The Great Canal was blamed for the Sui Empire's fall,

But on its waves the goods and food are brought to all.

Could the flood-fighting emperor do anything more

Than the Sui dragon-boats of three stories or four?

Original Poem

「汴河怀古 · 其二」

皮日休

尽道隋亡为此河,至今千里赖通波。

若无水殿龙舟事,共禹论功不较多。

Interpretation

This poem presents Pi Rixiu’s bold reappraisal of Emperor Yang of the Sui Dynasty’s construction of the Grand Canal. Though the emperor’s extravagance led to his downfall, the canal itself became an enduring boon to later generations. With a historian’s detachment, the poet weighs the mixed legacy of this colossal project, revealing both critical insight and philosophical depth.

First Couplet: "尽道隋亡为此河,至今千里赖通波。"

*"All blame the Sui’s fall on this river’s birth,

Yet still its waves link a thousand *li* of earth."*

The opening couplet overturns conventional wisdom. While the first line acknowledges popular condemnation of the canal as the Sui Dynasty’s ruin, the second counters with its lasting utility—the word "赖" (rely upon) underscoring the poet’s unflinching pragmatism. The flowing rhythm mirrors the canal’s unbroken course through history.

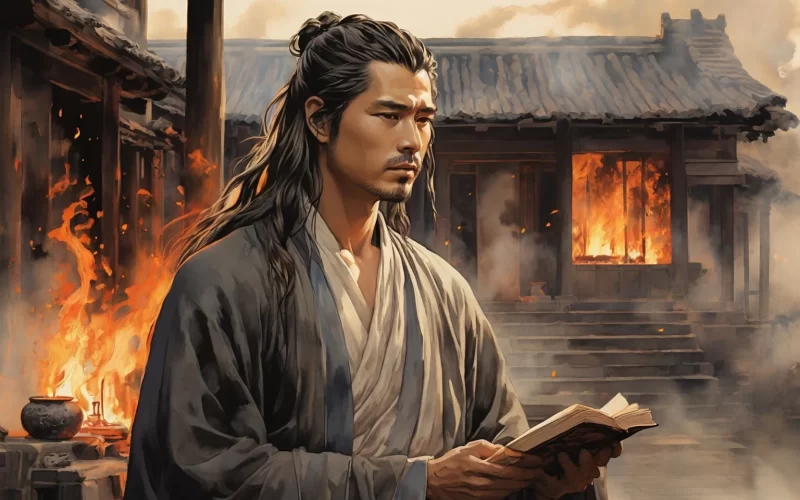

Second Couplet: "若无水殿龙舟事,共禹论功不较多。"

"Had those dragon boats and floating halls not been, His deeds might rival Yu the Great’s, unseen."

Here, Pi Rixiu employs razor-sharp irony. By hypothetically comparing Emperor Yang to Yu the Great—the legendary tamer of floods—he highlights how wanton luxury (水殿龙舟) drowned the ruler’s potential legacy. The juxtaposition is devastating: where Yu sacrificed for the people, Yang indulged at their expense. The couplet’s apparent praise thinly veils scathing critique.

Artistic Merits

The poem's most striking artistic feature lies in its ingenious subversion of historical narratives and its nuanced critique through seemingly neutral language. The poet masterfully employs rhetorical questions and hypothetical scenarios, using contrast to simultaneously affirm the Grand Canal's enduring benefits while exposing Emperor Yang's extravagant excesses that doomed his reign. This achieves a unified expression of commentary and lyricism, criticism and reflection. With concise yet profound language, its satirical edge remains subtly veiled, showcasing the late Tang poets' acute historical awareness and independent moral judgment.

Holistic Appreciation

Pi Rixiu re-examines Emperor Yang's construction of the Grand Canal through this innovative historical reassessment. While acknowledging the canal's monumental contributions to posterity, the poet never relents in condemning the emperor's tyrannical extravagance that precipitated dynastic collapse. The pivotal line "were it not for those dragon boats and water palaces" serves as both pointed satire and sober historical analysis. Between the lines emerges a warning to rulers: governance that neglects the people's welfare, despite temporary achievements, will ultimately face history's condemnation. This fusion of historical revisionism and indirect critique achieves a delicate balance between intellectual discourse and artistic expression, making it a masterpiece of late Tang historical poetry.

Insights

Using the dual legacy of Emperor Yang's Grand Canal, the poem reveals history's inherent complexity and multidimensionality. Though the canal benefited future generations, the emperor's cruelty and decadence caused national tragedy. Through contrast and hypothesis, the poet reminds us: rulers who exploit public resources for personal gratification ultimately pay a dire price. Historical accomplishments require popular support—only by prioritizing people's welfare can governance truly benefit the world and earn enduring recognition.ty and duality of historical events. The Grand Canal, though a monumental achievement that benefited later generations, was marred by the emperor's oppressive policies and extravagant lifestyle, ultimately leading to the dynasty’s demise. Pi Rixiu’s work reminds us that leadership requires a delicate balance between ambition and responsibility. A ruler’s legacy is judged not only by accomplishments but also by their treatment of the people. This enduring lesson cautions against the misuse of power and the neglect of civic welfare, highlighting the timeless importance of ethical governance.

Poem translator

Xu Yuanchong (许渊冲)

About the poet

Pi Rixiu (皮日休, c. 834-883), a Late Tang dynasty poet and scholar from Xiangyang, Hubei. He obtained the jinshi degree in 867 (8th year of Xiantong era). His poetry carried on Bai Juyi's New Yuefu tradition. After the failed uprising, he was presumably executed, with most of his works lost. The Complete Tang Poems preserves over 300 of his poems.