Oh, but it is high and very dangerous!

Such travelling is harder than scaling the blue sky.

...Until two rulers of this region

Pushed their way through in the misty ages,

Forty-eight thousand years had passed

With nobody arriving across the Ch'in border.

And the Great White Mountain, westward, still has only a bird's path

Up to the summit of O-mei Peak -

Which was broken once by an earthquake and there were brave men lost,

Just finishing the stone rungs of their ladder toward heaven.

...High, as on a tall flag, six dragons drive the sun,

While the river, far below, lashes its twisted course.

Such height would be hard going for even a yellow crane,

So pity the poor monkeys who have only paws to use.

The Mountain of Green Clay is formed of many circles -

Each hundred steps, we have to turn nine turns among its mounds.

Panting, we brush Orion and pass the Well Star,

Then, holding our chests with our hands and sinking to the ground with a groan,

We wonder if this westward trail will never have an end.

The formidable path ahead grows darker, darker still,

With nothing heard but the call of birds hemmed in by the ancient forest,

Male birds smoothly wheeling, following the females;

And there come to us the melancholy voices of the cuckoos

Out on the empty mountain, under the lonely moon

Such travelling is harder than scaling the blue sky.

Even to hear of it turns the cheek pale,

With the highest crag barely a foot below heaven.

Dry pines hang, head down, from the face of the cliffs,

And a thousand plunging cataracts outroar one another

And send through ten thousand valleys a thunder of spinning stones.

With all this danger upon danger,

Why do people come here who live at a safe distance?

...Though Dagger-Tower Pass be firm and grim,

And while one man guards it

Ten thousand cannot force it,

What if he be not loyal,

But a wolf toward his fellows?

...There are ravenous tigers to fear in the day

And venomous reptiles in the night

With their teeth and their fangs ready

To cut people down like hemp .

...Though the City of Silk be delectable, I would rather turn home quickly.

Such travelling is harder than scaling the blue sky

But I still face westward with a dreary moan.

Original Poem

「蜀道难」

李白

噫吁嚱,危乎高哉!

蜀道之难,难于上青天!

蚕丛及鱼凫,开国何茫然!

尔来四万八千岁,不与秦塞通人烟。

西当太白有鸟道,可以横绝峨眉巅。

地崩山摧壮士死,然后天梯石栈相钩连。

上有六龙回日之高标,下有冲波逆折之回川。

黄鹤之飞尚不得过,猿猱欲度愁攀援。

青泥何盘盘,百步九折萦岩峦。

扪参历井仰胁息,以手抚膺坐长叹。

问君西游何时还?畏途巉岩不可攀。

但见悲鸟号古木,雄飞雌从绕林间。

又闻子规啼夜月,愁空山。

蜀道之难,难于上青天,使人听此凋朱颜!

连峰去天不盈尺,枯松倒挂倚绝壁。

飞湍瀑流争喧豗,砯崖转石万壑雷。

其险也如此,嗟尔远道之人胡为乎来哉!

剑阁峥嵘而崔嵬,一夫当关,万夫莫开。

所守或匪亲,化为狼与豺。

朝避猛虎,夕避长蛇,磨牙吮血,杀人如麻。

锦城虽云乐,不如早还家。

蜀道之难,难于上青天,侧身西望长咨嗟!

Interpretation

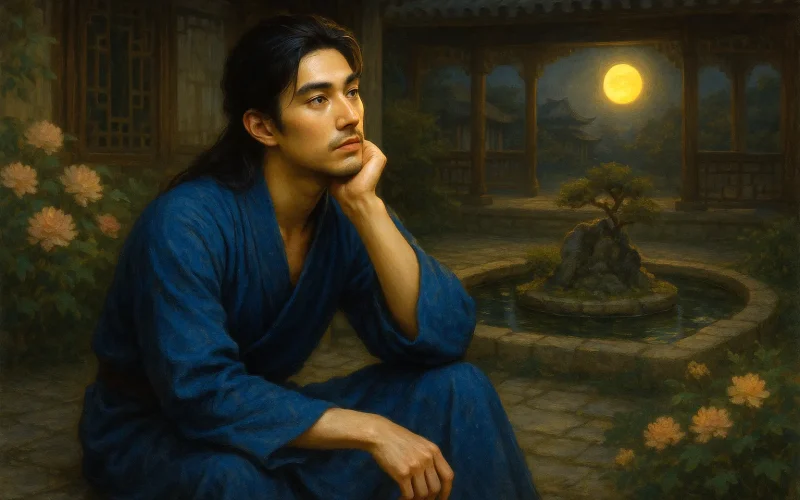

Composed around 742 CE during Li Bai's stay in Chang'an, this poem was written when the poet, despite his literary fame and appointment as a Hanlin Academician, faced profound conflict between his political ideals of "aiding common people and stabilizing the nation" and the reality of being a literary attendant. Experiencing officialdom's dangers and the court's political atmosphere firsthand, Li Bai created this work that, while depicting Sichuan's perilous paths, transcends mere landscape description to incorporate deep insights into political life and concerns for the nation's future, representing the pinnacle of his romanticist poetry.

