The Son of Heaven in Yuanhe times was martial as a god

And might be likened only to the Emperors Xuan and Xi.

He took an oath to reassert the glory of the empire,

And tribute was brought to his palace from all four quarters.

Western Huai for fifty years had been a bandit country,

Wolves becoming lynxes, lynxes becoming bears.

They assailed the mountains and rivers, rising from the plains,

With their long spears and sharp lances aimed at the Sun.

But the Emperor had a wise premier, by the name of Du,

Who, guarded by spirits against assassination,

Hong at his girdle the seal of state, and accepted chief command,

While these savage winds were harrying the flags of the Ruler of Heaven.

Generals Suo, Wu, Gu, and Tong became his paws and claws;

Civil and military experts brought their writingbrushes,

And his recording adviser was wise and resolute.

A hundred and forty thousand soldiers, fighting like lions and tigers,

Captured the bandit chieftains for the Imperial Temple.

So complete a victory was a supreme event;

And the Emperor said: "To you, Du, should go the highest honour,

And your secretary, Yu, should write a record of it."

When Yu had bowed his head, he leapt and danced, saying:

"Historical writings on stone and metal are my especial art;

And, since I know the finest brush-work of the old masters,

My duty in this instance is more than merely official,

And I should be at fault if I modestly declined."

The Emperor, on hearing this, nodded many times.

And Yu retired and fasted and, in a narrow workroom,

His great brush thick with ink as with drops of rain,

Chose characters like those in the Canons of Yao and Xun,

And a style as in the ancient poems Qingmiao and Shengmin.

And soon the description was ready, on a sheet of paper.

In the morning he laid it, with a bow, on the purple stairs.

He memorialized the throne: "I, unworthy,

Have dared to record this exploit, for a monument."

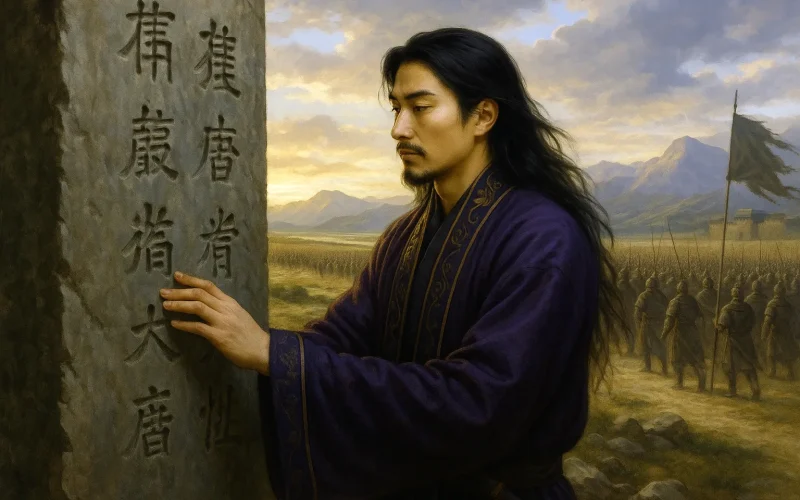

The tablet was thirty feet high, the characters large as dippers;

It was set on a sacred tortoise, its columns flanked with ragons...

The phrases were strange with deep words that few could understand;

And jealousy entered and malice and reached the Emperor --

So that a rope a hundred feet long pulled the tablet down

And coarse sand and small stones ground away its face.

But literature endures, like the universal spirit,

And its breath becomes a part of the vitals of all men.

The Tang plate, the Confucian tripod, are eternal things,

Not because of their forms, but because of their inscriptions...

Sagacious is our sovereign and wise his minister,

And high their successes and prosperous their reign;

But unless it be recorded by a writing such as this,

How may they hope to rival the three and five good rulers?

I wish I could write ten thousand copies to read ten thousand times,

Till spittle ran from my lips and calluses hardened my fingers,

And still could hand them down, through seventy-two generations,

As corner-stones for Rooms of Great Deeds on the Sacred Mountains.

Original Poem

「韩碑」

李商隐

元和天子神武姿, 彼何人哉轩与羲,

誓将上雪列圣耻, 坐法宫中朝四夷。

淮西有贼五十载, 封狼生貙貙生罴;

不据山河据平地, 长戈利矛日可麾。

帝得圣相相曰度, 贼斫不死神扶持。

腰悬相印作都统, 阴风惨澹天王旗。

愬武古通作牙爪, 仪曹外郎载笔随。

行军司马智且勇, 十四万众犹虎貔。

入蔡缚贼献太庙。 功无与让恩不訾。

帝曰汝度功第一, 汝从事愈宜为辞。

愈拜稽首蹈且舞, 金石刻画臣能为。

古者世称大手笔, 此事不系于职司。

当仁自古有不让, 言讫屡颔天子颐。

公退斋戒坐小阁, 濡染大笔何淋漓。

点窜尧典舜典字, 涂改清庙生民诗。

文成破体书在纸, 清晨再拜铺丹墀。

表曰臣愈昧死上, 咏神圣功书之碑。

碑高三丈字如斗, 负以灵鳌蟠以螭。

句奇语重喻者少, 谗之天子言其私。

长绳百尺拽碑倒。 粗沙大石相磨治。

公之斯文若元气, 先时已入人肝脾。

汤盘孔鼎有述作, 今无其器存其辞。

呜呼圣皇及圣相, 相与烜赫流淳熙。

公之斯文不示后, 曷与三五相攀追?

