A bell in the mountain-temple sounds the coming of night.

I hear people at the fishing-town stumble aboard the ferry,

While others follow the sand-bank to their homes along the river.

...I also take a boat and am bound for Lumen Mountain --

And soon the Lumen moonlight is piercing misty trees.

I have come, before I know it, upon an ancient hermitage,

The thatch door, the piney path, the solitude, the quiet,

Where a hermit lives and moves, never needing a companion.

Original Poem

「夜归鹿门歌」

孟浩然

山寺钟鸣昼已昏,渔梁渡头争渡喧。

人随沙路向江村,余亦乘舟归鹿门。

鹿门月照开烟树,忽到庞公栖隐处。

岩扉松径长寂寥,惟有幽人自来去。

Interpretation

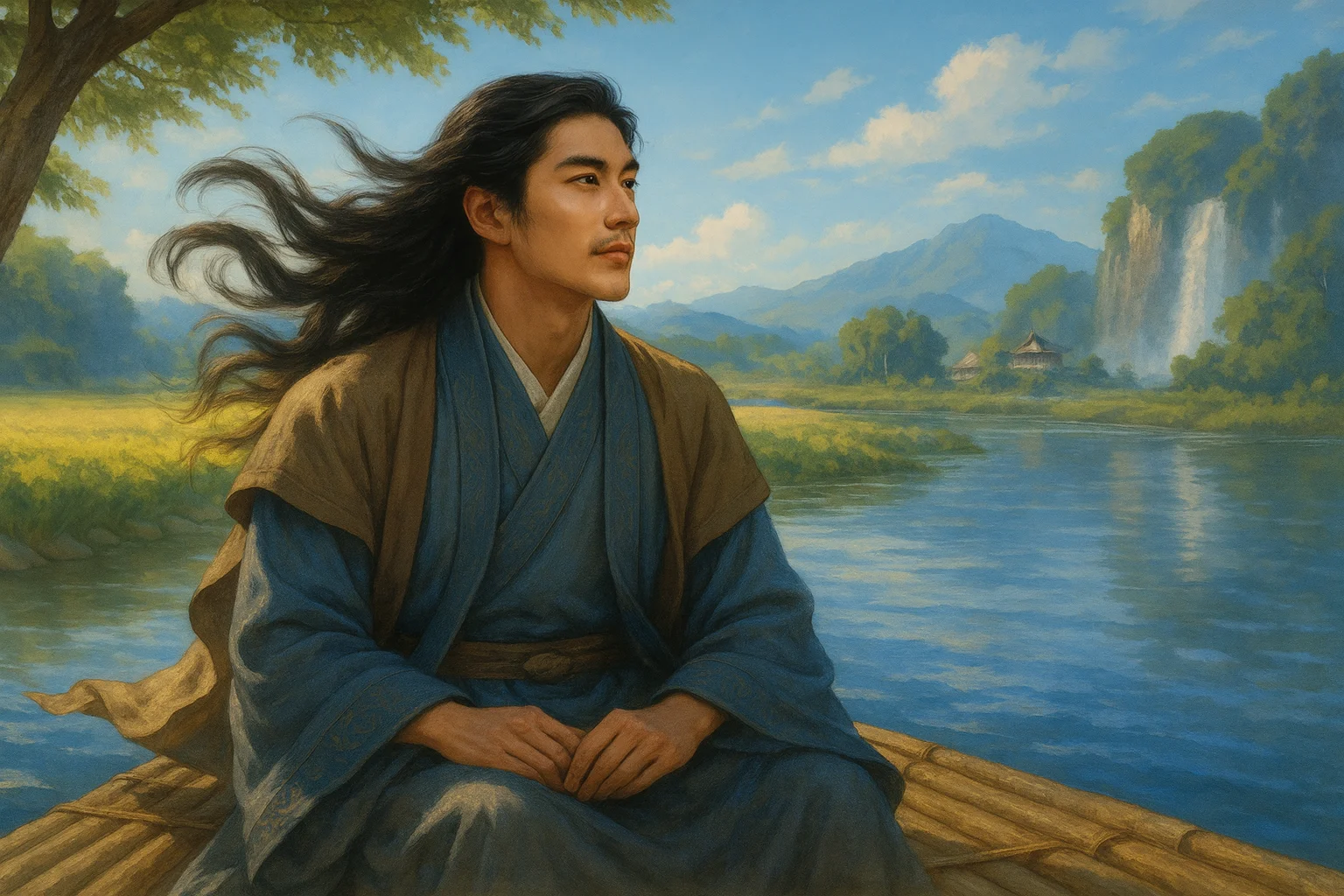

This poem was composed after 733 CE, during Meng Haoran's period of reclusion in Xiangyang following his return from Chang'an. His travels and pursuit of an official career before the age of forty had only yielded the desolation encapsulated in his other lines: "In silence, what is there to await? / Morning after morning, I return alone, forlorn." Having finally relinquished his obsession with worldly fame and status, he returned to his homeland. For him, Lumen Mountain was no longer merely a geographical site of seclusion; it became a symbol of spiritual rebirth.

