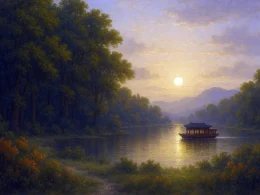

Down the blue mountain in the evening,

Moonl ight was my homeward escort .

Look ing back, I saw my path

Lie in levels of deep shadow...

I was passing the farm-house of a friend,

When his children called from a gate of thorn

And led me twining through j ade bamboos

Where green vines caught and held my clothes.

And I was glad of a chance to rest

And glad of a chance to drink with my friend.

We sang to the tune of the wind in the pines ;

And we finished our songs as the stars went down,

When, I being drunk and my friend more than happy,

Between us we forgot the world.

Original Poem

「下终南山过斛斯山人宿置酒」

李白

暮从碧山下,山月随人归。

却顾所来径,苍苍横翠微。

相携及田家,童稚开荆扉。

绿竹入幽径,青萝拂行衣。

欢言得所憩,美酒聊共挥。

长歌吟松风,曲尽河星稀。

我醉君复乐,陶然共忘机。

Interpretation

This poem was composed during Li Bai's tenure as a Hanlin academician in Chang'an (around 744 CE). Though close to the imperial court, he felt increasingly disillusioned with his thwarted ideals and grew weary of the constraints and hypocrisy of bureaucratic life. The night visit recorded in this poem is not merely a mountain stroll but a spiritual return from the court to the countryside, embodying his profound yearning for simple human connections and a free, natural way of life.

First Couplet: "暮从碧山下,山月随人归。"

Mù cóng bì shān xià, shān yuè suí rén guī.

At dusk, I descend the emerald mountain's height; The mountain moon follows me home through the night.

The opening paints a harmonious picture of human and nature in unity. "The mountain moon follows me home" personifies the moon with warmth—it is not merely a source of light but a tacit companion, suggesting the solace and companionship the poet finds after withdrawing from worldly noise.

Second Couplet: "却顾所来径,苍苍横翠微。"

Què gù suǒ lái jìng, cāngcāng héng cuìwēi.

Turning to gaze at the path I've trod, Vast azure mist veils the verdant sod.

The act of looking back is deeply meaningful. "The path I've trod" symbolizes the official career or worldly life he has just left, while the hazy beauty of "vast azure mist veiling verdant slopes" signifies that from a distance, past troubles are purified into transcendent beauty. This is both actual scenery and a reflection of inner transformation.

Third Couplet: "相携及田家,童稚开荆扉。"

Xiāng xié jí tiánjiā, tóngzhì kāi jīng fēi.

Hand in hand, we reach the farmer's gate; A child gladly opens the wicker door, elate.

"Wicker door" is a classic symbol of reclusive life. The detail of a child welcoming guests, free from formal etiquette, radiates natural warmth and trust, revealing an uncorrupted, simple human connection untouched by功利.

Fourth Couplet: "绿竹入幽径,青萝拂行衣。"

Lǜ zhú rù yōu jìng, qīng luó fú xíng yī.

Green bamboos lead down a secluded lane; Viridian vines brush our robes, easing strain.

These lines depict the hermit's surroundings with delicate detail. "Green bamboos" symbolize purity, while "viridian vines" exude rustic charm. The verbs "lead" and "brush" create亲切 interaction between scenery and travelers, making readers feel present in the serene, elegant environment.

Fifth Couplet: "欢言得所憩,美酒聊共挥。"

Huān yán dé suǒ qì, měijiǔ liáo gòng huī.

In happy talk, we find our proper rest; With fine wine, we drink our very best.

"Find our proper rest" refers not only to physical respite but to the soul finding归宿 in kindred spirits and nature. The verb "drink our best" vividly captures the unconstrained, spontaneous enthusiasm of drinking.

Sixth Couplet: "长歌吟松风,曲尽河星稀。"

Cháng gē yín sōng fēng, qǔ jìn hé xīng xī.

Singing long, our voices blend with pines' sigh; Songs end as river-stars sparse in the sky.

This couplet elevates joy to its peak. "Blend with pines' sigh" merges human song with natural sounds, embodying unity with nature. From dusk's arrival to "river-stars sparse," time's passage seems light and beautiful in merriment, suggesting hosts and guests reveling, oblivious to time.

Seventh Couplet: "我醉君复乐,陶然共忘机。"

Wǒ zuì jūn fù lè, táorán gòng wàng jī.

I'm drunk, you're joyful too, hearts set free; Intoxicated, we forget cunning, wild and carefree.

The conclusion reveals the poem's essence. "Forget cunning" derives from Zhuangzi, meaning discarding功利 and cunning to return to natural authenticity. This is not merely a post-drinking state but the highest life realm the poet seeks—achieving complete spiritual freedom and liberation through communion with kindred spirits and nature.

Holistic Appreciation

This poem documents a complete spiritual journey from "leaving the mundane" to "entering the world" (in another sense—immersing in simple life). Using time as the warp and movement as the weft, it progresses from descending the mountain, looking back, visiting, entering the path, joyful drinking, long singing, to intoxicated forgetting. Emotions evolve from serene joy to unrestrained transcendence. Li Bai elevates an ordinary night visit into an artistic representation of an ideal way of life, containing profound philosophical meaning and aesthetic pursuit within plain, conversational language.

Artistic Merits

- Pictorial Narrative Flow: Lines advance naturally with the poet’s footsteps and gaze, forming coherent, vivid tableaux that guide readers through the twilight mountain journey.

- Emotional Expression Blending Reality and Abstraction: The poem contains both realistic depictions like "green bamboos" and "viridian vines" and abstract expressions like "mountain moon follows" and "intoxicated forgetting"—real scenes evoke abstract feelings, which in turn illuminate the scenes, forming an integrated whole.

- Genuine Richness in Simplicity: The language is fresh and plain, unadorned, yet precisely captures scenic features and inner subtleties, achieving the artistic realm of "lotus rising from clear water, naturally unadorned."

Insights

In today’s world saturated with “strategizing minds” and relentless efficiency, this poem acts as a restorative elixir. It reminds us that genuine joy and peace are often found in sincere communion with kindred spirits and in silent dialogue with the natural world. What Li Bai calls “forgetting cunning” (忘机) is not passive withdrawal from society, but a conscious choice to embrace a more authentic, less utilitarian mode of being. It teaches us that alongside necessary striving, we should also preserve within ourselves a spiritual landscape—a realm where we can “sing long beneath sighing pines”—and there replenish our vitality and restore our capacity to perceive happiness.

Poem translator

Kiang Kanghu

About the poet

Li Bai (李白), 701 - 762 A.D., whose ancestral home was in Gansu, was preceded by Li Guang, a general of the Han Dynasty. Tang poetry is one of the brightest constellations in the history of Chinese literature, and one of the brightest stars is Li Bai.