The clouds divorced the sky for seven nights,

Spring’s will was burned in their forgetting flight.

A thousand flowers bleed on the fasting road,

While her coach’s perfume strangles a willow’s throat.

My tower weeps windows of liquid glass,

“Swallows, carve her shadow on the grass!”

Spring grief is a lunatic’s cotton maze,

Even nightmares refuse to memorize her face.

Original Poem

「鹊踏枝 · 几日行云何处去」

几日行云何处去?忘却归来,不道春将暮。

百草千花寒食路,香车系在谁家树?泪眼倚楼频独语。双燕来时,陌上相逢否?

冯延巳

撩乱春愁如柳絮,依依梦里无寻处。

Interpretation

This ci poem by Feng Yansi, a master of Southern Tang lyric poetry, exemplifies his signature style of blending delicate feminine sentiment with profound existential melancholy. Through the voice of a lovelorn woman awaiting her wandering lover, Feng crafts a multilayered meditation on time's passage, youth's evanescence, and love's fragility—all framed within the dying days of spring. The work stands as a paradigm of early wanyue (graceful restraint) aesthetics, where every image resonates with unspoken emotional depth.

First Stanza: "几日行云何处去?忘却归来,不道春将暮。"

Jǐ rì xíng yún hé chù qù? Wàng què guī lái, bù dào chūn jiāng mù.

For days, where has that drifting cloud wandered?

You've forgotten to return—

do you not see spring approaches its end?

The opening interrogative—"where has that drifting cloud wandered?"—immediately establishes the central metaphor of the absent lover as rootless vapor. "Drifting cloud" (行云) conveys his capriciousness, while "forgotten to return" (忘却归来) stings with neglected intimacy. The climactic "spring approaches its end" (春将暮) operates on three levels: seasonal decay, the woman's fading youth, and by extension, the Southern Tang dynasty's twilight—Feng's subtle political allegory.

"百草千花寒食路,香车系在谁家树?"

Bǎi cǎo qiān huā hán shí lù, xiāng chē xì zài shuí jiā shù?

Along Cold Feast's paths where a hundred flowers bloom,

to whose gate is your scented carriage tethered now?

The lush "hundred flowers" (百草千花) symbolize both spring's zenith and the temptations distracting the lover. "Cold Feast" (寒食), the Qingming precursor festival, adds cultural poignancy—its grave-sweeping rites contrasting with the lover's revelry. The piercing question—"to whose gate is your scented carriage tethered?" (香车系在谁家树)—masks seething jealousy beneath elegant phrasing, epitomizing wanyue's "more by less" aesthetic.