First Stanza: "噫吁嚱,危乎高哉!蜀道之难,难于上青天!蚕丛及鱼凫,开国何茫然!尔来四万八千岁,不与秦塞通人烟。西当太白有鸟道,可以横绝峨眉巅。地崩山摧壮士死,然后天梯石栈相钩连。"

Yī xū xī, wēi hū gāo zāi! Shǔ dào zhī nán, nán yú shàng qīngtiān! Cán cóng jí yú fú, kāiguó hé mángrán! Ěr lái sìwàn bāqiān suì, bù yǔ qín sāi tōng rényān. Xī dāng Tàibái yǒu niǎo dào, kěyǐ héng jué Éméi diān. Dì bēng shān cuī zhuàngshì sǐ, ránhòu tiāntī shízhàn xiāng gōu lián.

Ah! How perilous, how high! The road to Shu's harder than climbing the sky! Since Can Cong and Yu Fu founded the state, Forty-eight thousand years have passed, remote and late. No contact with Qin's land, no human trace, Only bird paths cross Great White's rocky face, Reaching to Emei's summit, a dangerous place. Then mountains crumbled, heroes died in the strife, Before sky-ladders and stone paths came to life.

The poem opens with thunderous exclamation, establishing its majestic tone. Through mythological legends and extreme exaggeration of time (48,000 years) and space (bird paths), the poet places the road to Shu in a mysterious, ancient context, endowing it with insurmountable grandeur and historical weight. The "Five Heroes' Mountain Splitting" legend adds tragic cost to the road's creation.

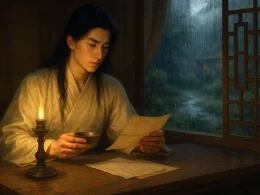

Second Stanza: "上有六龙回日之高标,下有冲波逆折之回川。黄鹤之飞尚不得过,猿猱欲度愁攀援。青泥何盘盘,百步九折萦岩峦。扪参历井仰胁息,以手抚膺坐长叹。问君西游何时还?畏途巉岩不可攀。但见悲鸟号古木,雄飞雌从绕林间。又闻子规啼夜月,愁空山。蜀道之难,难于上青天,使人听此凋朱颜!"

Shàng yǒu liù lóng huí rì zhī gāo biāo, xià yǒu chōng bō nì zhé zhī huí chuān. Huáng hè zhī fēi shàng bù dé guò, yuán náo yù dù chóu pānyuán. Qīng ní hé pán pán, bǎi bù jiǔ zhé yíng yán luán. Mén shēn lì jǐng yǎng xié xī, yǐ shǒu fǔ yīng zuò cháng tàn. Wèn jūn xī yóu hé shí huán? Wèi tú chán yán bùkě pān. Dàn jiàn bēi niǎo hào gǔ mù, xióng fēi cí cóng rào lín jiān. Yòu wén zǐguī tí yè yuè, chóu kōng shān. Shǔ dào zhī nán, nán yú shàng qīngtiān, shǐ rén tīng cǐ diāo zhū yán!

Above, peaks make sun's dragon steeds retreat; Below, torrents whirl in defeat. Yellow cranes cannot fly across this zone; Even apes fear to climb these heights of stone. Blue Mud Trail winds round cliffs nine turns per hundred paces; We touch stars, gasp breath, hands on hearts, making grimaces. I ask, friend journeying west, when will you return? These dreaded crags make courage burn! Sad birds cry on ancient trees, Males-follow-females flit through the breeze. Then cuckoos sing beneath moon's light, Filling empty hills with sorrow's night. The road to Shu's harder than climbing the sky— Hearing this, one's rosy face will die!

This section exhaustively depicts the road's difficulty from multiple dimensions. "Six dragons make the sun retreat" and "whirling torrents" create vertical extremes; "yellow cranes" and "apes" provide animal-world contrast to its height; "touching stars" uses constellations for dizzying exaggeration. The introduction of "sad birds" and "cuckoos" (whose cry sounds like "better go home") creates an auditory atmosphere of bleakness and sorrow, perfectly merging natural danger with psychological fear.

