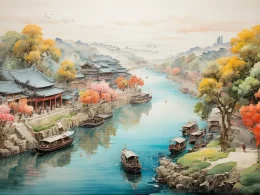

Today we roam along the Northern Pool;

Our boat ripples the water clear and cool.

The shimmering waves caress the willows tender.

Spring comes and goes year after year in splendor—

While silvery frost steals over our heads unseen.

Fair singers with their melodies serene!

How can we not get drunk in such an hour?

Fill up your golden cup, my friend, with wine!

E'en though spring revels may our health undermine,

To taste this joy is still a life divine.

Original Poem

「浪淘沙 · 今日北池游」

今日北池游。漾漾轻舟。

波光潋滟柳条柔。

如此春来春又去,白了人头。好妓好歌喉。不醉难休。

欧阳修

劝君满满酌金瓯。

纵使花时常病酒,也是风流。

Interpretation

Composed in 1045 amid the collapse of the Qingli Reforms, this lyric was written during Ouyang Xiu's double exile—first to Zhengding, then to Chuzhou—after his political allies Fan Zhongyan and Han Qi were purged. Beneath its surface revelry, the poem conceals the anguish of a reformer witnessing his ideals shattered, using spring's vitality to underscore human transience.

First Stanza: "今日北池游。漾漾轻舟。波光潋滟柳条柔。如此春来春又去,白了人头。"

Jīn rì běi chí yóu. Yàng yàng qīng zhōu. Bō guāng liàn yàn liǔ tiáo róu. Rú cǐ chūn lái chūn yòu qù, bái le rén tóu.

Today we drift on North Pond—

Ripples cradle our skiff.

Sun-dazzled waves, willow tendrils

Caress the air.

Thus springs arrive,

Thus springs depart,

Whitening our hair

With their indifferent care.

The stanza constructs a kinetic paradox: the boat's gentle rocking (漾漾) and willow's softness (柳条柔) belie the violent temporal undertow. "Whitening our hair" (白了人头) performs a visual pun—the white willow catkins mirroring the speaker's aged locks, nature's cyclical renewal underscoring human linear decay. The tone shifts imperceptibly from idyllic to elegiac, much like the failed reforms' trajectory.

Second Stanza: "好妓好歌喉。不醉难休。劝君满满酌金瓯。纵使花时常病酒,也是风流。"

Hǎo jì hǎo gē hóu. Bù zuì nán xiū. Quàn jūn mǎn mǎn zhuó jīn ōu. Zòng shǐ huā shí cháng bìng jiǔ, yě shì fēng liú.

Lovely courtesans,

Lovelier songs—

Without drunkenness,

No conclusion.

Fill your golden cup

To the brim, friend.

Even if spring's prime

Leaves us alcohol-sick,

Call it

Fengliu

Nonetheless.

Here, the "golden cup" (金瓯)—a vessel for state rituals—is repurposed for private anesthesia. The oxymoronic "alcohol-sick fengliu" (病酒风流) lays bare the scholar-official's dilemma: political failure can only be aestheticized, not cured. The courtesans' beauty becomes cruel counterpoint to the drinkers' despair, their songs the background score to a wake for stillborn reforms.

Holistic Appreciation

This lyric poem presents a spring outing on the surface while conveying deeper introspection beneath. The first stanza depicts the exuberance of springtime, with "white-haired head" metaphorically hinting at unfulfilled ambitions and the passage of youth. The second stanza shifts to the revelry of a banquet, yet this mirth thinly veils the poet’s political disillusionment and quiet melancholy. Though the language appears simple and the tone light, the poem carries profound emotional depth—its radiant imagery conceals a muted sorrow. Rather than lamenting his demotion outright, the poet weaves his feelings into natural scenes and everyday moments: the spring waters, willow branches, golden cups, and drunken demeanor. This embodies the quintessential Song lyric aesthetic—"mournful yet not despairing, beautiful yet not ostentatious."

Artistic Merits

The poem’s greatest strength lies in its ability to cloak profound grief in delicate charm and mask deep sentiment beneath a facade of ease. First, its structure fluidly transitions from a spring excursion to a drinking feast, shifting from brightness to subdued gloom. Second, it employs contrast—placing joyful scenes against inner desolation: "willow branches supple" juxtaposed with "white-haired head," and "fair singers, fair songs" against "drunken malaise and gallant airs." These contrasts poignantly capture the struggle to feign cheer amid dejection, seeking solace in intoxication. Third, the language is deceptively simple yet resonant. The phrase "white-haired head" (白了人头), seemingly plain, carries profound emotional weight, achieving subtlety and lingering depth without overt display. The poem exemplifies the introspective yet richly layered artistry of Song dynasty lyricists.

Insights

Beyond depicting the Song literati’s springtime leisure, the poem reflects the psychological coping mechanism of masking setbacks with "gallant airs" (风流) and drunken escapism. It reminds us that even in life’s disappointments, one may find solace in beauty; even self-mockery and inebriation can be dignified forms of endurance. The emotions conveyed by Ouyang Xiu epitomize the scholar-official’s plight—"harmonious in appearance, bitter at heart"—a sentiment that resonates across centuries. For modern readers, it offers not only an aesthetic revelation but also a mirror to the soul.

About the Poet

Ouyang Xiu (欧阳修, 1007 - 1072), a native of Yongfeng, Jizhou (present-day Jiangxi Province), emerged as the preeminent literary figure of the Northern Song Dynasty. After attaining the jinshi degree in 1030, he spearheaded a literary reform movement that rejected the ornate Xikun style prevalent at court. As a mentor who nurtured literary giants like Su Shi and Zeng Gong, he laid the foundation for the golden age of Northern Song literature. Recognized as one of the "Eight Great Prose Masters of Tang and Song," Ouyang stands as the pivotal figure in the transformation of Northern Song literary culture.