I met you often when you were visiting princes

And when you were playing in noblemen's halls.

...Spring passes... Far down the river now,

I find you alone under falling petals.

Original Poem

「江南逢李龟年」

杜甫

岐王宅里寻常见,崔九堂前几度闻。

正是江南好风景,落花时节又逢君。

Interpretation

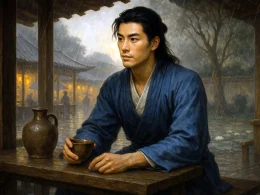

This renowned poem was composed in the spring of 770 CE, the fifth year of the Dali era under Emperor Daizong of Tang—the final year of Du Fu’s life. Drifting to Tanzhou (present-day Changsha, Hunan), the poet unexpectedly encountered the celebrated musician Li Guinian, who was also exiled in the Jiangnan region. Li Guinian had been a court singer during the Kaiyuan and Tianbao eras, renowned among nobles and officials, personally experiencing and symbolizing that golden age of culture and art. This chance reunion of “kindred souls cast adrift” stirred Du Fu’s deepest reflections on the Tang dynasty’s rise and fall, his own life’s vicissitudes, and the fate of art. The resulting poem, with its extremely concise form, carries immense emotional and historical weight, and is hailed as the crowning masterpiece of Du Fu’s seven-character quatrains.

First Couplet: 岐王宅里寻常见,崔九堂前几度闻。

Qí wáng zhái lǐ xún cháng jiàn, Cuī Jiǔ táng qián jǐ dù wén.

In the mansion of Prince Qi I saw you often; / Before the hall of Cui the Ninth, I heard you time and again.

The opening begins with a calm tone, unrolling a long scroll of memory from the High Tang. “The mansion of Prince Qi” and “the hall of Cui the Ninth” were symbolic spaces in the eastern capital Luoyang during the Kaiyuan era, representing flourishing arts and gatherings of cultural elites. “Saw you often” and “heard you time and again” sound casual and effortless, yet precisely convey that in that era of peak prosperity, enjoying the finest art was a normalcy, a daily luxury. The poet, then a young figure who would later become the “Sage of Poetry,” and Li Guinian, a shining star of the artistic world—their “often seeing” and “time and again hearing” are themselves a vivid snapshot of that open, affluent, and culturally rich age. The more ordinary the recollection, the more startling the vast transformation looming behind it.

Second Couplet: 正是江南好风景,落花时节又逢君。

Zhèng shì jiāng nán hǎo fēng jǐng, luò huā shí jié yòu féng jūn.

Now, in the south, the landscape is most lovely; / In the season of falling blossoms, I meet you once more.

Here the brush turns sharply, pulling back from the glorious past to the desolate present. “The landscape is most lovely” is an objective statement, yet also a profound irony. Though the scenery is beautiful, those viewing it are now weathered by upheaval, worn and adrift. The four words “season of falling blossoms” are the soul of the entire poem: they denote both the actual season of the reunion (late spring) and a layered symbol—of the twilight of personal life, the decline of the Tang’s fortune, and the irretrievable fading of all things beautiful. The word “once more” in “meet you once more” seems simple but carries immense weight; it bridges a span of forty years, from the splendor of “the mansion of Prince Qi” to the desolate wandering of “the south… falling blossoms,” encompassing within it the transformation of the nation and the pain of personal fate. The surprise of reunion is wrapped in boundless melancholy and sorrow.

Holistic Appreciation

This seven-character quatrain of only twenty-eight characters is a model of Du Fu’s late artistry—highly condensed in form and intensely concentrated in emotion. The poem employs the technique of “using joyful scenery to convey sorrow, containing thunderous force within plainness.” On the surface, the first two lines are warm reminiscence, the last two a simple account of an unexpected meeting, the tone calm as casual speech. Yet between “saw you often” and “meet you once more” lies the cataclysmic An Lushan Rebellion that utterly altered the fate of the nation and the individual; between “the mansion of Prince Qi” and “the south” is a spatial displacement from the cultural center to the marginalized fringe; between the clear melodies of the golden age “heard… time and again” and the silent drifting of “the season of falling blossoms” is the complete finale of a glorious era.

