"Leisure" they say—yet leisure never stays,

Secret cares haunt my mind in countless ways.

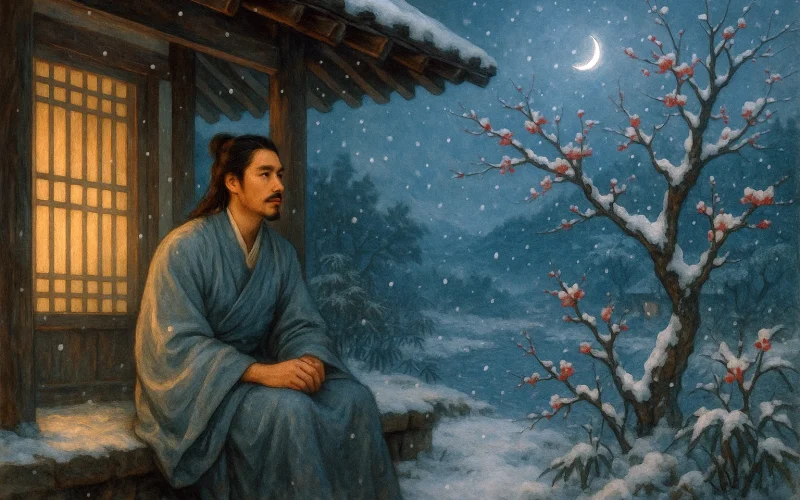

I rise, cloak-draped, hearing snow's nightly song,

Watch moonlit flakes before the dawn's new throng.

Plum boughs seem lonelier in this frozen air,

My hair—like reed-thatch—bares solitude's despair.

Snowflakes know not the sorrows humans keep,

In wind they frolic, swirling in playful heap.

Original Poem

「和汤叔度雪」

杨万里

道得闲来尽未闲,颇缘幽事搅心间。

卧听雪作披衣起,不待天明带月看。

更觉梅枝殊摘索,只惊蓬鬓却羁单。

飞花岂解知人意,风里时时戏作团。

Interpretation

Composed during Yang Wanli's late years, this lyric exemplifies Southern Song literati's snow-viewing tradition—where nature observation becomes existential meditation. Written in response to a friend's poem, it transcends mere description to reveal the paradox of "leisure without repose," blending crystalline imagery with mortal fragility in signature Chengzhai Style.

First Couplet: "道得闲来尽未闲,颇缘幽事搅心间。"

Dào dé xián lái jìn wèi xián, pō yuán yōu shì jiǎo xīn jiān.

"Now at leisure"—

yet never truly still—

subtle disquiets

churn beneath calm.

The opening dismantles the Confucian ideal of serene retirement. Yang's paradox ("leisure without repose") exposes the Song intellectual's perpetual unrest—where political exile and aging amplify nature's beauty with human transience.

Second Couplet: "卧听雪作披衣起,不待天明带月看。"

Wò tīng xuě zuò pī yī qǐ, bù dài tiān míng dài yuè kàn.

Abed, I hear snow's birth—

throw on robes, rise—

not waiting for dawn

but moonlight's silver gaze.

Sensory immediacy propels action: the poet's trajectory from horizontal ("abed") to vertical ("rise") mirrors snow's descent. "Moonlight's silver gaze" (带月看) transforms celestial light into active observer, reversing traditional subject-object dynamics between man and nature.

Third Couplet: "更觉梅枝殊摘索,只惊蓬鬓却羁单。"

Gèng jué méi zhī shū zhāi suǒ, zhǐ jīng péng bìn què jī dān.

Plum boughs glisten

with exceptional grace—

startling my mirror:

disheveled hair, exile's white.

The plum-snow contrast (floral endurance vs. ephemeral crystals) collapses when confronted with the poet's aging reflection. "Exile's white" (羁单) carries dual weight—political displacement and mortality's advance—both intensified by nature's timeless beauty.

Fourth Couplet: "飞花岂解知人意,风里时时戏作团。"

Fēi huā qǐ jiě zhī rén yì, fēng lǐ shí shí xì zuò tuán.

Flying blossoms—

do they fathom human sorrow?

In wind, they frolic,

spinning like children.

The finale's rhetorical question underscores nature's sublime indifference. Personified snowflakes ("flying blossoms") dance obliviously, their playful spirals mocking human gravity. This ecological irony—nature's joy accentuating man's isolation—prefigures modern environmental melancholia.

Holistic Appreciation

Yang constructs a quadruple exposure: auditory snow ("hear its birth"), lunar-lit observation, botanical-mineral hybridity (snow-plum), and finally kinetic flurries. Through this sensory cascade, he maps the scholar's dilemma—how to reconcile nature's cyclical splendor with linear human decay.

The poem's tension lies in its dual movement: outward toward snow's beauty ("moonlight's gaze"), inward toward mortal awareness ("exile's white"). This push-pull dynamic mirrors Confucian-Daoist negotiations—engagement with nature's spectacle versus acceptance of its indifference.

Artistic Merits

- Paradox as Structure

The opening "leisure without repose" (闲未闲) establishes a conceptual framework that permeates every image. - Chronometric Play

"Not waiting for dawn" rejects solar time for lunar time, privileging poetic urgency over diurnal rhythm. - Botanical Mirroring

The plum-snow juxtaposition reflects the poet's own duality—enduring spirit (plum) versus ephemeral form (snow/hair). - Kinetic Irony

Snowflakes' carefree "spinning" (戏作团) highlights human gravity through contrast, a masterstroke of negative space.

Insights

Yang Wanli's snowscape reveals nature as both solace and rebuke. Its beauty offers temporary transcendence ("moonlight's gaze"), yet its indifference ("do they fathom sorrow?") underscores existential solitude. For contemporary readers, this duality resonates deeply in our age of ecological crisis—where nature's splendor persists despite human suffering.

The poem ultimately suggests that true "leisure" requires embracing this paradox: to marvel at snow's dance while acknowledging its disregard for our mortality. In Yang's vision, artistic creation bridges this divide—his poem becomes the mirror where snow and soul briefly align.

About the Poet

Yang Wanli (杨万里 1127 - 1206), a native of Jishui in Jiangxi, was a renowned poet of the Southern Song Dynasty, celebrated as one of the "Four Great Masters of the Restoration" alongside Lu You, Fan Chengda, and You Mao. He attained the jinshi degree in 1154 and rose to the position of Academician of the Baomo Pavilion. Breaking free from the constraints of the Jiangxi School of Poetry, he pioneered the lively and natural "Chengzhai Style," advocating for learning from nature and employing plain yet profound language. His poetry, often drawing inspiration from everyday life, profoundly influenced later schools of lyrical expression, particularly the Xingling (Spirit and Sensibility) School.