We part at the Pavilion Old;

The river flows its water cold.

Above we see trees not in bloom.

Below the vernal grass in gloom.

I ask a wanderer if we go astray;

He says an ancient poet took this way.

The way extends to the west capital,

Where floating clouds at sunset veil the palace hall.

Heart-broken here and now I part with you.

How can we bear to hear songs of adieu?

Original Poem:

「灞陵行送别」

李白

送君灞陵亭,灞水流浩浩。

上有无花之古树,下有伤心之春草。

我向秦人问路歧,云是王粲南登之古道。

古道连绵走西京,紫阙落日浮云生。

正当今夕断肠处,骊歌愁绝不忍听。

Interpretation

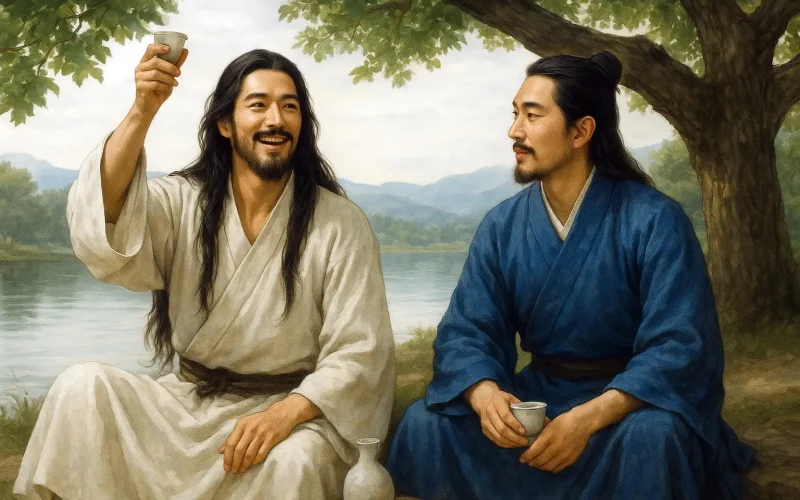

This poem by Li Bai takes the famous Tang Dynasty farewell site "Ba Ling" as its subject. Located southeast of Chang'an, Ba Ling was where friends traditionally parted before long journeys. With elegant language and profound emotion, the poem depicts a farewell scene through the interweaving of natural imagery and historical allusions, revealing the poet's historical consciousness and humanistic spirit that transcend personal feelings. While superficially about "seeing someone off," the work ultimately uses "life's separations" as its philosophical theme, expressing both personal sorrow and concerns for the nation with profound depth.

First Couplet: "送君灞陵亭,灞水流浩浩。"

Sòng jūn Bàlíng tíng, bà shuǐ liú hàohào.

I bid you farewell at Ba Ling Pavilion, Where the Ba River flows vast and endless.

The opening lines specify the farewell location and scene with concise yet meaningful language. The "vastness" of the Ba River describes both the actual scene and implies boundless sorrow of parting. Li Bai often uses nature as a mirror for emotions; here the water symbolizes continuous, unending feeling. Ba Ling Pavilion is not just a geographical landmark but also a symbolic site of farewell in the hearts of ancient literati. The poet stands by the pavilion, watching his friend depart, his emotions as relentless as the river's flow—mingling reluctant farewell with silent wishes for the future. This establishes the poem's artistic foundation of "emotion arising from scene, scene embodying emotion."

Second Couplet: "上有无花之古树,下有伤心之春草。"

Shàng yǒu wú huā zhī gǔ shù, xià yǒu shāngxīn zhī chūn cǎo.

Above, ancient trees bare of blossoms; Below, heartbroken spring grass.

These lines intensify the parting atmosphere through strong contrast. "Blossomless ancient trees" symbolize the passage of time and the changes of the world; "heartbroken spring grass," though verdant and growing, is imbued with melancholy, creating a counterpoint beauty of "writing death through life, expressing sorrow through spring." This couplet describes both scene and heart—in the poet's eyes, even grass understands parting grief, and ancient trees share the sorrow. Li Bai excels at projecting emotion onto objects, here turning natural scenes into extensions of the soul, allowing poignant emotion to flow naturally from within.

Third Couplet: "我向秦人问路歧,云是王粲南登之古道。"

Wǒ xiàng Qín rén wèn lù qí, yún shì Wáng Càn nán dēng zhī gǔ dào.

I ask a native of Qin about the fork in the road, Who says it's the ancient path Wang Can took southward.

