While worldly matters take their turn,

Ancient, modern, to and fro,

Rivers and mountains are changeless in their glory

And still to be witnessed from this trail.

Where a fisher-boat dips by a waterfall,

Where the air grows colder, deep in the valley,

The monument of Yang remains;

And we have wept, reading the words.

Original Poem

「与诸子登岘山」

孟浩然

人事有代谢,往来成古今。

江山留胜迹,我辈复登临。

水落鱼梁浅,天寒梦泽深。

羊公碑字在,读罢泪沾襟。

Interpretation

This poem was composed around 732 CE, during Meng Haoran's period of reclusion in Xiangyang. Mount Xian, located south of Xiangyang city, was a scenic spot frequented by local scholars and commoners for outings. It held particular spiritual weight due to its association with the famous Western Jin dynasty general, Yang Hu. While defending Xiangyang, Yang Hu, known for his approachable and benevolent governance, won the people's hearts. He often climbed Mount Xian and once sighed to his companions: "Since the universe came into being, this mountain has existed. How many worthies and outstanding men, like you and me, have climbed it to gaze into the distance! All have vanished into obscurity, which grieves me deeply." After his death, the people of Xiangyang erected a stele and built a temple on Mount Xian in his honor, offering sacrifices seasonally. Those who looked upon his stele could not help but shed tears, so Du Yu named it the "Stele of Tears."

