Ten thousand plum scars bleed from tortured limbs,

Still lusting, they feign snow’s necrotic dance.

Last revels dissolved like pus from wounds,

Sobriety’s gangrene spreads by chance.

Tower—a cold meat locker stacked with hills,

Geese—telegrams from rotted loves long dead.

I fossilize at this railing—nothing comes—

Mermaid silk bandages soak where tears embed.

Original Poem

「鹊踏枝 · 梅落繁枝千万片」

梅落繁枝千万片,犹自多情,学雪随风转。

昨夜笙歌容易散,酒醒添得愁无限。楼上春山寒四面,过尽征鸿,暮景烟深浅。

冯延巳

一晌凭栏人不见,鲛绡掩泪思量遍。

Interpretation

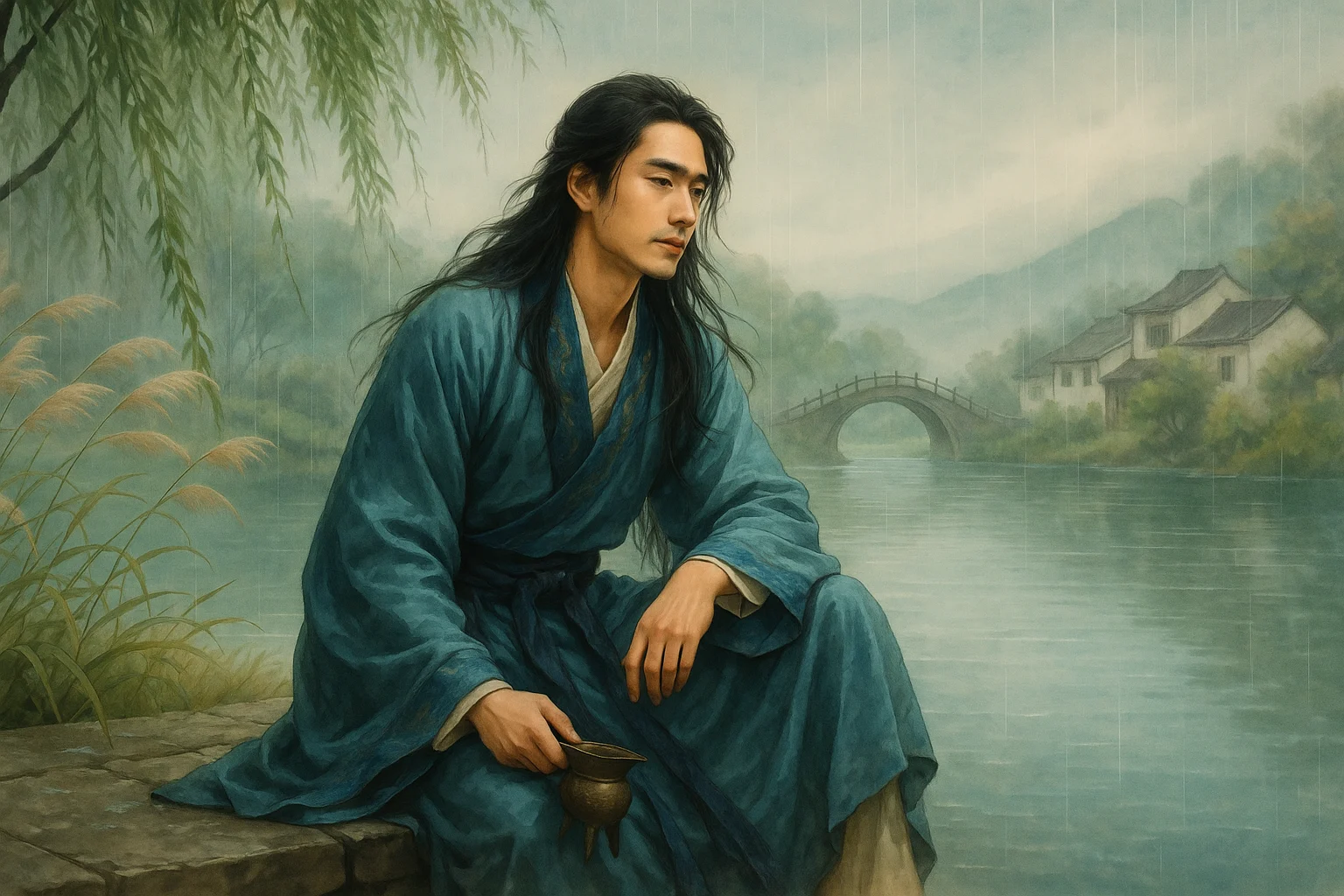

This ci, likely composed during Feng Yansi's service under Emperor Li Jing of the Southern Tang, reflects the poet's nuanced understanding of impermanence—both in love and political life. Through the voice of a lovelorn woman, Feng crafts a poignant meditation on fleeting joy and enduring sorrow, using falling plum blossoms, fading banquets, and distant wild geese as layered metaphors for life's ephemeral nature. The poem's delicate imagery and emotional depth exemplify Feng's mastery of the wanyue (graceful restraint) tradition, where personal longing subtly mirrors broader existential contemplation.

