At dusk in the palace, from the emperor parted,

Deep chambers, moon like frost, chill-hearted.

Sorrow fills the Long Faith Palace's space,

While fireflies toward the Sunlit Palace race.

Dew-drenched red orchids wither and die,

Autumn withers jade trees with a sigh.

Only the joy-union fan remains,

Hidden in its case from now on, in chains.

Original Poem

「相和歌辞 · 婕妤怨」

刘方平

夕殿别君王,宫深月似霜。

人愁在长信,萤出向昭阳。

露裛红兰死,秋凋碧树伤。

惟当合欢扇,从此箧中藏。

Interpretation

"Song of Harmony" is an ancient Yuefu title dating back to the Han, Wei, and Six Dynasties periods, often used to express the sorrows of palace life. Liu Fangping lived during the Dali and Guangde eras of Emperor Daizong of Tang—a time of eunuch dominance, regional warlordism, and widespread frustration among court officials and scholars. This poem continues the tradition of "palace grievance poetry," adopting a persona to voice the loneliness and despair of a neglected palace lady. "Jieyu" (婕妤) was originally a rank for imperial consorts during the Han Dynasty; Tang poets often used it to represent secluded and discontented palace women. Through the voice of a Jieyu, the poet depicts not only the desolate isolation within the cold palace but also reflects the Tang scholars’ own experience of unrecognized talent and suppressed anguish.

First Couplet: "夕殿别君王,宫深月似霜。"

Xī diàn bié jūnwáng, gōng shēn yuè sì shuāng.

At dusk in the hall, she bids the monarch farewell;

The palace is deep, the moon like frost.

These opening lines identify the source of grievance: loss of favor and separation. "Dusk" (夕 xī) implies fading light, symbolizing the end of imperial favor; "deep palace" (宫深 gōng shēn) conveys isolation and oppression; "moon like frost" (月似霜 yuè sì shuāng) intensifies the cold atmosphere. The moon, naturally pure and beautiful, becomes a symbol of neglect and solitude when contrasted with the lonely lady. Emotion is embedded within the scenery, skillfully projecting inner desolation onto the moonlight.

Second Couplet: "人愁在长信,萤出向昭阳。"

Rén chóu zài Chángxìn, yíng chū xiàng Zhāoyáng.

Grief-stricken, she dwells in Changxin Palace,

While fireflies drift toward Zhaoyang Hall.

This couplet employs historical allusion. Changxin Palace was where Empress Xu, neglected by Emperor Cheng of Han, lived in seclusion—a symbol of lost favor; Zhaoyang Hall was where the favored Consort Zhao resided. The contrast between "Changxin" and "Zhaoyang" highlights the lady’s isolation after falling out of favor. "Fireflies drifting toward Zhaoyang" is richly symbolic: these tiny, light-bearing insects, seemingly overreaching, represent her silent longing—fruitlessly chasing the emperor’s favor, destined to remain unheard. Through subtle imagery, the poet profoundly expresses the loneliness and sorrow of the neglected.

Third Couplet: "露裛红兰死,秋凋碧树伤。"

Lù yì hóng lán sǐ, qiū diāo bì shù shāng.

Dew saturates the red orchid, till it dies;

Autumn withers the green trees, wounding the heart.

This couplet uses natural imagery to mirror the lady’s state. "Red orchid" (红兰 hóng lán) represents beauty and vibrancy, but drenched by dew, it withers—a metaphor for the consort’s faded youth; "green trees" (碧树 bì shù), evergreen yet decaying in autumn, symbolize transient beauty and prosperity. The verbs "saturates" (裛 yì) and "withers" (凋 diāo) are vivid, depicting nature’s decline while hinting at human unpredictability and emotional shifts. Through the decay of flowers and trees, the poem reflects the lady’s lost youth and melancholy.

Fourth Couplet: "惟当合欢扇,从此箧中藏。"

Wéi dāng héhuān shàn, cóngcǐ qiè zhōng cáng.

All that remains is the love-union fan,

From now on hidden away in its case.

The poem concludes with the "love-union fan" (合欢扇 héhuān shàn). The union pattern symbolizes marital love and lasting affection, but now it is stored away, representing bygone favor and love. The word "hidden" (藏 cáng) carries deep meaning: emotional traces are forcibly concealed, and past happiness exists only in memory. The ending is subtle yet intensifies the poem’s anguish.

Holistic Appreciation

The poem progresses layer by layer: beginning with the direct scene of "bidding the monarch farewell," moving to the contrast between Changxin and Zhaoyang through allusion, then expressing emotion through autumn imagery of decay, and finally concluding with the symbolic "love-union fan." The poet captures the secluded consort’s loneliness with delicate and heartfelt depth.

The value of the poem lies not only in its depiction of palace grievance but also in its profound寓意 (yùyì, implied meaning): the sorrow of the Jieyu embodies the poet’s lament on life’s unpredictability and personal disappointment. The desolation deep within the palace resonates with the despair of scholars’ thwarted careers. Liu Fangping excels at revealing greatness in smallness—using a female persona to express hidden sorrow, he implies his own inner world.

Artistic Merits

- Persona narrative, emotion within scenery: The poet speaks through the Jieyu’s voice; fiction contains genuine feeling, allowing readers to deeply grasp the loneliness and helplessness.