The poem’s power lies in its vast omissions and endless tension. The poet does not write a single line of direct lament, does not describe how Li Guinian fell into hardship, nor his own distress. Yet all of this is strongly implied through the juxtaposition and contrast of images: “Prince Qi’s mansion” vs. “the south,” “often” vs. “once more,” “lovely landscape” vs. “season of falling blossoms,” allowing readers to fill in the omitted, earth-shattering historical content themselves. This reunion is no longer merely a meeting of two individuals, but an encounter between two “survivors of the High Tang,” a sorrowful echo of a shattered history in a specific time and space.

Artistic Merits

- Juxtaposition of Past and Present, Condensed Time and Space

The poem establishes a clear dichotomy between the “past” (symbolized by Chang’an/Luoyang, the High Tang era, and youth) and the “present” (represented by Jiangnan, a time of decline, and old age). By contrasting specific, illustrious locales (Prince Qi’s mansion, Cui the Ninth’s hall) with an abstract, evocative season (the season of falling blossoms), the poet condenses four decades of monumental upheaval into a brief poetic frame. This compression produces a deeply poignant artistic effect. - Precise Imagery with Profound Symbolic Depth

The phrase “season of falling blossoms” serves as the poem’s core and most potent image. It masterfully merges three layers of meaning: the literal natural scene (late spring with drifting petals), the personal human condition (old age and rootless wandering), and the overarching historical mood (national decline and decay). This imbues the poem with a rich, philosophical resonance that is subtly suggested yet profoundly weighty. - Unadorned Language Veiling Profound Emotion

The verses flow with the natural ease of speech, devoid of rare vocabulary, forced expressions, or explicit lament. Yet beneath this surface of extreme restraint and calm narration surges a profound undercurrent of sorrow—for both personal fate and national destiny. This achieves an artistic pinnacle where immense feeling is conveyed through supreme simplicity, proving that “the plainest form reveals the most vibrant depth.” - Exquisite Structure with Seamless Transitions

The first two lines unfold in a parallel structure, recounting memories of the past. The final two lines pivot sharply to focus on the present encounter. The shift from “hearing” then to “meeting” now, from recollection to immediate reality, feels entirely natural and seamless. The closing line resonates long after the poem ends, akin to the lingering vibrato of a plucked string, leaving the reader with space for endless reflection.

Insights

This work shows us that the greatest poems are sometimes born from the most accidental, ordinary encounters. It reveals a profound historical truth: The upheavals of an era ultimately imprint themselves on the trajectory of every individual’s fate, whether emperor, general, minister, poet, or musician. The figures of Du Fu and Li Guinian together constitute a miniature narrative of a civilization’s transition from prosperity to decline.

The enlightenment this poem offers extends beyond literature: it concerns memory, time, and the transmission and rupture of civilization within individual lives. It reminds us to cherish those “encounters” that carry shared culture and memory, for within the flow of time, they are precious coordinates confirming who we are and where we came from. Meanwhile, the imagery of “the season of falling blossoms” also warns us that for individuals, society, and even civilization, “lovely landscape” does not necessarily mean a truly “good season.” At historical turning points, there must be a clarity and compassion that penetrates appearances to perceive the essence. This is precisely the most solemn and wisest sigh Du Fu left for posterity at the end of his life.

Poem translator

Kiang Kanghu

About the poet

Du Fu (杜甫), 712 - 770 AD, was a great poet of the Tang Dynasty, known as the "Sage of Poetry". Born into a declining bureaucratic family, Du Fu had a rough life, and his turbulent and dislocated life made him keenly aware of the plight of the masses. Therefore, his poems were always closely related to the current affairs, reflecting the social life of that era in a more comprehensive way, with profound thoughts and a broad realm. In his poetic art, he was able to combine many styles, forming a unique style of "profound and thick", and becoming a great realist poet in the history of China.