Lumen Mountain lies southeast of Xiangyang. During the late Han dynasty, the esteemed scholar Pang Degong, refusing an official summons from the warlord Liu Biao, retreated to Lumen Mountain with his wife to gather medicinal herbs and never returned, leaving behind a celebrated tale of a lofty recluse. By "building a simple hut to dwell there for a time," Meng Haoran was, through action, completing his spiritual emulation of Pang Degong—marking a pivotal turn in his life's path from 'seeking usefulness in the world' to 'finding sufficiency within his own heart.' The "night journey" of the title is not a casual record of an evening outing, but a deliberately composed spiritual rite: he bids farewell to daylight in the gathering dusk, to the mundane world on the journey home, and, amidst the moonlight and soughing pines of Lumen Mountain, reclaims his own soul.

The poem presents two groups of "returnees": the crowd at the ferry "heads for the riverside village," while the poet alone "returns to Lumen Mountain." Their direction is the same, but their destinations are worlds apart. The riverside village represents the secular home; Lumen Mountain signifies the homeland of the spirit. This contrast, seemingly sketched with a light touch, in fact encapsulates the full tension between seclusion and prominence, the multitude and the solitary, the dusty world and transcendent freedom.

First Couplet: "山寺钟鸣昼已昏,渔梁渡头争渡喧。"

Shān sì zhōng míng zhòu yǐ hūn, Yúliáng dù tóu zhēng dù xuān.

The mountain temple's bells announce the dusk, day done; / At Yuliang Ferry, a clamor rises as folks scurry for the crossing, every one.

The poem opens by painting the twilight through sound: the bells from the mountain temple, distant and serene; the clamor rising from the ferry, urgent and chaotic. One is serene, the other clamorous; one distant, one near—they are juxtaposed within the same twilight yet remain distinctly separate. This is Meng Haoran's distinctive technique: he never deliberately criticizes the mundane world, but calmly presents two states of existence side by side, allowing the reader to discern for themselves where their own heart inclines. The phrase "clamor… for the crossing" is particularly skillful. The word "clamor" captures the urgency of ordinary people hurrying home at day's end, while subtly conveying the poet's own already-detached state of mind. He hears the noise, sees the bustle, but already stands apart. Physically present at the ferry, his heart has already boarded the boat—sailing toward a different destination.

Second Couplet: "人随沙路向江村,余亦乘舟归鹿门。"

Rén suí shā lù xiàng jiāng cūn, yú yì chéng zhōu guī Lùmén.

People follow the sandy path toward the riverside village; / I, too, board a boat, returning to Lumen Mountain.

This couplet serves as the pivotal hinge and marks the first appearance of the subjective "I" in the poem. The opening couplet was a panoramic sketch of dusk; here, the focus abruptly narrows, placing the poet himself at the center of the scene. Syntactically, it creates a parallel contrast: people return to the riverside village; I return to Lumen Mountain. The paths differ, the destinations are distinct, yet both involve a "returning."

The word "too" is profoundly evocative. It neither dismisses the validity of others' homeward paths nor elevates his own choice; it simply states a factual divergence with calm acceptance. Yet it is precisely this non-judgmental equanimity that renders the resoluteness of his reclusion more steadfast—true detachment does not require demeaning the worldly to prove itself. "Board a boat, returning to Lumen Mountain" describes the literal journey, but more significantly, it symbolizes the journey of the heart. Traveling by boat on the water, heading toward the mountains, moving from the clamorous ferry to the silent forest—this waterway perfectly externalizes the poet's entire spiritual trajectory from seeking office to embracing seclusion, from agitation to stillness, from the multitude to solitude.

Third Couplet: "鹿门月照开烟树,忽到庞公栖隐处。"

Lùmén yuè zhào kāi yān shù, hū dào Páng gōng qī yǐn chù.

Moonlight on Lumen Mountain pierces the haze-veiled trees; / Suddenly, I arrive at where Pang Gong found his ease.

This couplet marks a dual ingress into both space and state of mind. The boat reaches the mountain's foot; the poet enters the woods; night deepens; the moonlight brightens. "Pierces the haze-veiled trees" is exquisite—the moonlight, like water, washes open layer upon layer of mountain mist and tree shadows, revealing deep within the traces of that lofty scholar from centuries past. Most poignant are the words "suddenly arrive." It is not "search and find" or "deliberately visit," but arriving unconsciously, almost inadvertently. This indicates the poet's journey is not a deliberate pilgrimage; rather, his body and mind have already merged with this mountain forest. The journey home is itself the destination; arrival requires no conscious realization. Pang Gong's secluded dwelling lies deep in the mountains, yet it arrives unexpectedly amidst the poet's boat ride and the moonlight—true spiritual encounters never require deliberate seeking. In this moment, Meng Haoran and Pang Degong, separated by five centuries, under the same Lumen moon, attain the same stillness.

