While my little boat moves on its mooring of mist,

And daylight wanes, old memories begin...

How wide the world was, how close the trees to heaven,

And how clear in the water the nearness of the moon!

Original Poem

「宿建德江」

孟浩然

移舟泊烟渚,日暮客愁新。

野旷天低树,江清月近人。

Interpretation

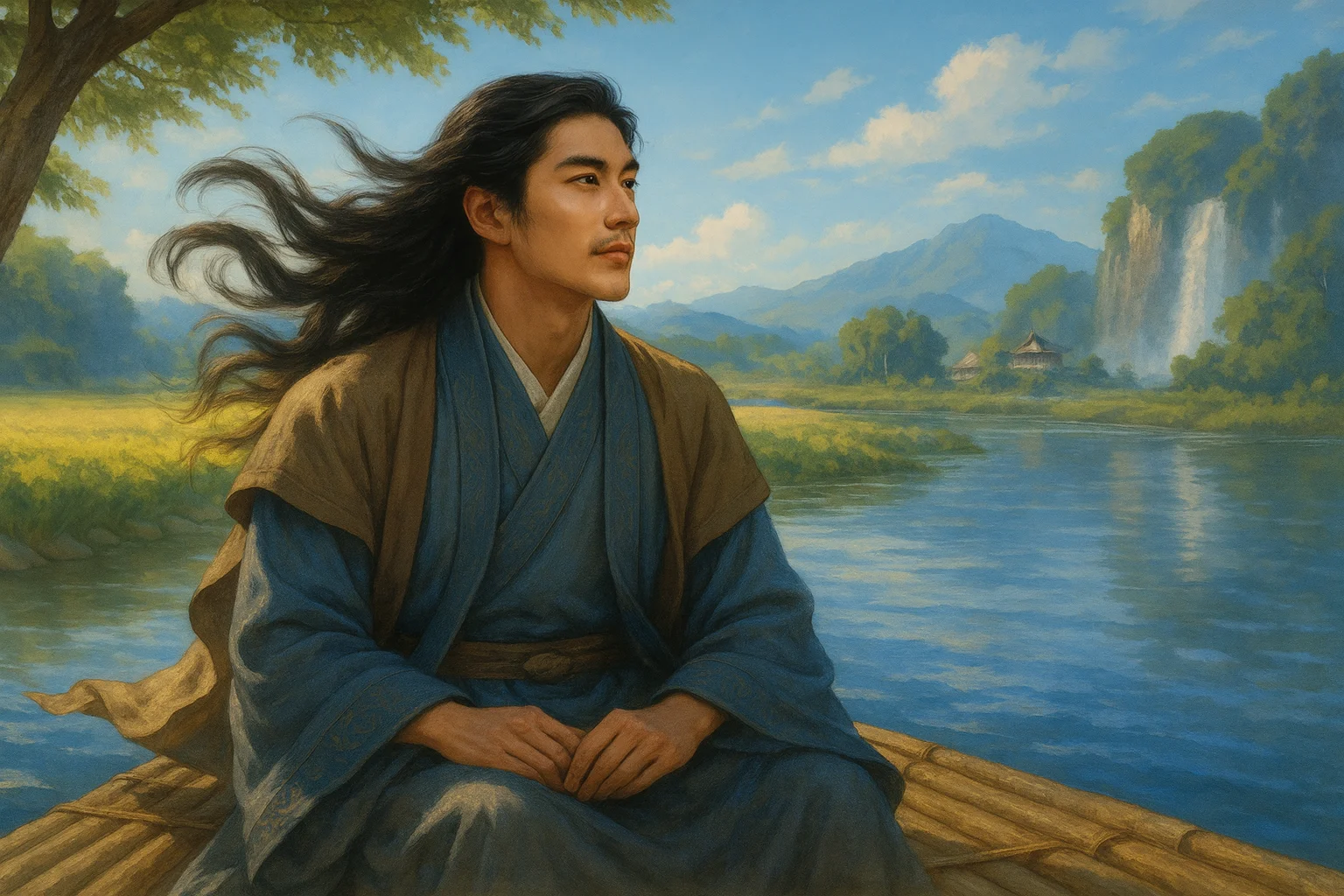

This poem was composed in the autumn of 730 AD, during Meng Haoran's wanderings through the Wu and Yue regions. Having failed the imperial examination in Chang'an the previous year, he wrote in resignation, "I've given up seeking office at the northern gate, / And retired to my humble hut by the Southern Hill." Determined to retire from public life, Meng Haoran, after returning to seclusion, chose instead to embark on a long journey. He left Xiangyang, sailed down the Han River into the Yangtze, passed through Xunyang and Jiande, journeying eastward all the way to central Yue. This was a self-imposed exile, a spiritual wandering—he sought to dilute the pain of his failure through geographical distance.