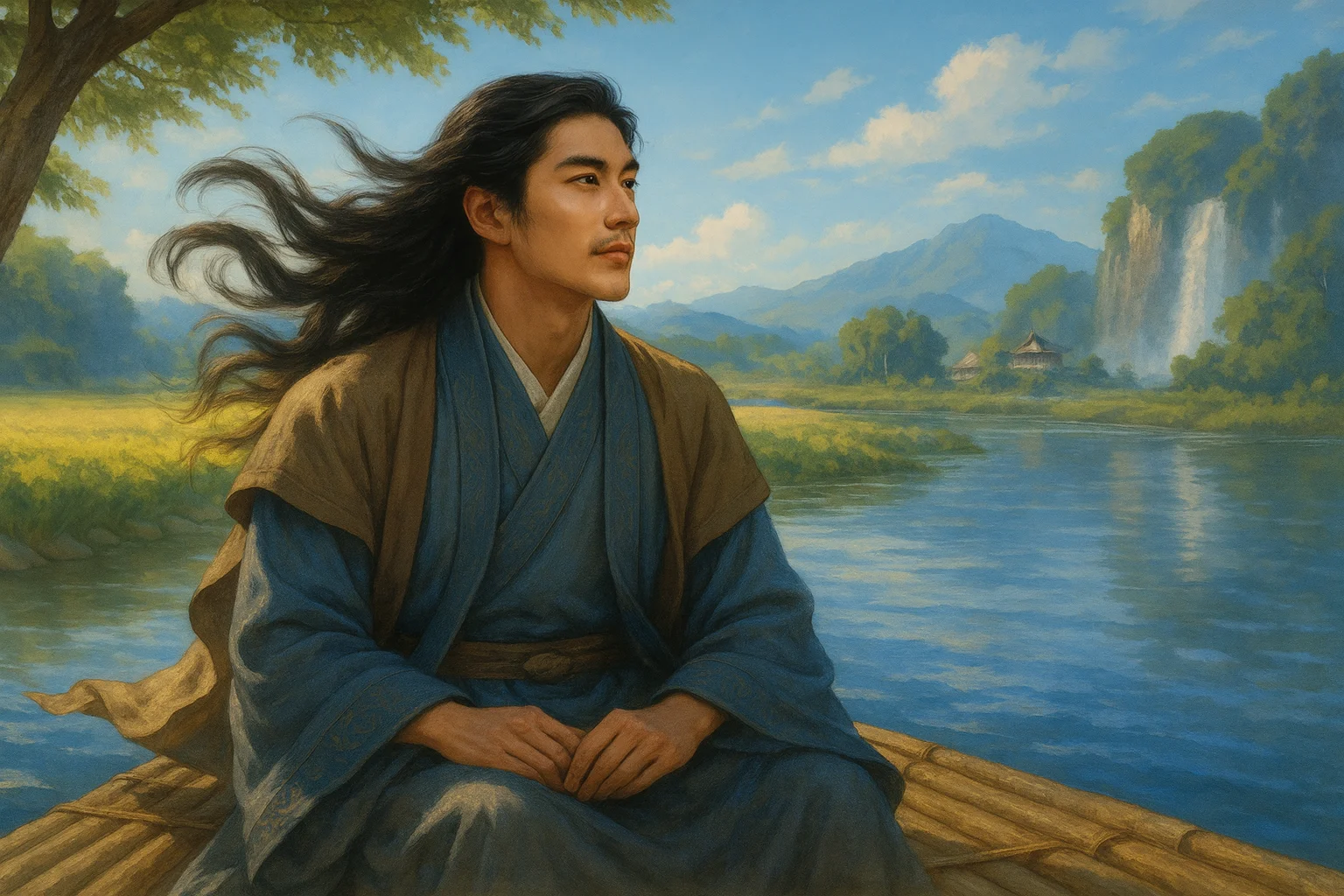

Meng Haoran spent most of his life in Xiangyang, and Mount Xian was a familiar place for his outings. However, by this time, he was past forty, having experienced the disappointment of seeking office in Chang'an, and had completely abandoned thoughts of an "official career," returning to a life of fields and gardens. When he and his friends climbed this hill again, a place that carried the echoes of Yang Hu, the stele's inscription was weathered, the mountain scenery remained, and the boundary between history and the present momentarily dissolved. Yang Hu had once worried about "vanishing into obscurity," yet ultimately achieved historical fame through his virtuous governance. Meng Haoran, however, whose ambition was to aid the world, grew old as a commoner, making even the worry about "obscurity" seem a luxury. This ascent was thus no ordinary excursion but became a dialogue across more than four centuries. The poet faced not a cold stone tablet, but a mirror of fate both similar to and vastly different from his own. The tears in the poem are half for Yang Hu, half for himself.

First Couplet: "人事有代谢,往来成古今。"

Rénshì yǒu dàixiè, wǎnglái chéng gǔjīn.

Human affairs forever wax and wane; / Coming and going, past and present form a chain.

The poem opens startlingly, without any scenic preface, beginning directly with reflection. This is extremely rare in Meng Haoran's poetry but precisely reveals his agitated state of mind. "Wax and wane" draws from the nature of creation itself—the flourishing and withering of plants, the rise and fall of dynasties, the birth and death of human life are all contained within. "Coming and going" refers to the passage and disappearance of countless individual lives through time. With the most economical language, the poet articulates a core proposition of historical philosophy: the ancient and the modern are not sharply separated but are layered accumulations of countless instances of "waxing and waning" and "coming and going." The place where he now stands was once stood upon by Yang Hu, by countless unknown others, and "our generation" is but another link in this long chain. This couplet suddenly elevates the personal feelings of the ascent to a universal contemplation of human destiny. Its vast perspective and profound gravity establish the poem's expansive, deep-toned foundation.

Second Couplet: "江山留胜迹,我辈复登临。"

Jiāngshān liú shèngjì, wǒ bèi fù dēnglín.

Rivers and hills keep vestiges of their prime; / Again we climb the hill at present time.

Following directly from "past and present," it contrasts the permanence of "rivers and hills" with the impermanence of "human affairs." The word "keep" carries immense weight—what makes a site historic is not its scenic beauty but the memory and virtuous legacy it bears. Yang Hu is gone, but the stele remains; this is the testimony the landscape "keeps" for the ancients. "Again we climb"—the word "again" incorporates the present climbers into the sequence of countless ascenders over thousands of years: Yang Hu climbed, Tang scholars climbed, and future visitors will climb. The poet's present existence is both a current reality and will become the "ancients" in the eyes of future generations. This couplet delves into the dimension of time more concretely and poignantly than the first: we are merely repeating the actions of the ancients, repeating their sentiments, and this repetition itself contains the entire secret of "past and present."

Third Couplet: "水落鱼梁浅,天寒梦泽深。"

Shuǐ luò Yúliáng qiǎn, tiān hán Mèng zé shēn.

Fish Weir looks shallow for water's run low; / The sky is cold, Cloud-Dream Lake's deep in mist, I know.

The poem shifts from reflection to description, drawing the perspective back from the long river of history to the immediate mountains and rivers. Fish Weir Isle is in the Han River near Xiangyang; Cloud-Dream Lake refers to the ancient Yunmeng Marsh, both real geographical features of the Chu region. However, the poet is not merely depicting scenery—the contrast between "shallow" and "deep" is the true poetic core of this couplet. The low water revealing the shallows suggests decline, exposure, something unconcealable; the cold sky over the deep marsh suggests submersion, profundity, immeasurability. This is both the actual weather of the deep autumn Jianghan region and, more importantly, an externalization of the poet's inner landscape: the foundering of his official aspirations is like the shallowness of Fish Weir; the melancholy in his heart is like the depth of Cloud-Dream Lake. Nothing needs explicit statement; the scene itself speaks the emotion. With extremely restrained brushwork, this couplet quietly gathers the grand historical contemplation of the first two couplets back into the poet's own subtle mood, building the fullest emotional momentum for the tears of the final couplet.

Fourth Couplet: "羊公碑字在,读罢泪沾襟。"

Yáng gōng bēi zì zài, dú bà lèi zhān jīn.

The words on Master Yang's stele are still there; / I cannot keep back tears on reading them, I swear.