愿书万本诵万过, 口角流沫右手胝;

传之七十有二代, 以为封禅玉检明堂基。

Interpretation

This poem was composed during the late Tang dynasty, with Li Shangyin using "Han Monument" as his title to narrate the historical event of Han Yu composing the "Pacification of Huaixi Stele" and its subsequent destruction. In the twelfth year of Yuanhe (817), under Chancellor Pei Du's strategy, Emperor Xianzong of Tang successfully suppressed the Huaixi rebellion led by Wu Yuanji through General Li Su's efforts, then commissioned Han Yu to compose the stele to commemorate this achievement. However, as the inscription emphasized Pei Du's contributions over Li Su's, it incurred the latter family's displeasure and was ultimately destroyed. Through this incident, Li Shangyin expresses indignation at loyal ministers being slandered and literary talents being slighted, while demonstrating the eternal spiritual value of Han's stele through poetic form.

Tenth Couplet: "帝曰汝度功第一,汝从事愈宜为辞。"

Dì yuē rǔ Dù gōng dìyī, rǔ cóngshì Yù yí wéi cí.

"The Emperor declared: 'Du, your merit stands foremost, Your subordinate Yu shall compose the text august.'"

The imperial decree formally recognizes Pei Du's primary role while entrusting Han Yu with literary commemoration, establishing the stele's official sanction.

Eleventh Couplet: "愈拜稽首蹈且舞,金石刻画臣能为。"

Yù bài qǐshǒu dǎo qiě wǔ, jīnshí kèhuà chén néng wéi.

"Yu kowtowed, then danced in solemn state, 'On metal and stone I'll engrave our great fate.'"

Han Yu's ceremonial response blends ritual propriety with artistic confidence, his dance embodying the gravity of this historiographic mission.

Twelfth Couplet: "古者世称大手笔,此事不系于职司。"

Gǔ zhě shì chēng dà shǒubǐ, cǐ shì bù xì yú zhísī.

"Antiquity honors monumental scribes, Such work transcends bureaucratic tribes."

Asserts the transcendence of true literary artistry above mere official duty, positioning Han Yu within China's great historiographic tradition.

Thirteenth Couplet: "当仁自古有不让,言讫屡颔天子颐。"

Dāng rén zìgǔ yǒu bù ràng, yán qì lǚ hàn tiānzǐ yí.

"'The worthy never decline when called,' The Emperor nodded as this truth was installed."

Captures the moment of imperial-literary covenant, where principled acceptance meets sovereign approval.

Fourteenth Couplet: "公退斋戒坐小阁,濡染大笔何淋漓。"

Gōng tuì zhāijiè zuò xiǎo gé, rú rǎn dà bǐ hé línlí.

"Retiring to fast in his studio's space, His great brush dripped with heaven-sent grace."

Depicts the sacred creative process - the writer's purification ritual yielding divinely inspired calligraphy.

Fifteenth Couplet: "点窜尧典舜典字,涂改清庙生民诗。"

Diǎn cuàn Yáo diǎn Shùn diǎn zì, tú gǎi qīng miào shēng mín shī.

"He edited phrases from Yao and Shun's scrolls, Revised temple hymns that chronicle souls."

The composition's grandeur surpasses even Confucian classics, claiming equal canonical status.

Sixteenth Couplet: "文成破体书在纸,清晨再拜铺丹墀。"

Wén chéng pò tǐ shū zài zhǐ, qīngchén zài bài pū dān chí.

"The text achieved - its form boldly new, At dawn presented on vermilion avenue."

The innovative inscription receives ceremonial presentation, its stylistic breakthrough matching its historical significance.

Seventeenth Couplet: "表曰臣愈昧死上,咏神圣功书之碑。"

Biǎo yuē chén Yù mèi sǐ shàng, yǒng shénshèng gōng shū zhī bēi.

"His memorial stated: 'Risking death I proclaim, These divine deeds demand eternal fame.'"

Han Yu's courageous dedication to historical truth outweighs personal safety concerns.

Eighteenth Couplet: "碑高三丈字如斗,负以灵鳌蟠以螭。"

Bēi gāo sān zhàng zì rú dǒu, fù yǐ líng áo pán yǐ chī.