The River at Jiande refers to a section of the Xin'an River flowing through present-day Jiande County in Zhejiang. Here, the river is deep and clear, with dark, picturesque mountains lining its banks, a landscape once praised and immortalized by Southern Dynasty poets like Xie Lingyun and Shen Yue. However, when Meng Haoran moored his boat here, he had no heart to reminisce about past worthies. The word "mooring" in the title speaks volumes of a wanderer's constant state: no fixed destination, only one nightly mooring after another. His life, like this small boat, was being carried by the river of fate towards an unknown horizon.

First Couplet: "移舟泊烟渚,日暮客愁新。"

Yí zhōu bó yān zhǔ, rì mù kè chóu xīn.

My boat moves and moors by a mist-veiled sandbar. / As daylight fades, a traveler's sorrow stirs anew.

The opening narrates plainly, yet each word carries profound weight. "Moves and moors" is not a casual stop, but a conscious choice—before dusk falls, the poet seeks a place to spend the night. This action reveals the self-awareness of a wanderer: he knows the road ahead is long, and he must settle here tonight. The "mist-veiled sandbar" is shrouded in evening haze, misty and indistinct, seemingly there yet not. This image is both the actual scene before his eyes and an externalization of his state of mind: the poet's future, like this misty sandbar, is unclear, its direction indistinguishable. He moors here, not knowing where he will moor tomorrow.

"Dusk" is a classic trigger for sorrow in classical poetry. Yet, Meng Haoran does not say "a traveler's sorrow arises" or "a traveler's sorrow is born"; he says "a traveler's sorrow stirs anew." This word "anew" is the most poignant in the entire poem. It implies this is not his first time wandering, nor his first time feeling lonely at dusk. Sorrow has long existed; it's just that with each twilight, it returns, like the ebb and flow of tides, the cycle of seasons. He is not "giving birth" to sorrow; he is "claiming" the sorrow that already belongs to him.

Final Couplet: "野旷天低树,江清月近人。"

Yě kuàng tiān dī shù, jiāng qīng yuè jìn rén.

On boundless plains the sky stoops to the trees; / The river clear reflects the moon close and dear.

This couplet represents the pinnacle of scene-setting and emotion in Tang poetry, recited by countless people over centuries, yet its depths remain unfathomable. "On boundless plains the sky stoops to the trees" is a visual illusion, yet a psychological truth. With the vast wilderness offering no obstruction, the distant horizon naturally appears lower than the nearby treetops. This is a fact of physical perspective, but when Meng Haoran writes it, it carries a deeper meaning: when a person finds themselves within the immense expanse of heaven and earth, a sense of insignificance overwhelms everything. The sky is not truly lower; it is the poet who feels too small. The trees are not truly higher; it is the poet who has nothing to lean on. This line expresses the weightlessness and insignificance of a wanderer in a vast world.

Yet Meng Haoran does not let the poem sink into despair. Immediately, he writes, "The river clear reflects the moon close and dear." This is the poem's most tender miracle.

The clear river reflects the moon's shadow, making it seem within reach. The moon is a distant celestial body, yet due to the river's clarity, it becomes intimate. It is not the moon actively approaching the poet; it is the poet, because of the clear river, who can draw near to the moon. The word "close" signifies a shortening of physical distance and, more importantly, a dissolution of spiritual distance. On this unfamiliar river, in this lonely boat, within this boundless dusk and wilderness, he finally finds an existence willing to be near him. It is not a person, but the moon. But what of it? The moon is also a confidant.

