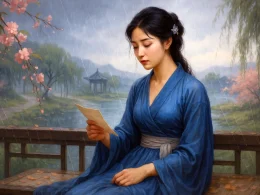

Wind and rain mournful as late autumn’s gloom,

Crows return, doors shut—monks chant in quiet room.

Thick clouds veil thousand peaks’ majestic grace,

Torrents roar through valleys, flooding space.

Temple bells wake dreams—vain gazes linger,

News from afar—letters drowned in river’s finger.

My square-face fate* bars lordly state,

Envying Ban Chao’s fame? Too late.

Original Poem

「柳州开元寺夏雨」

吕本中

风雨潇潇似晚秋,鸦归门掩伴僧幽。

云深不见千岩秀,水涨初闻万壑流。

钟唤梦回空怅望,人传书至竟沈浮。

面如田字非吾相,莫羡班超封列侯。

Interpretation

Composed during Lü Benzhong's exile in Liuzhou amid the Jin invasion's aftermath, this poem encapsulates the Southern Song's fractured spirit. Written at Kaiyuan Temple, its summer storm imagery becomes a vessel for national grief and thwarted ambition—where nature's tumult mirrors dynastic collapse.

First Couplet: "风雨潇潇似晚秋,鸦归门掩伴僧幽。"

Fēngyǔ xiāoxiāo sì wǎnqiū, yā guī mén yǎn bàn sēng yōu.

The rain whispers autumn in midsummer,

crows nest, gates shut—monks guard the quiet.

The dissonant "summer-as-autumn" (似晚秋) immediately frames dislocation. Shuttered gates and returning crows construct a tableau of retreat—both physical (monastery) and psychological (resignation).

Second Couplet: "云深不见千岩秀,水涨初闻万壑流。"

Yún shēn bújiàn qiān yán xiù, shuǐ zhǎng chū wén wàn hè liú.

Clouds bury the peaks' grace;

swollen rivers roar through unseen valleys.

Here, obscured vistas (云深不见) symbolize obscured ambitions; the audible-but-invisible torrents (万壑流) evoke the Jin invasion's distant yet overwhelming threat. Sensory deprivation (sight blocked, sound amplified) mirrors political helplessness.

Third Couplet: "钟唤梦回空怅望,人传书至竟沈浮。"

Zhōng huàn mèng huí kōng chàngwàng, rén chuán shū zhì jìng chénfú.

Temple bells shatter dreams—

only vacant gazing remains.

A letter arrives at last,

to tell me I'm still adrift.

The bell's Buddhist transcendence (钟唤梦回) ironically underscores earthly attachments. The long-awaited letter (书至), rather than anchoring, confirms rootlessness (沈浮)—a masterstroke of thwarted expectation.

Fourth Couplet: "面如田字非吾相,莫羡班超封列侯。"

Miàn rú tián zì fēi wú xiàng, mò xiàn Bān Chāo fēng lièhóu.

My face—square as a field character—

bodes no noble fate.

Spare me envy of Ban Chao's

frontier marquisate.

The "field-character face" (田字相), referencing physiognomic traditions, becomes self-mockery: integrity without opportunity. Ban Chao's military glory (班超封侯) highlights Lü's civilian impotence in wartime—a rejection of ambition that rings with quiet fury.

Holistic Appreciation

Moving from cloistered stillness to torrential unseen forces, the poem mirrors the scholar's journey from retreat to reckoning. The summer storm's false autumn (似晚秋) initiates a sensory unmaking: vision fails ("clouds bury peaks"), hearing intensifies ("rivers roar"), and even touch dissipates ("letter…adrift"). The climax—rejecting Ban Chao's heroics—transforms resignation into moral stance: in fractured times, the square-faced man's duty is witness, not conquest.

Artistic Merits

- Dissonant Temporality

"Summer-as-autumn" (似晚秋) destabilizes seasonal norms, paralleling the dynasty's unnatural rupture. - Sensory Subversion

Blocked sightlines (云深不见) versus amplified sound (万壑流) enact disorientation—a metaphor for political opacity. - Epistolary Irony

The awaited letter's futility (竟沈浮) subverts conventional solace, deepening exile's ache. - Physiognomic Paradox

The "field-character face" (田字相)—emblematically upright yet prognostically plain—encapsulates the upright scholar's wartime irrelevance.

Insights

Lü's poem articulates a Southern Song dilemma: how to reconcile Confucian service with Daoist withdrawal when the state itself is fragmenting. His monastic summer becomes a crucible for this tension—the bells' Zen clarity versus the rivers' chaotic roar. The rejection of Ban Chao's model suggests a new ethic: in eras where heroism is impossible, integrity lies in steadfast witness, "square-faced" and unyielding. For modern readers, it poses a timeless question: how to maintain moral shape when the world dissolves into flood.

About the Poet

Lü Benzhong (吕本中 1084 - 1145), a native of Shouxian in Anhui, was a renowned poet and Neo-Confucian scholar of the Southern Song Dynasty. As a key theorist of the Jiangxi Poetry School, he proposed the concept of "living method" (huofa), advocating for natural variation within established poetic rules. With over 1,270 surviving poems, his Genealogy of the Jiangxi Poetry School (Jiangxi Shishe Zongpai Tu) established Huang Tingjian as the school's patriarch, profoundly influencing Song poetic theory and serving as a bridge between the Jiangxi School and the Four Masters of the Mid-Song Revival.