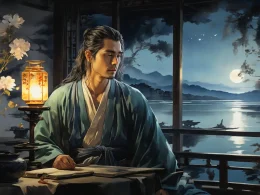

Her candle-light is silvery on her chill bright screen.

Her little silk fan is for fireflies....

She lies watching her staircase cold in the moon,

And two stars parted by the River of Heaven.

Original Poem

「秋夕」

杜牧

银烛秋光冷画屏,轻罗小扇扑流萤。

天阶夜色凉如水,坐看牵牛织女星。

Interpretation

While the precise date of this poem's composition remains uncertain, its subtle artistry and compassionate depth identify it as a mature work born from Du Mu's profound observation of the destinies of women and life within the imperial palace. The Tang imperial palace was vast, often housing tens of thousands of palace women, the great majority of whom would exhaust their youth and lives within its deep walls and high enclosures, forming a hidden wound beneath the empire's glorious exterior. Although Du Mu never served extensively within the palace himself, his insight into the cycles of history and his concern for individual fate enabled him to look beyond those walls, perceiving with a poet's heart the silent joys and sorrows contained within.

This poem does not address a specific individual but rather presents a typified portrayal and poetic sublimation of the tragic fate shared by palace women as a collective. The poet chooses the "autumn night"—a seasonal moment associated with reunion and warmth—to starkly contrast the profound loneliness and desolation inherent to life deep within the palace. The scene masterfully blends meticulous realistic detail (the chilled painted screen, catching fireflies) with profound symbolic resonance (the autumn fan, the Milky Way), allowing these brief four lines to function both as a hauntingly beautiful nocturne of palace life and as a timeless allegory concerning confinement, the passage of time, and elusive longing. Its poignant beauty and emotional power remain undiminished across the centuries.

First Couplet: 银烛秋光冷画屏,轻罗小扇扑流萤。

Yín zhú qiū guāng lěng huà píng, qīng luó xiǎo shàn pū liú yíng.

Silver candles, autumn moonlight, chill the painted screen; Her silken fan for fireflies caught in flight is keen.

The opening lines immediately establish an atmosphere of solitude and chill through starkly contrasted imagery. "Silver candles" and "autumn moonlight" are sources of light, yet their combined effect upon the "painted screen" produces a sensation of "chill." This represents a synaesthetic shift from the visual to the tactile, and simultaneously externalizes the figure's inner desolation. The ornate "painted screen," in this context, fails to provide warmth; instead, its stillness and exquisite craftsmanship accentuate the emptiness of the surroundings and the solitude of the occupant's heart. The second line introduces subtle movement with the dynamic detail of "catching fireflies." Fireflies typically thrive in wild, grassy areas; their presence within the deep palace implies the neglect and wild growth in some corners of the grounds. The "silken fan" is an object for summer cooling, useless in autumn, echoing the classical metaphor of the "autumn fan cast aside," which symbolizes the palace lady's fate of being forgotten and neglected by the emperor. Her act of catching fireflies serves both to pass the long, tedious night and, perhaps unconsciously, mirrors her own fate—as fleeting, adrift, and destined to vanish into darkness as the fireflies themselves.

Final Couplet: 天阶夜色凉如水,坐看牵牛织女星。

Tiān jiē yè sè liáng rú shuǐ, zuò kàn Qiānniú Zhīnǚ xīng.

The palace steps are steeped in night, cold as water pure; She sits to watch the Herd-boy star and Weaving Maid secure.

Time passes, the night deepens, and the scene shifts from indoors to outdoors. "The palace steps" refer to the stairs of the palace complex, indicating her location at the very heart of power and ritual. Yet, the simile "cold as water pure" reinforces the chill in her soul with a tangible, physical sensation. This "coldness" is pervasive, inescapable, much like her fate. Within this boundless chill, her final action is "sits to watch." The word "sits" captures her posture—one of protracted, silent, and deeply absorbed contemplation. Her gaze is fixed upon "the Herd-boy star and Weaving Maid"—the stars Altair and Vega. Their legend symbolizes love separated yet enduring, and a brief annual reunion. The palace lady's gaze contains multiple layers of meaning: a profound yearning for genuine affection; a painful awareness of her own plight, denied even such a yearly meeting; envy for the love and freedom celebrated in the myth; and infinite sorrow for her own fate of being eternally confined upon the "palace steps," capable only of gazing upward at an unattainable ideal. This marks the poem's emotional climax: within this silent gaze surges the most profound sorrow and longing.

Holistic Appreciation

This heptasyllabic quatrain is a masterpiece among "palace plaint" poems. With utmost concision, it stages a psychological drama that moves from the exterior to the interior, from action to stillness, culminating in a gaze toward the infinite starry sky.