Overall Appreciation

This is Meng Haoran's shortest poem, yet it presents the most holistic portrayal of his state of being. Twenty characters form an exceptionally clear structure: the first two lines describe human affairs—moving the boat, mooring, dusk, traveler's sorrow; the last two lines describe heaven and earth—boundless plains, low sky, trees, clear river, moon near. The first half is the wanderer's predicament; the second is nature's response. The first half is the separation between "I" and the world; the second is the reconciliation between "I" and the world. This reconciliation is not achieved by conquering loneliness, but by acknowledging loneliness, and then coexisting with it. The poet finds no old friend on the riverbank, receives no letter from home at the post station, returns to no hometown in his dreams. He merely sees the sky low, the moon near, and then writes these two lines on paper. After writing, he remains the traveler moored at the misty sandbar; tomorrow he will still sail east with the current. But at this moment, he is no longer facing heaven and earth alone—the moon is with him.

This poem can be read alongside "Mooring on the River at Tonglu, Sent to Old Friends in Guangling." On the night at Tonglu River, Meng Haoran sent two lines of tears to the far west of the sea, seeking solace outwardly. On the night at Jiande River, he turned his gaze back to the side of his boat, sitting facing the river moon, achieving self-sufficiency inwardly. The former is longing; the latter is Zen-like understanding. The former requires a distant "you"; the latter only requires a present "moon." From "sent to" to "near," from "distant" to "dear," it perfectly outlines the complete arc of Meng Haoran's inner healing during his wanderings.

Artistic Features

- Profound Depth Through Extreme Simplicity: Twenty characters exhaust four themes—wandering, loneliness, insignificance, and solace—with no redundant word, no forced effort. This is the ultimate realization of Meng Haoran's poetic ideal of "simple language with rich flavor."

- Psychological Portrayal of Visual Illusion: "The sky stoops to the trees" is not physical reality, but psychological truth—when a person feels insignificant, the world seems overwhelmingly oppressive. This subjectivized description of scenery makes the objective view a perfect projection of inner emotion.

- Emotional Weight of Verbs: "Moves" is the wanderer's active choice; "moors" is the traveler's temporary settling; "close" is the lonely one's sole comfort. Three verbs connect the emotional thread of the entire poem.

- Dual Spatial Contrast: The first two lines are close-up—boat, sandbar, person; the last two lines are distant view—plains, sky, trees, river, moon. Moving from near to far, then from far back to near (moon near person), it forms a complete visual cycle and an emotional resolution.

- The Suspended Beauty of the Closing Line: The poem concludes with "the moon close and dear," a state in progress, not an ending. The poet does not write "and so I was no longer sad," nor "and so I fell peacefully asleep." He merely records this moment of closeness and lets the verse hang there. The lingering charm is like the river moon, long-lasting.

Insights

This work teaches us: One can attain wholeness within loneliness; there is no need to wait for anyone to arrive. This is the greatest difference between Meng Haoran here and the self in "Mooring on the River at Tonglu, Sent to Old Friends in Guangling." On the night at Tonglu River, he was still sending tears, still longing, still hoping for an echo from afar; on the night at Jiande River, he sends out nothing, merely gazing quietly at the moon's reflection in the water, discovering it is so near. When facing loneliness, contemporary people habitually seek connection outwardly: making a call, sending a message, filling quiet nights with social networks. Meng Haoran offers another possibility: One can be without connection, yet not be lonely. When the river moon becomes a confidant, when the wilderness becomes a dwelling, when the solitary boat becomes a world—solitude is no longer deprivation, but abundance.

This poem holds an even deeper metaphor: the moon is the eternal other, yet also the most faithful companion. It does not question your past, does not plan your future, but merely sits with you on this night, at this moment, on this river. This is nature's gentlest gift to humanity: It solves no problems, but it is never absent from any predicament. For millennia, countless travelers have moored and spent the night on the River at Jiande; countless people have beheld the scene of "On boundless plains the sky stoops to the trees; / The river clear reflects the moon close and dear." Some among them might recall Meng Haoran's poem, some might not. But whether they recall the poem or not, the river and moonlight of that night will comfort every lonely traveler, just as they comforted Meng Haoran. For the moon is like that—it does not recognize poets, nor does it recognize commoners. It simply, equally, quietly, draws near to every person who looks down at the water.

Poem translator

Kiang Kanghu

About the poet

Meng Haoran (孟浩然), 689 - 740 AD, a native of Xiangyang, Hubei, was a famous poet of the Sheng Tang Dynasty. With the exception of one trip to the north when he was in his forties, when he was seeking fame in Chang'an and Luoyang, he spent most of his life in seclusion in his hometown of Lumenshan or roaming around.