Here, the floodgates of the poem's emotion burst open. All the preceding reflection, description, and historical remembrance point to this final gaze and these falling tears. The phrase "are still there" seems plain but carries the weight of a thousand jun—the words are there, but Master Yang is long gone; his virtuous governance remains, but the poet achieved nothing; the historic site remains, but human life is fleeting. This "are" is a contrast, an irony, and, most of all, tangible proof of disparate fates. The poet does not describe the stele's content, for what moves him is never the words themselves, but the complete, successful, historically remembered life behind them. Yang Hu achieved everything Meng Haoran failed to achieve: governing for the people, leaving a name for posterity, having people shed tears for him after death. And Meng Haoran's tears are partly for Yang Hu, but even more for himself. Two clear lines of tears—the sorrow of Yang Hu climbing Mount Xian four hundred years ago, and the sorrow of the commoner poet four hundred years later—converge in this moment.

Overall Appreciation

This poem is highly unique within Meng Haoran's oeuvre. It does not excel through the clear sounds of landscape poetry but through historical and philosophical reflection; it does not pursue an ethereal, distant mood but directly confronts the fundamental predicaments and regrets of human life.

The poem's structure can be described as moving from the cosmic to the earthly, from the ancient to the present, from the general to the personal: the first couplet begins with cosmic law, the second returns to the present ascent, the third narrows to the immediate scene, and the fourth condenses into the poet's own tears. Between the four couplets, the scale of time and space constantly shifts, and the emotional intensity continuously builds, until the final line breaks like a dam, irrepressible. This method of layered, step-by-step intensification of emotion appears especially somber and powerful within Meng Haoran's usual "plain words, deep feeling" style.

The poem's most profound tragedy lies not in the surface-level lament of "unrecognized talent," but in the poet's clear awareness of the individual's minuteness and repetitiveness within the long river of history. He knows his sorrow is not unique—Yang Hu grieved, and countless others who vanished into obscurity grieved. He knows that later visitors climbing Mount Xian will also read the stele and shed tears, just as he did. This "conscious repetition" is the true source of despair. Yet he still wrote this poem, still let his tears wet his lapel—this, precisely, is humanity's most stubborn resistance to meaninglessness.

Artistic Features

- Unprecedented, Original Use of Reflective Opening: Among High Tang landscape poets, beginning a poem with such abstract, grand philosophical reflection is a singular case in Meng Haoran's work. Yet the reflection does not fall into didacticism, for it remains closely tied to the act of climbing and the thought of past and present, with a continuous, natural flow of energy.

- Polyphonic Narrative of Spatio-Temporal Structure: The poem moves freely between the three layers of time—"ancient, present, future"—and the three layers of space—"rivers and hills, historic site, stele's words"—forming a polyphonic narrative structure. The era of Yang Hu, the poet's present, and the imagined future ascender resonate simultaneously within the forty words.

- Symbolic Juxtaposition of "Shallow" and "Deep": The third couplet, with its extremely concise language, expresses the deepest feeling. "Shallow" is a metaphor for the foundering of his official path; "deep" is a portrait of the abyssal depth of his state of mind. Not a word of direct reflection is written, yet the sense of his life's journey is fully present.

- Emotional Detonation and Lasting Resonance of the Conclusion: The entire poem builds momentum layer by layer, until the final couplet's "tears on reading them" breaks forth, the emotion reaching its peak. Yet the poet does not write of what comes after the tears fall, or of the descent, but cuts everything off abruptly at this point. The resonance, like a bell, lingers on and on.

Insights

When Yang Hu climbed Mount Xian, he worried about "vanishing into obscurity." When Meng Haoran climbed it, he ached from "failing in his life's ambition." These two sorrows are different: one is the anxiety of a successful man about his posthumous name; the other is the sigh of a disappointed man about his present lot. Yet four hundred years later, Yang Hu's stele remains, and Meng Haoran's poem remains. Both transcended the fate of "obscurity."

This poem teaches us that regret and immortality are never opposing poles. Meng Haoran lacked Yang Hu's achievements, yet with forty characters, he captured the shared sentiments of countless ascenders over millennia, allowing innumerable "obscure" ordinary people in later ages to see themselves reflected in his verse. Is this not another form of "immortality"? In an era rampant with utilitarianism, we habitually judge heroes by success or failure, define value by prominence. Meng Haoran, with his life ending as a commoner and with this tear-soaked poem, offers a gentle yet firm rebuttal: the value of a life lies not only in what it achieves, but also in what it regrets, what it longs for, and in what it sincerely weeps for failing to reach.

Master Yang's stele remains; Meng Haoran's poem remains; a thousand years later, readers still weep upon reading them. These tears are a tribute to the worthy, a pity for the self, and, above all, the full measure of life's own tenacity and refusal to yield.

Poem translator

Kiang Kanghu

About the poet

Meng Haoran (孟浩然), 689 - 740 AD, a native of Xiangyang, Hubei, was a famous poet of the Sheng Tang Dynasty. With the exception of one trip to the north when he was in his forties, when he was seeking fame in Chang'an and Luoyang, he spent most of his life in seclusion in his hometown of Lumenshan or roaming around.