In the small yard, east of grapevine moon-rack,

My waist dances wild to drums' heroic beat.

Poems done, colored brushes share the verse—

Amid gold hairpins, I take my seat.

Autumn leaves chant cold in roaring wind,

Evening woods glow through sun's crystal rays.

If I wore Chuzhou's seal at my waist,

Surely they'd call me "Drunken Sage" these days.

Original Poem

「醉中偶成」

刘过

小院蒲萄月架东,舞腰忙趁鼓声雄。

诗成彩笔分题后,人在金钗财令中。

秋叶冷吟风浩荡,晚林烘透日玲珑。

腰间若佩滁州印,定有人呼作醉翁。

Interpretation

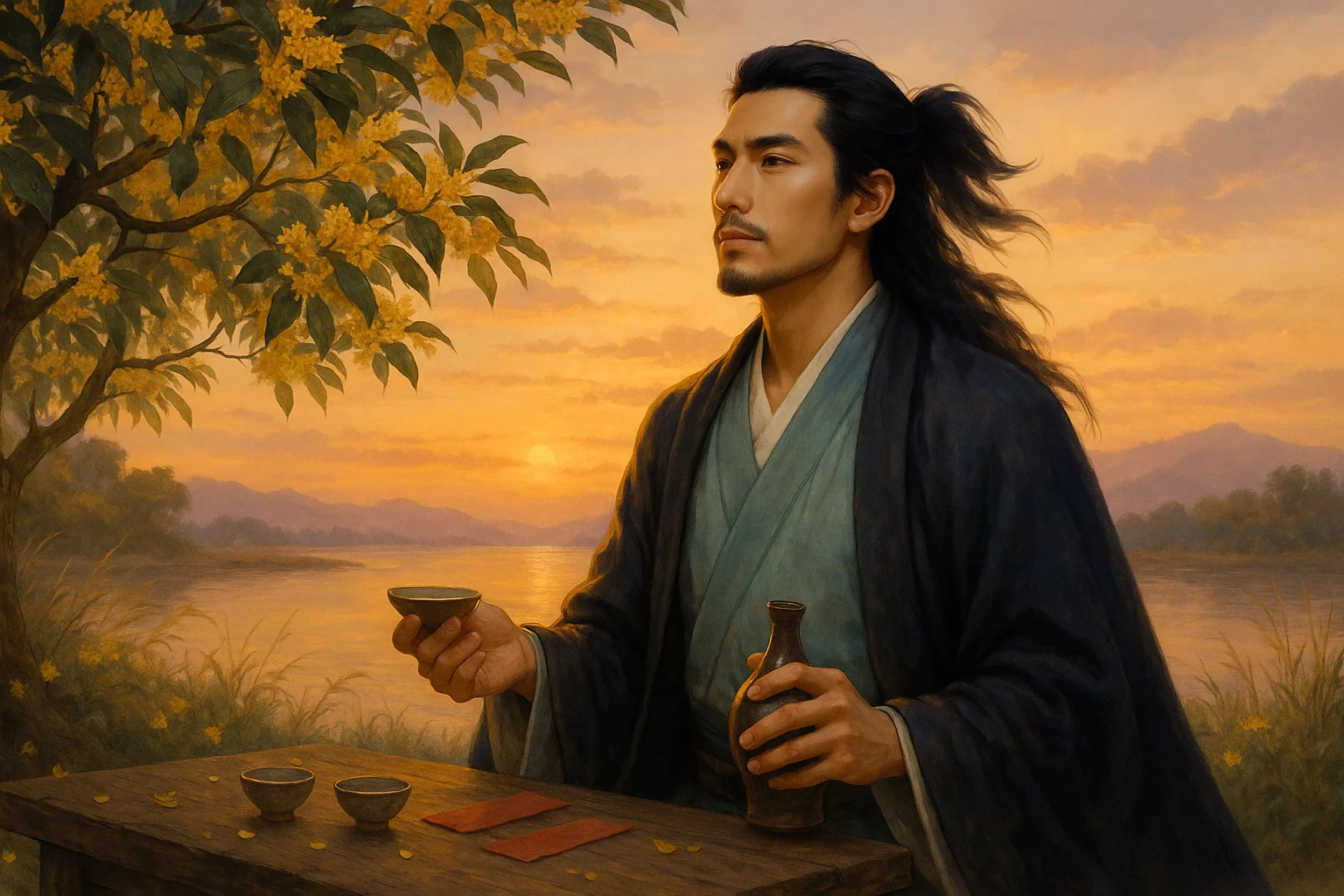

Composed in Liu Guo's later years during his wandering life beyond the circles of power, this poem emerges from a state of drunken spontaneity. Beneath its seemingly carefree tone lies profound contemplation—juxtaposing lively banquet scenes ("dancing waists," "golden hairpins") with autumnal melancholy ("cold-chanting leaves," "ignited woods"). The allusion to Ouyang Xiu's "Drunken Elder" persona reflects Liu's self-redefinition: though politically unfulfilled, he finds solace in poetry and wine. More than a tipsy improvisation, this work embodies a scholar's sober self-reckoning through intoxicated verse.

First Couplet: "小院蒲萄月架东,舞腰忙趁鼓声雄。"

Xiǎo yuàn pú táo yuè jià dōng, wǔ yāo máng chèn gǔ shēng xióng.

