Doors locked, curtains drawn down, on the mossy ground,

In winding corridor alone I stroll around.

By lunar halo the rising wind is foretold.

How can the flowers bloom when drenched in dew cold?

I toss in bed when curtain's hit by a bat;

I am surprised to hear in the net squeak a rat.

Alone I talk with your shadow by the lamplight.

How can I help singing with you "Rising at Night"?

Original Poem

「正月崇让宅」

李商隐

密锁重关掩绿苔,廊深阁迥此徘徊。

先知风起月含晕,尚自露寒花未开。

蝙拂帘旌终展转,鼠翻窗网小惊猜。

背灯独共馀香语,不觉犹歌起夜来。

Interpretation

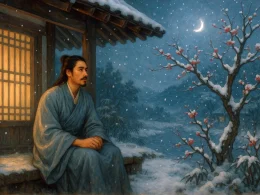

This poem represents the most profound in its perception of time and space, and the most haunting in its fusion of self and scene within Li Shangyin’s sequence of poems mourning his wife. Composed in the first lunar month, six years after the death of his wife, Lady Wang, the poet returns to the old estate of his father-in-law in the Chongrang quarter of Luoyang—a place once shared with his wife. The poem takes his solitary wandering through the desolate estate at midnight as its thread. Within the interweaving of enclosed space, suspended time, and a disoriented consciousness, it constructs a surreal domain where spirits linger, memories materialize, and grief erodes the bone, pushing the theme of mourning to an extreme realm where reality and illusion, mind and world, are indistinguishable.

First Couplet: 密锁重关掩绿苔,廊深阁迥此徘徊。

Mì suǒ chóng guān yǎn lǜ tái, láng shēn gé jiǒng cǐ pái huái.

Doors tight-locked, gates double-barred, green moss veils the ground;

Through deep arcades, past distant towers, I wander, pacing round.

Explication: The opening uses the lockdown and desolation of physical space to give form to the inner world’s confinement and barrenness. "Doors tight-locked, gates double-barred" signifies isolation from the outside world, a forced closure of the gates to the past; "green moss veils the ground" is the silent evidence of time’s erosion, declaring the passing of people and events. "Deep arcades… distant towers" describes not only the architecture’s depth but also metaphors for the long passageways of memory and the endless search of the spirit; "I wander, pacing round" depicts the poet drifting through the ruins of time like a lone ghost, establishing the poem’s eerie tone of desolation.

Second Couplet: 先知风起月含晕,尚自露寒花未开。

Xiān zhī fēng qǐ yuè hán yūn, shàng zì lù hán huā wèi kāi.

First knowing wind will rise—the haloed moon foretells;

Still, in the cold, dew-laden air, the flowers wait in their buds.

Explication: The gaze shifts from inside the house to the courtyard, capturing subtle portents in nature, all refracted through the sorrowful lens of his heart. "The haloed moon" is a celestial sign of impending wind and rain, here becoming the visual externalization of inner turmoil and tear-blurred eyes; "the flowers wait in their buds" aligns with the season (the first month) but, more importantly, serves as a symbol of congealed emotion and arrested hope—spring has come, yet warmth remains distant, just as his wife is forever gone, and joy will never return. With a seer’s sensitivity, the poet interprets all natural phenomena as omens of sorrow.

Third Couplet: 蝙拂帘旌终展转,鼠翻窗网小惊猜。

Biān fú lián jīng zhōng zhǎn zhuǎn, shǔ fān chuāng wǎng xiǎo jīng cāi.

A bat brushes the curtain’s fringe—I toss till night is spent;

A rat rustles the window screen—a small shock, a suspicion sent.

Explication: Moving from macro vistas to micro sounds, heightened auditory and tactile senses point to extreme nervous tension and fragility. "A bat brushes the curtain’s fringe," "A rat rustles the window screen"—these are the only faint sounds breaking the deathly silence of the abandoned estate, yet amplified infinitely by the lonely poet. "I toss till night is spent" describes the physical torment of a sleepless night; "a small shock, a suspicion sent" depicts psychological suffering rife with fear and conjecture—this "suspicion" is not merely about the source of the sounds but, deeper, a faint, subconscious hope that the disturbance might be the return of the departed soul, followed by even deeper despair. The small intrusions of creatures become stones cast into the lake of his heart, stirring great waves of grief.

Final Couplet: 背灯独共馀香语,不觉犹歌起夜来。

Bèi dēng dú gòng yú xiāng yǔ, bù jué yóu gē Qǐ Yè Lái.

My back to the lamp, alone, I whisper to a lingering scent;

Unaware, I find myself singing the old song, "Rising at Night."