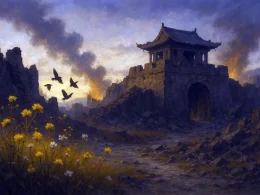

Third Stanza: "连峰去天不盈尺,枯松倒挂倚绝壁。飞湍瀑流争喧豗,砯崖转石万壑雷。其险也如此,嗟尔远道之人胡为乎来哉!"

Lián fēng qù tiān bù yíng chǐ, kū sōng dào guà yǐ juébì. Fēi tuān pù liú zhēng xuān huī, pīng yá zhuǎn shí wàn hè léi. Qí xiǎn yě rú cǐ, jiē ěr yuǎndào zhī rén hú wéi hū lái zāi!

Peaks almost scrape the sky, not a foot away; Withered pines cling to cliffs, upside-down they sway. Waterfalls compete in roaring noise, Crashing on rocks like thunder's voice. Since such perils here are found, Why has your distant feet this pathway bound?

Here the poet intensifies visual and auditory oppression to the extreme. "Peaks almost scrape the sky" exaggerates height; "thunder in ten thousand valleys" magnifies sound. Facing this breathtaking landscape, the poet's direct questioning shows concern for adventurers while implicitly warning those seeking fame in dangerous officialdom.

Fourth Stanza: "剑阁峥嵘而崔嵬,一夫当关,万夫莫开。所守或匪亲,化为狼与豺。朝避猛虎,夕避长蛇,磨牙吮血,杀人如麻。锦城虽云乐,不如早还家。蜀道之难,难于上青天,侧身西望长咨嗟!"

Jiàn gé zhēngróng ér cuīwéi, yī fū dāng guān, wàn fū mò kāi. Suǒ shǒu huò fěi qīn, huà wéi láng yǔ chái. Zhāo bì měnghǔ, xī bì cháng shé, mó yá shǔn xuè, shā rén rú má. Jǐn chéng suī yún lè, bùrú zǎo huán jiā. Shǔ dào zhī nán, nán yú shàng qīngtiān, cèshēn xī wàng cháng zī jiē!

Jian'ge Pass towers steep and grand; One man can guard it, none invade the land. But if disloyal men this fortress hold, They turn to wolves, cruel and bold. Dodge tigers at dawn, snakes at night, Teeth sharpened, blood-sucking, killing outright. Though Brocade City's pleasures are sung, Better go home, while you're still young! The road to Shu's harder than climbing the sky— I turn west, heaving sighs long and high!

The poem's meaning becomes clear here—transitioning from natural danger to social and political peril. The impregnable Jian'ge Pass, if held by untrustworthy men, becomes a source of disaster. "Tigers" and "snakes" refer both to real beasts and metaphorically represent political dangers and dark officialdom. The final advice "better go home early" echoes the opening exclamation, revealing the theme: both the natural road to Shu and life's "official path" contain unpredictable dangers requiring constant vigilance.

Holistic Appreciation

With astonishing imaginative power, the poet elevates an old Music Bureau theme to its zenith. Centering on "difficulty," the poem develops chronologically from ancient to modern, macro to micro, nature to human affairs. Emotion progresses from awe to sorrow, then to warning, finally culminating in profound sighs, creating surging emotional waves. The triple refrain "The road to Shu's harder than climbing the sky" acts as a musical motif, structuring the poem with intensifying emotion. It is both a ode and elegy to Sichuan's landscape, and Li Bai's tragic allegory for his era and personal fate.

Artistic Merits

- Fantastical Imagination, Extraordinary Exaggeration: Blending history, astronomy, and landscape into a magnificent artistic realm.

- Varied Techniques, Irregular Meter: Unrestrained language with prose-like lines creates urgent rhythm matching the road's danger and emotional turbulence.

- Scene-Embedded Emotion, Profound Meaning: Throughout landscape description carries deep feeling, seamlessly integrating political insight and national concern into the depiction of Sichuan's perils, achieving romanticism-realism unity.

Insights

This eternally captivating work teaches us that truly great poetry must transcend concrete description to symbolize universal human dilemmas. The towering "road to Shu" represents challenges, obstacles, or fears faced by any generation. While emphasizing its "difficulty," Li Bai's overflowing talent showcases the boundless imagination and indomitable spirit humans can summon against adversity. It is both warning and ode—praising the extraordinary courage and wisdom humanity demonstrates in understanding and challenging limits.

Poem translator

Kiang Kanghu

About the poet

Li Bai (李白), 701 - 762 A.D., whose ancestral home was in Gansu, was preceded by Li Guang, a general of the Han Dynasty. Tang poetry is one of the brightest constellations in the history of Chinese literature, and one of the brightest stars is Li Bai.