"Three-zhang high with character-large might, Borne by sacred turtle, dragon-patterned bright."

The stele's physical grandeur matches its textual majesty, its mythological creatures symbolizing imperial legitimacy.

Nineteenth Couplet: "句奇语重喻者少,谗之天子言其私。"

Jù qí yǔ zhòng yù zhě shǎo, chán zhī tiānzǐ yán qí sī.

"Its profound lines few could construe, Slanderers whispered: 'He favors his crew.'"

The tragedy of literary excellence misunderstood and maliciously politicized.

Twentieth Couplet: "长绳百尺拽碑倒,粗沙大石相磨治。"

Cháng shéng bǎi chǐ zhuài bēi dǎo, cū shā dà shí xiāng mó zhì.

"With hundred-foot ropes they felled the stone, Coarse grindstones erased what history had shown."

The violent destruction scene underscores historical revisionism's brutality.

Twenty-first Couplet: "公之斯文若元气,先时已入人肝脾。"

Gōng zhī sī wén ruò yuánqì, xiān shí yǐ rù rén gān pí.

"Your words contain cosmic primal breath, Already etched in souls beyond death."

Affirms literature's spiritual immortality that transcends material destruction.

Twenty-second Couplet: "汤盘孔鼎有述作,今无其器存其辞。"

Tāng pán Kǒng dǐng yǒu shù zuò, jīn wú qí qì cún qí cí.

"Tang's basin and Confucius' tripod are no more, But their inscriptions time cannot ignore."

Historical precedents prove how words outlast their physical vessels.

Twenty-third Couplet: "呜呼圣皇及圣相,相与烜赫流淳熙。"

Wūhū shèng huáng jí shèng xiàng, xiāng yǔ xuǎn hè liú chún xī.

"Alas! The sage ruler and minister's light, Should have shone through ages clear and bright."

Laments the historical injustice done to these exemplary figures' deserved legacy.

Twenty-fourth Couplet: "公之斯文不示后,曷与三五相攀追?"

Gōng zhī sī wén bù shì hòu, hé yǔ sān wǔ xiāng pān zhuī?

"If this text won't guide posterity's hand, How compare with Three and Five Sovereigns grand?"

Rhetorically questions how future generations can access historical truth without such records.

Twenty-fifth Couplet: "愿书万本诵万过,口角流沫右手胝。"

Yuàn shū wàn běn sòng wàn guò, kǒu jiǎo liú mò yòu shǒu zhī.

"I'd copy ten thousand, recite each line, Till lips foam and right hand bears callous sign."

The poet's physical commitment to preserving cultural memory against erasure.

Twenty-sixth Couplet: "传之七十有二代,以为封禅玉检明堂基。"

Chuán zhī qīshí yǒu èr dài, yǐ wéi fēng shàn yù jiǎn míng táng jī.

"Transmit through seventy-two imperial reigns, As Fengshan's jade-seal and Mingtang's foundation stones."

Elevates the text to eternal ritual standard, ensuring its survival through dynastic cycles.

Overall Appreciation

"Han Stele" demonstrates meticulous structure with clear progression and majestic momentum. Li Shangyin uses Han Yu's stele as focal point, systematically detailing: the Huaixi campaign's background; Pei Du and Li Su's contributions; the stele's composition; and its eventual destruction. The poem extols emperor and ministers while lamenting loyalists slandered, revealing through the stele's fate the court's factional intrigues. This masterful integration of historical narrative and political commentary achieves remarkable depth.

Writing Characteristics

- Innovative poetic form: The seven-character ancient verse combines Han Yu's prose style with stele monumentality, creating unique rhythmic power.

- Strategic rhyme schemes: Calculated use of oblique tones produces forceful cadences that enhance the majestic atmosphere.

- Layered meanings: While ostensibly praising the stele, it subtly critiques political factionalism, blending historical documentation with sharp commentary.

- Vivid imagery: Military and literary depictions alternate to create compelling visual and intellectual impact.

Insights

Beyond commemorating the Huaixi victory, "Han Monument" exposes the perennial tragedy of merit unrecognized and justice subverted. The physical stele's destruction paradoxically confirms the immortality of true words, as Li Shangyin asserts: "Should this writing not endure, how compare with ancient sage-kings?" The poem affirms literature's power to transcend political oppression while warning against historical distortion. Its most profound lesson lies in affirming that while monuments may be toppled, truth ultimately withstands time's erosion.

Poem translator

Kiang Kanghu

About the poet

Li Shangyin (李商隐), 813 - 858 AD, was a great poet of the late Tang Dynasty. His poems were on a par with those of Du Mu, and he was known as "Little Li Du". Li Shangyin was a native of Qinyang, Jiaozuo City, Henan Province. When he was a teenager, he lost his father at the age of nine, and was called "Zheshui East and West, half a century of wandering".