Parting at Xin’an, the Yue guest sighs,

Yearning for Qin’s old land with tearful eyes.

His boat rides the night breeze with ease,

Moonlit tides calm as he flees.

By flowery paths near Xishi’s stone,

Through cloud-peaked walls of Goujian’s throne.

To Mingzhou’s clerks I send this word—

Our mutual grief turns hair to frosty herd.

Original Poem

「送贾恒明府兼寄温张二司户」

綦毋潜

越客新安别,秦人旧国情。

舟乘晚风便,月带上潮平。

花路西施石,云峰句践城。

明州报两掾,相忆二毛生。

Interpretation

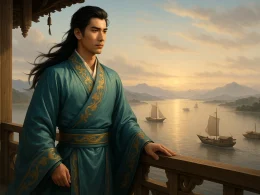

This poem was composed during Qiwu Qian’s exile in Mingzhou, where he served after political setbacks in the capital. Separated from his homeland and fellow exiles—Jia Heng, a local official, and Wen and Zhang, clerks in the administration—Qiwu Qian channels his solitude into this parting verse. Blending farewell sentiments with vivid depictions of Yue’s landscapes, the poem reflects the poet’s longing for companionship amid displacement, weaving personal grief with historical echoes of the region.

First Couplet: "越客新安别,秦人旧国情。"

Yuè kè xīn ān bié, Qín rén jiù guó qíng.

A wanderer in Yue bids farewell at Xin’an—

though we are men of Qin, hearts tethered to our old homeland.

The opening lines juxtapose geography and identity. "Wanderer in Yue" (越客) underscores Qiwu Qian’s estrangement in the southern wilds, while "Xin’an" (新安), a parting point west of Hangzhou Bay, marks the physical and emotional distance from the northern capital. "Men of Qin" (秦人) anchors them to their shared roots in the Guanzhong plains, where the Tang dynasty’s political heart lay. The "old homeland" (旧国情) resonates beyond geography—it is a lost world of courtly camaraderie, now fractured by exile.

Second Couplet: "舟乘晚风便,月带上潮平。"

Zhōu chéng wǎn fēng biàn, yuè dài shàng cháo píng.

Your boat rides the evening’s favoring winds,

as the moon lifts with the calming tide.

Here, nature conspires to ease the journey. The "favoring winds" (晚风便) suggest celestial goodwill, while the moon’s rise with the tide (月带上潮平) paints a harmonious seascape. Yet beneath this serenity lies unspoken melancholy—the poet imagines Jia Heng’s departure as a quiet surrender to nature’s rhythms, a metaphor for their shared resignation to political currents beyond their control.

Third Couplet: "花路西施石,云峰句践城。"

Huā lù Xī Shī shí, yún fēng Gōu Jiàn chéng.

Flower-strewn paths lead past Xishi’s stone,

cloud-peaks crown Goujian’s ancient walls.

The couplet merges natural beauty with historical weight. Xishi (西施), the legendary beauty of Yue, symbolizes the land’s enduring allure, while Goujian (句践), the king who endured humiliation before reclaiming his kingdom, embodies resilience. These references transform the journey into a passage through time—where exile becomes a shared fate with Yue’s storied past. The "cloud-peaks" (云峰) shrouding Goujian’s city hint at obscured glories, mirroring the poet’s own obscured career.

Fourth Couplet: "明州报两掾,相忆二毛生。"

Míng zhōu bào liǎng yuàn, xiāng yì èr máo shēng.

In Mingzhou, greet those two clerks for me—

say the gray-haired one still remembers them.

The closing lines shift from grandeur to intimacy. "Two clerks" (两掾) refer to Wen and Zhang, fellow exiles whose camaraderie once softened the sting of displacement. The self-deprecating "gray-haired one" (二毛生) lays bare Qiwu Qian’s vulnerability—his aging frame a testament to years spent in the wilderness of political disfavor. The request is tender yet haunting: even as Jia Heng moves on, the poet remains suspended in memory, a figure fading like Yue’s ancient ruins.

Holistic Appreciation

This is a farewell poem brimming with human warmth. Across four couplets, the poet paints a complete picture—from personal origins to natural vistas, then to historical echoes and the pull of friendship. From "parting at Xin'an" to "nostalgia for the old country," from "the evening breeze’s ease" to "the moon on calm tides," and onward to "Xishi’s stone" and "Goujian’s city," the emotions deepen layer by layer. The final line, closing with "remembering each other" and "hair turning gray," subtly conveys the poet’s aging solitude and longing for connection.

Written in gentle, classical language with sincere yet understated emotion, this poem stands as one of Qi Wuqian’s late masterpieces, blending landscape meditation with friendship verse.

Artistic Features

- Interweaving of Geography and History

The poet skillfully blends geographical and historical allusions—Xin'an, Qin lands, Mingzhou, the Stone of Xishi, the City of Goujian—into the poem, lending emotional weight to the farewell scene. - Fusion of Scene and Sentiment

Couplets like "The boat rides the evening breeze with ease, / The moon rises with the calming tide" merge natural scenery with human emotion, achieving an elegant subtlety where feeling resides in the landscape, and the landscape breathes with feeling. - Subtle Use of Allusions

Figures like Xishi and Goujian are not explicitly discussed but naturally embedded, enriching the poem’s cultural depth. - Concise and Refined Language

With just twenty-eight characters, the poem is linguistically compact yet rich in imagery, showcasing the restrained and introspective style of Qi Wuqian’s later years.

Insights

More than just a farewell piece, this poem is a genuine emotional record from Qi Wuqian’s period of political disillusionment and southern wandering. Through depictions of scenery, history, and local customs, the poet projects his musings on life, friendship, fleeting time, and belonging. Though "homesickness" is never stated outright, the verses quietly harbor the loneliness of travel and the weight of passing years, reminding us that amid life’s hustle, we must cherish friendship and safeguard the soul’s true home.

About the Poet

Qiwu Qian (綦毋潜 692–c. 755), a native of Ganzhou (modern-day Ganzhou, Jiangxi), was a representative poet of the Landscape and Pastoral School during the High Tang period. He earned the jinshi degree in 726 (the 14th year of the Kaiyuan era) and held official positions such as Right Reminder (You Shiyi) and Editorial Director (Zhuzuo Lang) before retiring to the Jiangnan region. His poetry, renowned for its depictions of reclusive life and natural landscapes, is characterized by a serene and understated style. He exchanged poetic works with Wang Wei, Meng Haoran, and other literary figures. The Complete Tang Poems (Quan Tangshi) preserves 26 of his poems, which stand out distinctly within the High Tang landscape poetry tradition and significantly influenced the development of later Zen-inspired poetry.