First Stanza: "梅落繁枝千万片,犹自多情,学雪随风转。"

Méi luò fán zhī qiān wàn piàn, yóu zì duō qíng, xué xuě suí fēng zhuǎn.

Plum blossoms cascade from laden branches—

thousands upon thousands of petals,

still tenderhearted, mimicking snow as they twirl in the wind.

The opening lines immerse the reader in a spectacle of falling plum blossoms, their sheer number ("thousands upon thousands") evoking both beauty and transience. By anthropomorphizing the petals as "tenderhearted" (多情), Feng infuses them with emotional weight—their dance is not just a natural phenomenon but a conscious, almost wistful performance. The comparison to snow ("mimicking snow") deepens the sense of fragility, suggesting that love, like blossoms or snowflakes, is destined to dissolve.

"昨夜笙歌容易散,酒醒添得愁无限。"

Zuó yè shēng gē róng yì sàn, jiǔ xǐng tiān dé chóu wú xiàn.

Last night’s flute-song banquet scattered too soon—

sober now, I’m left with boundless sorrow.

Here, Feng contrasts the evanescence of revelry ("scattered too soon") with the lingering ache of solitude. The word "easily" (容易) underscores how quickly joy slips away, while "boundless sorrow" (愁无限) amplifies the void left behind. The shift from communal celebration to private melancholy mirrors the poet’s own life—caught between courtly splendor and the inevitability of loss.

Second Stanza: "楼上春山寒四面,过尽征鸿,暮景烟深浅。"

Lóu shàng chūn shān hán sì miàn, guò jìn zhēng hóng, mù jǐng yān shēn qiǎn.

From the tower, spring mountains exhale chill on all sides—

the last migrating geese vanish,

while dusk’s haze thickens and thins.

The stanza expands the perspective outward, from the intimate space of the tower to the vast, indifferent landscape. The "spring mountains" (春山), typically a symbol of renewal, here emit an unseasonable chill, reflecting the speaker’s inner desolation. The departing geese (征鸿), a classical motif for separation, emphasize the finality of absence, while the shifting dusk haze (暮景烟) mirrors the uncertainty of memory—what was once clear now blurs.

"一晌凭栏人不见,鲛绡掩泪思量遍。"

Yī shǎng píng lán rén bú jiàn, jiāo xiāo yǎn lèi sī liang biàn.

Leaning on the railing, still you don’t appear—

I dab my tears with silken gauze,

retracing every memory, again and again.

The poem closes with a quiet yet devastating gesture. The speaker’s prolonged vigil ("leaning on the railing") yields nothing, and the act of wiping tears with "silken gauze" (鲛绡)—a luxurious fabric associated with mermaid’s silk in Chinese lore—hints at both refinement and unspoken grief. The final line, "retracing every memory" (思量遍), captures the cyclical nature of longing, where the mind replays moments that can never return.

Holistic Appreciation

The poem begins with falling plum blossoms, embedding emotion within the scenery, then transitions from the immediate scene to reality, before returning from a distant gaze to an inner monologue—forming a structure that expands outward before drawing inward. The imagery—plum blossoms, celebratory music, cold mountains, migrating geese, evening mist, and mermaid silk—interweaves to trace an emotional arc: fleeting reunion, inevitable parting, and endless longing.

Feng Yansi’s brilliance lies in never stating sorrow directly, but instead letting objects and atmosphere permeate emotion, allowing readers to intuit the poet’s shifting mood through the landscape’s flow. Unlike Wen Tingyun’s ornate late Tang style, Feng’s work leans toward sparse elegance, yet conceals an undercurrent of dense emotional power.

Artistic Merits

- Layered Emotional Progression

From falling petals to the end of feasting, then ascending the tower to gaze afar, finally leaning on rails with hidden tears—emotions gradually focus inward. - Rich, Intertextual Imagery

Plum blossoms and snow, music and wine, cold peaks and wild geese, twilight and mist—each refracts emotion through multiple facets. - Masterful Contrasts

Spring mountains yet cold; sorrow thickens after revelry ends; blossoms contrast with parting—such juxtapositions heighten emotional tension. - Subtle Yet Potent

The language is refined, the emotions delicate, yet beneath the subtlety lies a profound lament for life’s transience.

Insights

This ci reminds us that beauty and togetherness are often fleeting, while loss and longing linger. Whether through scattering plum blossoms or geese vanishing into empty skies, it hints at life’s irreversible flow. It prompts reflection: in finite time, can we cherish the present more deeply? Simultaneously, the poem embodies literature’s power—using evocative scenery to elevate personal emotion into universal resonance, letting readers a millennium later still find their own heartache in falling petals and evening haze.

About the Poet

Feng Yansi (冯延巳 903 - 960), courtesy name Zhengzhong, was a native of Guangling (modern-day Yangzhou, Jiangsu) and a renowned ci poet of the Southern Tang during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. Rising to the position of Left Vice Director of the Department of State Affairs (Zuo Puye Tongping Zhangshi), he enjoyed the deep trust of Emperor Li Jing. His ci poetry forged a new path beyond the Huajian tradition, directly influencing later masters like Yan Shu and Ouyang Xiu, playing a pivotal role in the transition of ci from "entertainment for musicians" to "literary expression of scholar-officials."