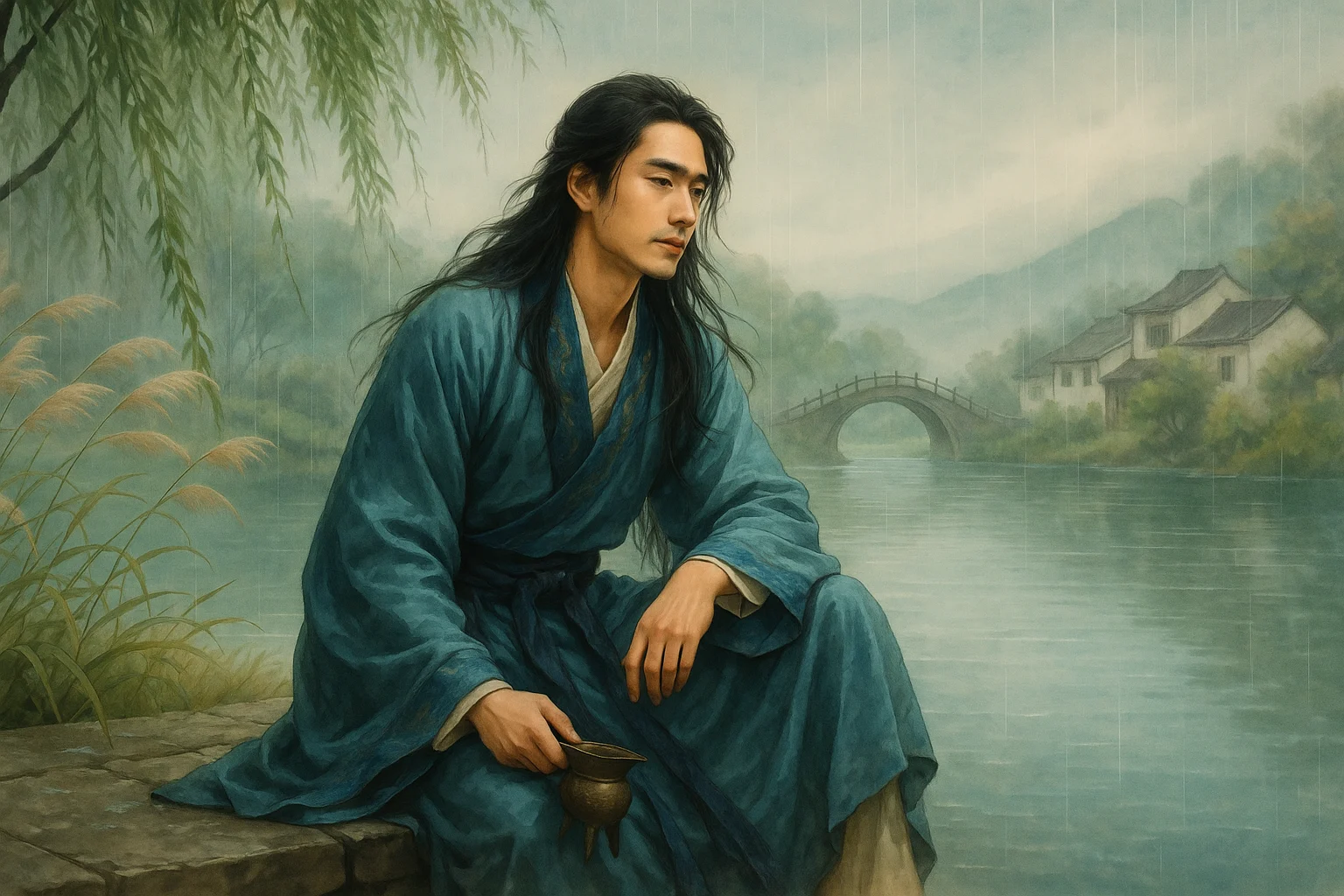

Second Stanza: "泪眼倚楼频独语。双燕来时,陌上相逢否?"

Lèi yǎn yǐ lóu pín dú yǔ. Shuāng yàn lái shí, mò shàng xiāng féng fǒu?

Teary-eyed, I lean on the tower, muttering alone:

"When paired swallows returned,

did you cross paths on the road?"

The woman's physical posture—"teary-eyed, leaning" (泪眼倚楼)—externalizes her emotional collapse. Her soliloquy to swallows (燕), traditional emblems of marital fidelity, underscores her desperate hope against reason. The question—"did you cross paths?"—reveals her delusion that nature might bridge human separation, heightening the pathos.

"撩乱春愁如柳絮,依依梦里无寻处。"

Liáo luàn chūn chóu rú liǔ xù, yī yī mèng lǐ wú xún chù.

My spring sorrows tangle like willow floss,

clinging yet lost even in clinging dreams.

The closing couplet masterfully merges image and emotion. "Willow floss" (柳絮), a classic symbol of life's aimless drift, here embodies her chaotic thoughts. The paradoxical "clinging yet lost" (依依无寻) crystallizes the poem's central tension—between memory's persistence and love's irretrievability. The final "dreams" (梦) suggest her only refuge is illusion, yet even there, her lover remains elusive.

Holistic Appreciation

This ci poem revolves around the theme of "awaiting a lover's return in vain," with emotions unfolding progressively—from anticipation to disillusionment, from fantasy to dream, from resentment to sorrow. Feng Yansi masterfully employs rhetorical questions, metaphorical imagery, and symbolism to craft a tightly structured poem with a gentle yet undulating rhythm. The woman, torn between resentment over her lover’s absence and lingering attachment to their past, immerses herself in a cycle of "sorrow," "gazing," "longing," and "dreaming," all conveyed with poignant sincerity and refined diction.

Three rhetorical questions punctuate the poem, each intensifying the emotional arc:

- "For days, where has the wandering cloud gone?"

- "To whose house is the perfumed carriage tied?"

- "Will we meet again on the road?"

These questions escalate the woman’s emotions from hope to resentment, from resentment to grief, creating a crescendo of feeling—a hallmark of the poem’s artistry.

Artistic Merits

- Tight Structure, Layered Emotional Progression

The three rhetorical questions construct a journey from anticipation to heartbreak, each deepening the emotional weight. - Rich Symbolism, Evocative Imagery

"Wandering cloud," "perfumed carriage," "paired swallows," and "willow catkins" are vivid and laden with meaning, enriching the poem’s allegorical depth. - Lyrical Language, Melancholic Tone

Soft, mellifluous diction and a plaintive cadence evoke the boudoir’s languid sorrow, drawing readers into the woman’s emotional world. - Scene and Sentiment Intertwined, Reality and Illusion Merged

The woman’s solitary murmurs in her chamber mirror her dreamlike searches, blurring the lines between reality and fantasy to amplify artistic resonance.

Insights

This work transcends personal heartache to articulate universal emotional states—"hope," "resentment," "obsession," and "dreaming." It embodies a sorrow that is profound yet restrained, allowing readers to appreciate the aesthetic beauty of lyrical ci while gaining deeper insight into human vulnerability and resilience. This gentle yet profound mode of expression lies at the heart of traditional ci’s enduring emotional power.

About the Poet

Feng Yansi (冯延巳 903 - 960), courtesy name Zhengzhong, was a native of Guangling (modern-day Yangzhou, Jiangsu) and a renowned ci poet of the Southern Tang during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. Rising to the position of Left Vice Director of the Department of State Affairs (Zuo Puye Tongping Zhangshi), he enjoyed the deep trust of Emperor Li Jing. His ci poetry forged a new path beyond the Huajian tradition, directly influencing later masters like Yan Shu and Ouyang Xiu, playing a pivotal role in the transition of ci from "entertainment for musicians" to "literary expression of scholar-officials."