nanba County of Panzhou, this poem reflects the poet's state of mind during Emperor Suzong's reign when he was unjustly banished to the southern frontier. As the Lunar New Year approached - traditionally a time for family reunion and renewal - the poet found himself stranded in a distant land, his career prospects dim and homesickness acute. Through layered emotional progression and historical allusion to Jia Yi, the poem reveals Liu's profound solitude and indignation, standing as a classic example of seasonal melancholy and allegorical expression.

First Couplet: "乡心新岁切,天畔独潸然。"

Xiāng xīn xīn suì qiè, tiān pàn dú shān rán.

New Year sharpens homesickness like knife / At sky's edge, alone I weep for life

The opening immediately establishes temporal and emotional coordinates. "New Year" (新岁) - normally celebratory - becomes ironic counterpoint to exilic sorrow. "Sky's edge" (天畔) spatializes both geographical and existential marginalization, while the unadorned "weep" (潸然) conveys raw vulnerability.

Second Couplet: "老至居人下,春归在客先。"

Lǎo zhì jū rén xià, chūn guī zài kè xiān.

Aging yet beneath others I stay / Spring returns home while I'm kept away

This conceptual couplet juxtaposes human and natural cycles. The bitter paradox of seniority without status ("aging yet beneath") contrasts with spring's unimpeded return. That seasons journey home before exiled humans underscores bureaucratic cruelty through nature's indifference.

Third Couplet: "岭猿同旦暮,江柳共风烟。"

Lǐng yuán tóng dàn mù, jiāng liǔ gòng fēng yān.

Dawn to dusk with mountain apes I cope / Willows and I share river mist and hope

Southern exile's harsh reality emerges through primal companionship - apes replacing human society, river willows becoming confidants. "Share" (共) suggests forced intimacy with wilderness, where even weather patterns ("mist") become notable companions.

Fourth Couplet: "已似长沙傅,从今又几年。"

Yǐ sì Chángshā fù, cóng jīn yòu jǐ nián.

Like Jia Yi in Changsha cast / How many years must this exile last?

The historical allusion to Jia Yi - brilliant Han statesman banished to Changsha - elevates personal suffering into cultural paradigm. The rhetorical question "how many years" (又几年) transforms temporal uncertainty into existential dread, echoing through Chinese literary history.

Holistic Appreciation

The poem constructs an emotional crescendo from seasonal awareness (I), through social humiliation (II) and environmental adaptation (III), culminating in historical self-identification (IV). Liu masterfully inverts New Year symbolism - typically associated with renewal - into an occasion for measuring exile's duration. The progression from personal "weeping" to identification with Jia Yi's legendary suffering universalizes the experience, connecting Tang bureaucratic injustice to Han precedents.

Artistic Merits

- Temporal Paradox: Subverts New Year's celebratory expectations with exilic reality

- Nature's Cruelty: Spring's easy return highlights human institutional barriers

- Primal Imagery: Apes and willows replace human society in wilderness companionship

- Historical Resonance: Jia Yi allusion transforms personal complaint into cultural critique

Insights

Liu's poem speaks to all who measure personal stagnation against society's cyclical celebrations. His predicament mirrors modern experiences of professional disappointment during holidays, when social media's highlight reels exacerbate private struggles. The work suggests that true resilience lies not in denying suffering, but in framing it within broader historical patterns - understanding one's "Changsha exile" as part of civilization's recurring mistreatment of talent. Ultimately, the poem values emotional honesty ("weep") over forced optimism, offering permission to grieve life's unfairnesses.

About the poet

Liu Zhangqing (刘长卿) was a native of Xian County, Hebei Province. He studied at Mt. Songshan when he was young, and later moved to Jiangxi, where he received his bachelor's degree in 733 A.D. He also belonged to the Wang and Meng school of poetry. His poems belonged to the school of Wang and Meng, and he was most famous for his five-character poems, and was also most conceited, once thinking that he was "the Great Wall of five-character poems", which meant that no one could surpass him.

The poet naturally missed his hometown and his family in the New Year. But he was relegated to a distant land in the sky, thousands of miles, want to return can not, but alone weeping tears. Coupled with the poet's advanced age but humble official position, under the people, it is more sad. People can not return home, but the spring breeze has returned home, the poet can not help but envy the spring breeze. The poet sighs that he is in a foreign land, can only live with the mountain apes, and the river willows to enjoy the wind and smoke, like this, similar to Jia Yi's relegation to Changsha, I don't know how many more years before the end of the day?

This poem is not only about expressing nostalgia for the New Year. The poet compares himself to Jia Yi and expresses his indignation at what he has suffered.

Poem translator:

Kiang Kanghu