Can vernal winds not reach the ends of the earth?

In second moon no mountain flowers blow.

The branches bent with snow still bear oranges red,

And frozen thunder wakes the bamboo shoots below.

At night I hear wild geese returning north with spring;

Ill, I find objects changed with the new year.

Once a guest in peony-loving Luoyang town,

Why should I sigh for flowers late appearing here?

Original Poem

「戏答元珍」

欧阳修

春风疑不到天涯,二月山城未见花。

残雪压枝犹有橘,冻雷惊笋欲抽芽。

夜闻归雁生乡思,病入新年感物华。

曾是洛阳花下客,野芳虽晚不须嗟。

Interpretation

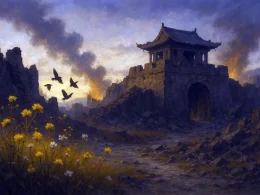

Composed in the spring of 1037 AD (the fourth year of Emperor Renzong's Jingyou era), this poem was written during Ouyang Xiu's second year of exile as magistrate of Yiling County (modern Yichang, Hubei). Having been banished from court during factional conflicts, he received a poem from his friend Ding Baochen lamenting the delayed spring blossoms in their mountainous region. Though titled "Playful Reply," the work transcends casual banter, weaving landscape observation with profound emotional resonance to reveal the poet's resilient spirit amidst adversity.

First Couplet: "春风疑不到天涯,二月山城未见花。"

Chūn fēng yí bù dào tiān yá, èr yuè shān chéng wèi jiàn huā.

Can spring winds never reach earth's farthest rim?

Our mountain town sees no blooms in second moon's dim.

The opening establishes temporal-spatial exile: "earth's farthest rim" (天涯) geographically marks the remote post while politically echoing the emperor's disregarded grace. The barren February landscape becomes a metaphor for the poet's isolated condition, with absent blossoms symbolizing forsaken court favor.

Second Couplet: "残雪压枝犹有橘,冻雷惊笋欲抽芽。"

Cán xuě yā zhī yóu yǒu jú, dòng léi jīng sǔn yù chōu yá.

Last snows weigh on branches where late oranges cling,

Frost-shocking thunder stirs bamboo shoots to spring.

Nature's paradoxes mirror the poet's complex state: the snowbound oranges embody endurance beyond season, while the subterranean bamboo's response to "frost-shocking thunder" (冻雷) captures latent vitality. These images construct a silent dialogue between surface desolation and hidden regeneration.

Third Couplet: "夜闻归雁生乡思,病入新年感物华。"

Yè wén guī yàn shēng xiāng sī, bìng rù xīn nián gǎn wù huá.

Night geese returning hatch my homeland dreams,

New year entered ailing—how time's splendor streams!

The migratory geese (归雁), traditional messengers of displacement, trigger layered nostalgia—for capital politics and literary circles. The bodily "ailing" (病) and temporal "new year" (新年) collide to measure spiritual exhaustion against time's relentless flow, achieving a metaphysical sigh.

Fourth Couplet: "曾是洛阳花下客,野芳虽晚不须嗟。"

Céng shì luò yáng huā xià kè, yě fāng suī wǎn bù xū jiē.

Once we reveled where Luoyang's peonies blaze,

Why mourn these wild blooms' delayed spring days?

The Luoyang peonies (洛阳花) symbolize past glory as capital intellectuals, making the mountain wildflowers (野芳) emblematic of current exile. The rhetorical "why mourn" (不须嗟) thinly veils profound lament, its very denial amplifying the unspeakable loss through classical restraint.

Holistic Appreciation

This poem unfolds against the backdrop of early spring scenery, transitioning seamlessly from depiction to introspection, making it both a landscape poem and a lyrical meditation. The opening couplet begins with a rhetorical question—"Why has the spring breeze not arrived?"—setting the thematic tone. The middle couplets vividly capture the unique spring sights of Yiling, portraying tangerine branches, lingering snow, distant thunder, and budding bamboo shoots in striking detail, composing a serene yet vibrant tableau. The final couplet shifts from scenery to personal reflection, contrasting the poet’s past in bustling Luoyang with the desolation of exile in Yiling. Though framed in a self-mocking "jest," the verse carries profound emotional weight.

The mood evolves from melancholy to resilience, while the structure fluidly progresses from observation to contemplation. Despite adversity, the poet meets his fate with equanimity, embodying the Confucian ideal of "remaining unbroken in hardship."

Artistic Merits

- Playful Title, Profound Undertones: The word "jest" (戏) in the title suggests lightheartedness, yet it serves as a literary veil—a means of self-consolation. Through this epistolary "reply," Ouyang Xiu transforms personal lament into a work of gentle yet penetrating emotional power.

- Rich Imagery, Exquisite Detail: The poem weaves together multiple natural motifs—spring breezes, unmelted snow, tangerines, thunder, bamboo shoots, and migrating geese—each alive with symbolic resonance. The delayed spring blossoms hint at withheld imperial favor; the geese evoke homesickness; the frozen thunder stirs hope. Scene and sentiment merge flawlessly.

- Lyrical Subtext, Subtle Depth: Without overt grievance, the poem channels emotion through nature’s minutiae: belated flowers, awakening shoots, and stubborn snow. It mourns without bitterness, protests without rancor, epitomizing the classical tradition where "feeling dwells within scenery, and scenery within feeling."

Insights

This poem reveals how an exiled scholar, though banished to the wilderness, channels his resilience into the quiet beauty of nature. It reminds us that even in adversity, one may find hope in winter’s last snow, tangerine-laden boughs, the rumble of spring thunder, or wildflowers pushing through the earth. Ouyang Xiu’s ethos—"grieving without wrath," "self-soothing without surrender"—exemplifies not just literary grace but a philosophy of steadfast composure, offering timeless guidance for navigating life’s lows with dignity and quiet strength.

Poem Translator

Xu Yuanchong(许渊冲)

About the Poet

Ouyang Xiu (欧阳修, 1007 - 1072), a native of Yongfeng, Jizhou (present-day Jiangxi Province), emerged as the preeminent literary figure of the Northern Song Dynasty. After attaining the jinshi degree in 1030, he spearheaded a literary reform movement that rejected the ornate Xikun style prevalent at court. As a mentor who nurtured literary giants like Su Shi and Zeng Gong, he laid the foundation for the golden age of Northern Song literature. Recognized as one of the "Eight Great Prose Masters of Tang and Song," Ouyang stands as the pivotal figure in the transformation of Northern Song literary culture.