In the courtyard,

moonlit grapevines

trellised eastward—

dancing waists whirl

to drums' commanding roar.

Liu paints sensory contrast: static "moonlit vines" (蒲萄月架) frame kinetic "whirling waists" (舞腰忙趁). The drums' "commanding roar" (鼓声雄) suggests societal pressures beneath festive surfaces, foreshadowing the poem's tension between revelry and reflection.

Second Couplet: "诗成彩笔分题后,人在金钗财令中。"

Shī chéng cǎi bǐ fēn tí hòu, rén zài jīn chāi cái lìng zhōng.

Verse done,

my colored brush rests—

while I remain trapped

amid golden hairpins

and wealth's command.

Creative freedom ("colored brush rests") clashes with worldly entrapment ("golden hairpins, wealth's command"). The couplet's pivot—from artistic completion to social confinement—mirrors Liu's lifelong struggle between poetic ideals and political realities.

Third Couplet: "秋叶冷吟风浩荡,晚林烘透日玲珑。"

Qiū yè lěng yín fēng hào dàng, wǎn lín hōng tòu rì líng lóng.

Autumn leaves

chant cold

through vast winds—

sunset woods ignite

with luminous light.

Nature's voice emerges. "Cold-chanting leaves" (秋叶冷吟) personifies seasonal decay as poetic lament, while "ignited woods" (烘透日玲珑) transforms dying light into transcendental radiance—a fleeting epiphany in gathering darkness.

Fourth Couplet: "腰间若佩滁州印,定有人呼作醉翁。"

Yāo jiān ruò pèi chú zhōu yìn, dìng yǒu rén hū zuò zuì wēng.

Were Chuzhou's seal

to hang from my waist,

all would hail me

as the Drunken Elder

reborn.

The finale channels Ouyang Xiu's legacy. "Chuzhou's seal" (滁州印) symbolizes administrative power Liu never attained, while "Drunken Elder" (醉翁) reclaims dignity through literary immortality—turning political absence into cultural presence.

Holistic Appreciation

This introspective lyric poem employs drunkenness as a narrative device, unfolding the poet's observations, reflections, and emotions in layered progression—from lively scenes to inner contemplation, from poetic creation to life's meditations. The work evolves through subtle transformations, achieving remarkable fluidity.

The poem masterfully blends scene and sentiment. Its first half depicts tangible landscapes: moonlit grapevines, dancing girls and drumbeats—images rich with visual immediacy and vibrant life. The latter half turns inward: after completing his verse, the poet finds himself mired in the worldly muck of wealth and power, compelled to examine human affairs. Through autumn winds, falling leaves and twilight woods, he establishes a meditative atmosphere, ultimately adopting the persona of the "Drunken Elder." This reveals his yearning for carefree existence while acknowledging inescapable worldly entanglements. The line "Were Chuzhou's seal to hang from my waist, all would hail me as the Drunken Elder reborn" proves particularly profound—its surface humor and wit masking bitter self-comfort, articulating the poet's complex psyche: ambitious yet officially unrecognized, finding solace only in intoxication. This technique of drowning sorrow in wine while smiling through tears adds historical depth to the poem, elevating it beyond mere personal expression.

Artistic Merits

- Interwoven Scenes and Sentiments, Blending Reality and Imagination

The poem intricately depicts both physical landscapes and psychological depths, seamlessly alternating between external reality and internal contemplation. This creates a tightly-knit structure with fluid emotional transitions. - Self-Deprecating Allusions Bridging Elegance and Vernacular

References like "Chuzhou's seal" and "Drunken Elder" originate from Ouyang Xiu's legacy. By incorporating these into his self-portrayal, the poet expresses reverence while adding subtle self-mockery, establishing an emotional dialogue across historical periods. - Natural Language with Lively Rhythm

The poem employs unpretentious yet rhythmic phrasing that captures everyday scenes without sacrificing wit or literary flair. Its cadence flows melodiously, offering both aural pleasure and intellectual stimulation.

Insights

Liu's poem reveals how literary personas outlast political titles. The "Drunken Elder" transcends its historical origin (Ouyang Xiu) to become an archetype—allowing marginalized scholars like Liu to claim legitimacy through cultural continuity rather than official recognition.

For modern readers, the work models transforming constraint into creative fuel: Liu's "entrapment amid golden hairpins" mirrors our struggles in commercialized societies, while his "cold-chanting leaves" suggest finding voice in abandonment. The finale's brilliance lies in its imagined triumph—proving that sometimes, the most powerful identities are those we dare to envision for ourselves.

Ultimately, the poem suggests that true authority comes not from seals worn at the waist but from verses that outlive their makers. Liu's "Drunken Elder" stands eternal reminder: when reality denies us roles, art grants us rebirth.

About the Poet

Liu Guo (刘过 1154 - 1206), a native of Taihe in Jiangxi, was a ci poet of the Bold and Unconstrained School (haofang pai) during the Southern Song Dynasty. Though he remained a commoner all his life, wandering the rivers and lakes, he associated with literary giants like Lu You and Xin Qiji. His ci poetry is impassioned and heroic, and his verse is vigorous and forceful. Stylistically close to Xin Qiji but even more unrestrained, Liu Guo became a central figure among Xin’s poetic followers.