Explication: This couplet is the emotional and artistic pinnacle of the poem, reaching a trance-like state of a disintegrated spirit. "My back to the lamp" is a posture of turning away from the light (reality) toward darkness (memory and illusion); "a lingering scent" is an olfactory phantom, the last and most elusive trace of the departed’s presence; "whisper to" accomplishes the leap from soliloquy to imagined dialogue, a splitting and compensation of the self in absolute solitude. The final line, "Unaware, I find myself singing the old song, 'Rising at Night,'" is the most heart-wrenching: "Rising at Night" is an old yuefu title, often expressing a woman’s longing for her husband. In his delirium, the poet unconsciously assumes his wife’s role, singing her old song. This is the ultimate transposition and inversion of identity in extreme grief—he not only misses her but, in illusion, becomes her, speaking for her the longing she should have felt for him, the one left alive. This is one of the most extraordinary and tragic techniques in the history of mourning poetry.

Holistic Appreciation

This is a "poem of spirit-summoning" that takes space as its shrine, time as its offering, and the senses as its passageway. The poem’s structure unfolds as a "sensory pilgrimage" through a mansion at midnight: sight (green moss, haloed moon), touch (cold dew), hearing (bat’s brush, rat’s rustle), and smell (lingering scent) are intensely activated in turn, yet all point inward to disillusion and grief. Each sensory experience becomes a key that unlocks floodgates of memory and pricks the nerves of the present, culminating in the self-produced sound of "singing… 'Rising at Night,'" achieving a complete dissolution of boundaries between self and other, living and dead, memory and reality.

Li Shangyin’s ultimate achievement lies in immersing the pain of mourning completely within a sleepwalking, on-site experience. The "I" in the poem is not calmly reminiscing but actively reliving that space and moment of utter loss. Every detail of the desolate estate (locks, moss, arcades, towers, curtain, window, lamp) is not merely background but participates in constructing the sorrow, or even becomes the material form of sorrow itself. The boundary between poet and environment is so blurred that he seems to have become the estate’s ghost, and the estate has become the ruins of his soul. This writing method, where object and self share the grief, and mind and scene unite, gives the sorrow a pervasive, oppressive physicality.

Artistic Merits

- The Suffocating Poetics of Enclosed Space: The poem’s imagery is intensely concentrated within the closed system of the "estate" (locks, gates, arcades, towers, curtain, window, lamp), creating a sense of inescapable suffocation and a coffin-like stagnation of time and space—the perfect vessel for imprisoning sorrow and memory.

- Sensory Narrative Leading to Hallucination: The poetic narrative strictly follows the sequence of sensory discovery, yet each piece of sensory information leads to an inner tragic scene, ultimately thoroughly blurring the line between objective perception and subjective hallucination, as with the uncertain existence of the "lingering scent" or the conscious intent behind "singing… 'Rising at Night.'"

- The Subtlety of Verbs and the Development of Psyche: Verbs like "veils," "pacing round," "foretells," "brushes," "rustles," "shock… suspicion," "back to," "whisper to," and "singing" precisely depict the process of the external environment’s decay and the subtle tremors of the inner heart. Particularly, the virtual nature of "whisper to" and the unconsciousness of "singing" reach directly to the subconscious level.

- Self-Referential Allusion and Emotional Reversal: The allusion to "Rising at Night" in the final line is not for scholarly display but achieves an uncanny substitution of the emotional subject, letting the poet "become" the mourned one, thereby deepening the one-directional longing into a two-way, cyclical, inescapable vortex of sorrow.

Insights

This work is like a labyrinth of memory and an altar of mourning built with verse, showing how loss can imprison a person in a spatiotemporal cage constructed from the details of the past. It reveals that the deepest grief often manifests as a morbid sensitivity to and dependence on specific spaces and sensory traces, even leading to hallucinatory dialogues like "whisper to a lingering scent" and confused identity like "singing… 'Rising at Night.'"

From a psychological perspective, this poem can be seen as a precious literary record of complex grief. It reminds us that true remembrance may involve not just sorrow but entering a state of deep entanglement with memory and environment, a temporary disintegration of the sense of reality. This has referential value for understanding and processing profound experiences of loss. Simultaneously, the poem demonstrates the power of art as a form of "spirit-summoning"—through an intensely personal, sensory system of symbols (green moss, haloed moon, lingering scent, old song), Li Shangyin attempts to summon and solidify the irrevocably departed and the lost time, granting them a poignant eternity within the text.

Li Shangyin’s Chongrang Estate is not just an old mansion in a corner of Luoyang; it is a ruin of memory and a shrine of mourning that any soul who has experienced profound loss might enter. There, he accomplished not only a memorial to his wife but also a solitary and magnificent poetic survey of the eternal confrontation between presence and absence.

Poem translator

Xu Yuanchong (许渊冲)

About the poet

Li Shangyin (李商隐), 813 - 858 AD, was a great poet of the late Tang Dynasty. His poems were on a par with those of Du Mu, and he was known as "Little Li Du". Li Shangyin was a native of Qinyang, Jiaozuo City, Henan Province. When he was a teenager, he lost his father at the age of nine, and was called "Zheshui East and West, half a century of wandering".