Night chills the flute that sails through moonlit peaks;

Dark paths beguile with a hundred blooms unseen.

The chessmen rest—what world exists beyond this game?

Wine’s gone, the traveler’s heart aches for home.

Original Poem

「梦中作」

欧阳修

夜凉吹笛千山月,路暗迷人百种花。

棋罢不知人换世,酒阑无奈客思家。

Interpretation

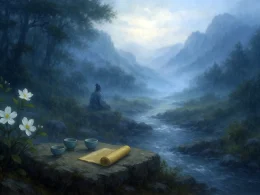

Written around 1049 during Ouyang Xiu's exile to Yingzhou following the failure of the Qingli Reforms, this heptasyllabic quatrain employs dream imagery as a metaphysical lens. Beneath its surreal surface pulses a dual meditation on political disillusionment and existential displacement, where nocturnal visions become allegories for Northern Song intellectuals' fractured realities.

First Couplet: "夜凉吹笛千山月,路暗迷人百种花。"

Yè liáng chuī dí qiān shān yuè, lù àn mí rén bǎi zhǒng huā.

Night-chilled, my flute pierces moonstruck peaks;

Path-dark, a hundred blossoms lure astray.

The couplet constructs a sensory paradox: the auditory clarity of flute notes (吹笛) against visual deception (路暗). The "moonstruck peaks" (千山月) evoke bureaucratic isolation—each mountain a silent witness to exile—while the treacherous blossoms (百种花) symbolize political temptations that obscured reformist paths. The dream's topography mirrors Ouyang's waking dilemma: aesthetic beauty versus ethical navigation.

Second Couplet: "棋罢不知人换世,酒阑无奈客思家。"

Qí bà bù zhī rén huàn shì, jiǔ lán wú nài kè sī jiā.

Chess ends—who noticed the world changed hands?

Wine drained—an exile's helpless homesickness expands.

Here, the Wang Zhi chess典故 transforms into political allegory: the "changed world" (人换世) references Emperor Renzong's purge of reformers, as sudden and imperceptible as a game's conclusion. The visceral shift from communal drinking (酒阑) to solitary yearning (客思家) performs the scholar-official's ultimate solitude—his "home" neither geographical location nor court position, but an irrevocable pre-reform past.

Holistic Appreciation

Comprising four lines that stand independently yet flow seamlessly in meaning, this poem constructs a dreamlike journey rich in poetic symbolism. The poet employs imagery of a cold moon, blooming flowers, a game of chess, and wine-drinking as metaphorical threads, tracing his psychological odyssey through adversity. From solitude to disorientation, transcendence to melancholy, the verses weave an intricate tapestry of illusion and reality, imbued with profound philosophical contemplation. Though born of dreams, it mirrors the wandering spirit and unfulfilled aspirations of waking life, packing remarkable depth and nuance into just four lines.

Artistic Merits

This poem is distinguished by its unconventional conception and distilled language. Though each couplet presents disparate images, they coalesce into a unified narrative of dreams—embedding emotion in scenery and wisdom in reverie. The opening lines depict a silent night and lost path, establishing an aura of mystery and detachment; the subsequent lines invoke classical allusions and mundane reflections to layer expressions of life’s impermanence and nostalgia for home. Masterfully, the poem integrates allusions effortlessly, maintains parallel structure with precision, and balances subtlety with clarity—showcasing Ouyang Xiu’s artistic mastery and his evolution of the Tang-era dream poetry tradition.

Insights

Dreams, though illusory, often carry the weight of our truest emotions. Here, the poet uses dreams as a lens to examine human existence, probing life’s direction amid chaotic, enigmatic visions. For those grappling with hardship, dreams may offer solace for the spirit, yet reality demands steadfast conviction. This poem reminds us: even in the depths of despondency, poetry and thought can kindle light, preserving within life a sanctuary of tenderness and wisdom.

About the Poet

Ouyang Xiu (欧阳修, 1007 - 1072), a native of Yongfeng, Jizhou (present-day Jiangxi Province), emerged as the preeminent literary figure of the Northern Song Dynasty. After attaining the jinshi degree in 1030, he spearheaded a literary reform movement that rejected the ornate Xikun style prevalent at court. As a mentor who nurtured literary giants like Su Shi and Zeng Gong, he laid the foundation for the golden age of Northern Song literature. Recognized as one of the "Eight Great Prose Masters of Tang and Song," Ouyang stands as the pivotal figure in the transformation of Northern Song literary culture.