The poem unfolds with nuanced emotional logic: the first line establishes the environmental "chill," the physical embodiment of loneliness. The second line depicts the figure's "motion," a futile attempt to dispel that solitude. The third line deepens the environmental "cold," representing the all-encompassing nature of loneliness once it proves inescapable. The final line presents the figure's "stillness" and "gaze," the act of, after acknowledging and enduring this loneliness and desolation, projecting her entire being onto a distant, unreachable symbol, entering a state of silent, meditative sorrow and reverie.

Du Mu's brilliance lies in the fact that not a single word directly voices "complaint." Yet, through a series of meticulously chosen images and details—"chill," "cold," "autumn fan," "fireflies," "sits to watch"—he expresses with profound subtlety and penetrating force the deep anguish of palace women: forgotten by time, isolated from splendor, with emotions adrift. Particularly in the final line, placing the individual tragedy against the mythological backdrop of the vast cosmos grants the personal lament a quality of eternity and sublimity connected to universal time and space, creating resonance that lingers endlessly.

Artistic Merits

- Metaphorical Weaving of an Imagistic System: The poem's images are not randomly assembled but form an interconnected metaphorical system. "Silver candles" and the "painted screen" symbolize the gorgeous yet hollow shell of palace life; the "silken fan" serves as a metaphor for the figure's own fate (the cast-aside autumn fan); "fireflies" suggest environmental neglect and the fragility of life; the "palace steps" represent insurmountable hierarchy and rigid order; and the "Herd-boy and Weaving Maid stars" function as a contrasting ideal realm. Together, these images construct a hermetically sealed world rich in symbolic meaning, precisely conveying the palace lady's circumstances and state of mind.

- An Emotional Thread Woven Through Sensations of Temperature: The poem begins with "chill" and continues with "cold," forming a clear emotional thread defined by temperature. The progression from the "chill" of indoor objects to the "cold" of the outdoor night is not merely descriptive but is the poetic externalization of the character's inner world sinking step by step into desolate isolation. The sustained use of this synaesthetic technique enhances the poem's evocative power.

- Rhythm and Tension Through the Juxtaposition of Motion and Stillness: The first couplet contains the stillness of light and shadow (the chilled screen) and the motion of person and insect (catching fireflies); the second couplet contains the stillness of the enveloping night (cold as water) and the stillness of the upward gaze (sits to watch). This subtle dynamism and immense inner turbulence contained within an overall quiet tonal base creates the poem's internal tension, rendering the scene still yet alive, the emotion restrained yet intensely potent.

- Deepening and Contrast Through Mythological Allusion: The use of the "Herd-boy and Weaving Maid stars" is the masterstroke that illuminates the whole. It is not merely a simple allusion for conveying sentiment but establishes a poignant contrast: the separation in the myth allows for an annual crossing, while the separation within the deep palace is boundless and hopeless. This elevates the poem's pathos beyond specific grievance to touch upon the universal human longing for freedom, love, and belonging, and the eternal predicament of its frustration.

Insights

This exquisite poem acts as a mirror transcending time, reflecting the universal lament of constrained lives. It teaches us that the deepest solitude often resides not in the wilderness but within the most ornate cages; the most fervent longings are often projected upon the most distant, most unattainable symbols.

The tragedy of the palace lady lies not only in the absence of love but, more fundamentally, in the comprehensive stifling of her emotions, will, and vitality as a complete person within an institutionalized environment. Her idle act of catching fireflies is the aimless expenditure of her remaining vitality; her silent posture of stargazing represents her spirit's sole anchor to the only visible "beyond." This enlightens us that any environment that disregards the emotional needs and spiritual freedom of the individual, regardless of its external magnificence, is intrinsically cold.

Simultaneously, the poem demonstrates how art gives form to inexpressible suffering. Du Mu renders loneliness palpable through the "chilled painted screen" and the "night cold as water," and makes sorrow visible through "catching fireflies" and "sitting to watch the stars." It reminds us that when facing those indescribable sensations of "cold" and "solitude" in our own lives or the lives of others, we might seek or create our own "poetry"—a form of beauty capable of bearing, expressing, and thereby provisionally settling those emotions. Within this form, the seemingly insignificant joys and sorrows of the individual can connect with the autumn light, the night, and the Milky Way, giving rise, within absolute solitude, to a hauntingly beautiful dignity that is inherently human.

Poem translator

Kiang Kanghu

About the poet

Du Mu (杜牧), 803 - 853 AD, was a native of Xi'an, Shaanxi Province. Among the poets of the Late Tang Dynasty, he was one of those who had his own characteristics, and later people called Li Shangyin and Du Mu as "Little Li and Du". His poems are bright and colorful.