Fourth Couplet: "岩扉松径长寂寥,惟有幽人自来去。"

Yán fēi sōng jìng cháng jì liáo, wéi yǒu yōu rén zì lái qù.

The rocky gate, the pine-lined path—perpetual solitude reigns; / Here, only a man of seclusion comes and goes as he pleases.

The poem's ultimate realm unfolds here. "The rocky gate, the pine-lined path" refer to Pang Gong's former dwelling and also to Meng Haoran's present abode. "Perpetual solitude" is not a lament but a fulfillment—this solitude is precisely the barrier that preserves the recluse's essential self. A place the worldly eye might see as desolate and bleak becomes, under the poet's brush, a realm of perfect, self-sufficient freedom. The final line, "Here, only a man of seclusion comes and goes as he pleases," is the poetic core and the most serene confession. The "man of seclusion" is Pang Degong and also Meng Haoran himself; it is the image of a lofty scholar across the ages and the poet's self-affirmation in this very moment. "Comes and goes as he pleases" captures the entire essence of the eremitic life: no welcomes, no farewells, no attachments, no constraints, coming and going with the heart's desire, free from worldly strife.

The entire poem begins with "clamor" and ends with "solitude"; it opens with the multitude and closes with the recluse; it moves from the jostling at the ferry to the solitary journey into the mountains. This trajectory from movement to stillness, from the outer to the inner, from the many to the one, is precisely the complete rite of the poet's spiritual homecoming.

Overall Appreciation

This poem represents the pinnacle of Meng Haoran's reclusive poetry and is, in essence, the spiritual autobiography he wrote for himself. Using a single night journey as its narrative thread, it accomplishes a transcendent chronicle of the soul in every detail.

The poem's most distinctive feature lies in its simultaneous unfolding of two spaces: one, the geographical journey home from ferry to mountain forest; the other, the spiritual metamorphosis from the dusty world to transcendent freedom. These two spaces reflect and illuminate each other, transforming an ordinary night return into an eternal rite of the soul's homecoming.

The Lumen Mountain in the poem is no longer a mere geographical peak; it is the spiritual homeland Meng Haoran constructed for himself. Here, Pang Degong completed his rejection of secular power; here, Meng Haoran completed his release from the illusions of fame and achievement. Two generations of recluses, the same mountain forest, meet quietly in this poem across five centuries. This is no coincidence, but a tender leading-on by cultural memory—when one truly comprehends the choices of predecessors, one finds one's own place of return.

Artistic Features

- Contrast and Progression in Spatial Structure: The poem unfolds along two parallel spatial lines: "Ferry—Sandy Path—Riverside Village" and "Boat—Lumen Mountain—Rocky Gate." The former is the people's homeward path; the latter is the poet's. These lines progress from juxtaposition to divergence, finally separating completely, forming a clear spiritual altitude difference.

- Implicit Rendering of Temporal Consciousness: Not a word in the poem explicitly mentions past and present, yet through the "sudden" arrival at "where Pang Gong found his ease," five hundred years are compressed into a moment of enlightenment. This technique of implicit allusion makes the sense of history fall as naturally as moonlight, without a trace of artifice.

- Subtle Use of Personal Pronouns: From the impersonal, panoramic description of the opening couplet, to the first appearance of "I, too" in the second, to the self-identification as "a man of seclusion" in the final line, the poet completes a process of self-recognition progressing from concealment, to manifestation, to sublimation.

- Suspended Conclusion and Lingering Resonance: The poem concludes with "comes and goes as he pleases," offering no sequel or commentary. This open-ended closure allows the poetic realm to extend outward limitlessly—we do not know where the recluse will go, just as we need not ask whether Meng Haoran, after his reclusion, attained ultimate peace. The answer lies in the unspoken.

Insights

Lumen Mountain is not a towering peak, and Pang Degong's traces have long since vanished. Yet Meng Haoran granted this mountain eternal life through his poetry. Every era has its "ferry" and its "Lumen Mountain"—the former is the place we must go for livelihood; the latter is the shore our souls truly yearn to reach. Meng Haoran shows us: true reclusion need not involve fleeing deep into the mountains. It can be accomplished on a night-journey home, realized in the instant moonlight pierces haze-veiled trees, or can even occur quietly in the very moment of reading this poem.

"Here, only a man of seclusion comes and goes as he pleases"—these words are the recluse's self-portrait, and an invitation to all who desire spiritual freedom. They invite us, amidst the bustle of the worldly life, to preserve a quiet path leading to our own inner Lumen Mountain; to listen, while responding to countless external calls, also to the most authentic voice of that soul which "comes and goes as it pleases."

The Lumen moon of a millennium ago still shines on every night traveler willing to board the boat and return.

Poem translator

Kiang Kanghu

About the poet

Meng Haoran (孟浩然), 689 - 740 AD, a native of Xiangyang, Hubei, was a famous poet of the Sheng Tang Dynasty. With the exception of one trip to the north when he was in his forties, when he was seeking fame in Chang'an and Luoyang, he spent most of his life in seclusion in his hometown of Lumenshan or roaming around.