- Allusions enhancing depth: Changxin and Zhaoyang are not just palace names but carry historical and cultural weight, enriching the poem’s significance.

- Scene and emotion fused, symbolism abundant: The moon like frost, dying orchid, and withering trees—each image blends scene and mood, making nature a reflection of the heart.

- Subtle ending, far-reaching symbolism: The "love-union fan" transforms from a symbol of love to one of grievance, conveying deep meaning and concluding with lasting resonance.

Insights

This is not merely a palace grievance poem but a fable on life’s impermanence and emotional disillusionment. It reminds us: favor, like moonlight, is cold and fleeting; love, like an orchid, blooms then fades. Facing life’s changes, the only endurance lies in inner steadfastness and self-possession. For modern readers, this poem teaches that even in isolation and neglect, one must learn self-comfort and self-fulfillment, without placing all hope on external things or others.

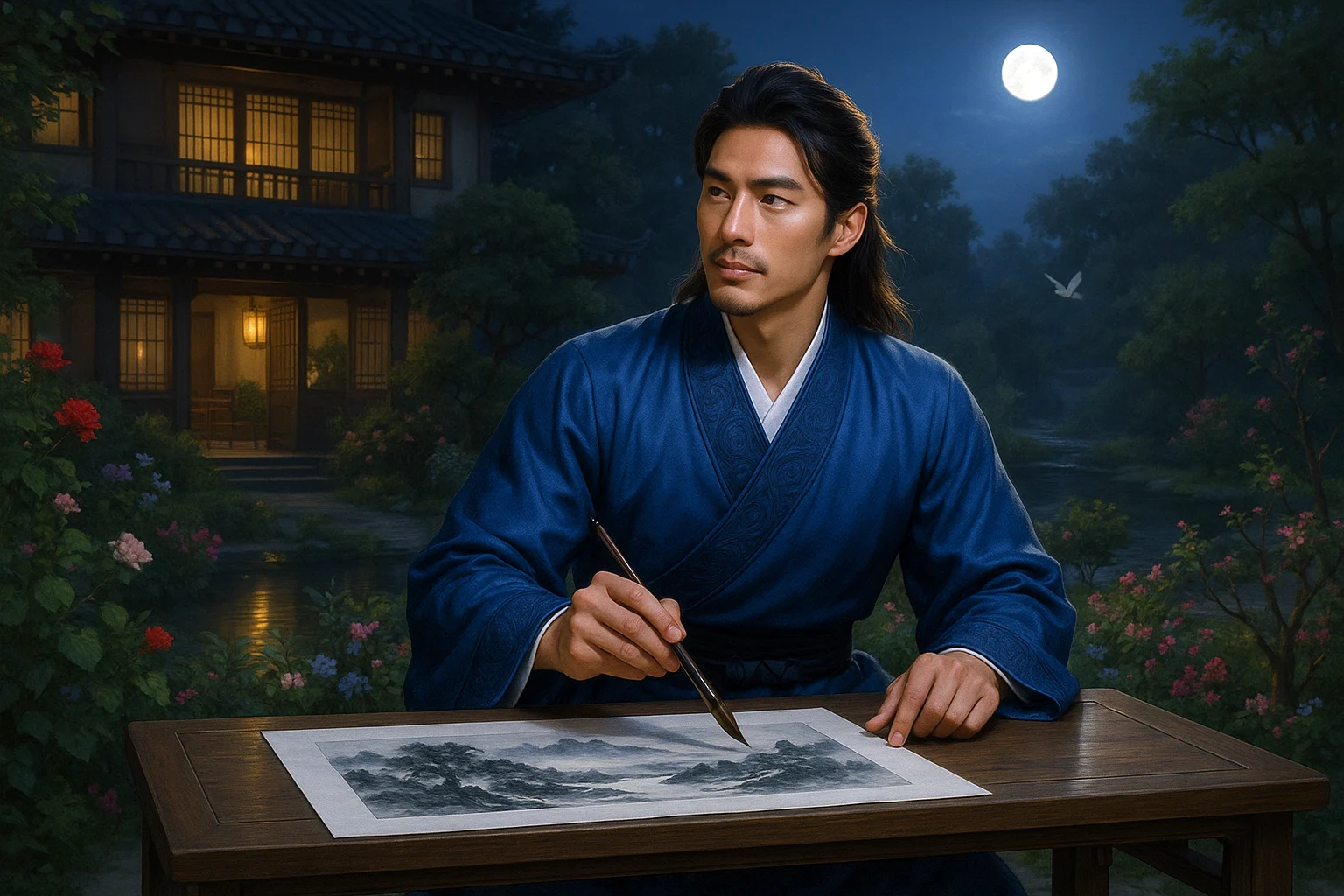

About the Poet

Liu Fangping (刘方平 c. 742 – c. 785), a native of Luoyang in Henan. A recluse-poet and painter spanning the High to Mid-Tang period, he distinguished himself with a delicate and subtle poetic style skilled in depicting boudoir lament and moonlit nights. Though only 26 of his poems survive in the Complete Tang Poems, works like Moonlit Night and Spring Lament secured his place in the canonical hall of Tang poetry. Hailed as "the pure voice of the High Tang and the herald of the Mid-Tang," his poetry fused the lucidity of the Qi-Liang style with Zen serenity, profoundly influencing the later ci lyric tradition and Heian-era Japanese women's literature.