This couplet shifts to a historical dimension. Through the allusion to "Wang Can's southward journey," the poem mirrors the current farewell with historical exile. Wang Can, full of sorrow during his southward flight from turmoil, reflects Li Bai's concerns for his friend's future and his sighs over an unstable world. "Asking a native of Qin about the road" is both literal and symbolic of life's confusion and choices. This integration of personal emotion into historical narrative broadens the poetic realm and deepens the emotional resonance.

Fourth Couplet: "古道连绵走西京,紫阙落日浮云生。"

Gǔdào liánmián zǒu xījīng, zǐ què luòrì fúyún shēng.

The ancient path winds continuously toward the Western Capital; Purple palaces see the sunset, floating clouds arise.

Here the "ancient path" and "purple palaces" reflect each other, forming a vast, majestic picture. "Sunset" and "floating clouds" are richly symbolic—the sunset represents the passage of time and life's decline, while clouds suggest political instability and human unpredictability. Li Bai often uses grand scenes to convey deep thought; here, through spatial expansion and temporal passage, the poem elevates personal sorrow to lament over the rise and fall of nations. This couplet moves from scene to philosophy, possessing strong historical consciousness and romantic pathos.

Final Couplet: "正当今夕断肠处,骊歌愁绝不忍听。"

Zhèngdāng jīnxī duàncháng chù, lí gē chóu jué bù rěn tīng.

Tonight, here at this heartbreaking place, The farewell song's sorrow is too much to bear.

The concluding couplet brings the parting emotion to its peak. "Heartbreaking," "sorrowful beyond bearing," and "unable to listen" are extreme expressions of emotion, creating resonance between rhythm and feeling. "Farewell song" (Li Ge), traditionally sung at partings, deepens the grief. Using this imagery of ancient ritual, Li Bai intertwines personal tenderness with cultural melancholy, making the farewell not just an individual event but an eternal theme of life. Though sorrowful, the poet dissolves life's impermanence through poetry, displaying the unique charm of Li Bai's work where transcendence and sentiment coexist.

Holistic Appreciation

Through Li Bai's use of historical allusions like Ba Ling, the ancient path, and Wang Can, this work expresses the complex emotions of parting, blending historical weight with personal feeling. The poem's scenic descriptions are closely linked to emotion; elements like ancient trees, spring grass, sunset, and floating clouds not only enhance the poetic atmosphere but also profoundly express the poet's reluctance to part and his anxiety over current events. Through this poem, Li Bai reveals a complex inner world—not only bidding farewell to a friend but also deeply contemplating the nation's fate and sighing over epochal changes.

Artistic Merits

- Fusion of Scene and Emotion, Profound Conception: Li Bai skillfully blends natural scenery, historical allusions, and personal emotion, creating a layered emotional space within the poem. The Ba River, ancient trees, spring grass, and sunset all serve as vessels of emotion, making the poetic imagery complete and moving.

- Interweaving of History and Reality: "Wang Can's southward journey" not only laments ancient misfortunes but also metaphorically expresses the poet's unease and concern about real society. This historical consciousness elevates the poem beyond personal sorrow to include cultural and political reflection.

- Concise Language, Lingering Rhythm: The lines are short yet rich in meaning, with five and seven characters alternating, the syllables flowing like waves of the Ba River, possessing both lyrical softness and majestic momentum.

- Skillful Use of Symbolism: Li Bai excels at using concrete images to convey abstract emotions; "blossoms," "grass," "clouds," and "water" all carry symbolic meaning. Through repeated symbolic transformation, the poetic meaning progresses in layers, deepening the emotion.

Insights

This is not merely a poem of farewell but a lyrical expression about life, friendship, and time. Through "the Ba River flows vast and endless," Li Bai writes the inevitability of life's long journey and parting, helping us understand that worldly affairs are like water—meetings and separations are unpredictable, and only by facing farewell with a calm heart can we move forward. The deep friendship contained in the poem also reminds us to cherish the people and emotions of the present. Though parting is painful, its brevity makes friendship all the more precious; "the farewell song's sorrow" teaches us that true feeling need not last forever, only sincerity endures. Simultaneously, Li Bai uses the allusion of "Wang Can's southward journey" to express concern, elevating personal sorrow into cultural memory and historical reflection. With a mind that transcends personal joy and sorrow, the poet inspires people to protect affection and faith amid change.

This poem tells us: parting is not the end but part of life. Understanding farewell, cherishing encounters, and moving forward bravely are the profound meanings Li Bai conveys in this poem.

Poem translator

Xu Yuanchong(许渊冲)

About the poet

Li Bai (李白), 701 - 762 A.D., whose ancestral home was in Gansu, was preceded by Li Guang, a general of the Han Dynasty. Tang poetry is one of the brightest constellations in the history of Chinese literature, and one of the brightest stars is Li Bai.