A wanderer hears drums portending battle.

By the first call of autumn from a wildgoose at the border,

He knows that the dews tonight will be frost.

...How much brighter the moonlight is at home!

O my brothers, lost and scattered,

What is life to me without you?

Yet if missives in time of peace go wrong --

What can I hope for during war?

Original Poem

「月夜忆舍弟」

杜甫

戍鼓断人行,秋边一雁声。

露从今夜白,月是故乡明。

有弟皆分散,无家问死生。

寄书长不达,况乃未休兵。

Interpretation

This poem was composed in the autumn of 759 CE, the second year of the Qianyuan era under Emperor Suzong, during Du Fu's displacement in Qinzhou. The An Lushan Rebellion continued unabated, famine plagued the Guanzhong region, and the poet, wandering with his family, faced dire hardship. As the war raged, his younger brothers were scattered across Henan and Shandong, with all communication severed and their fates unknown. On a solitary autumn night as the first chill dew descended, the poet gazed at the moon, longing for his distant kin. In this work, he fused his anxiety for the nation, his personal sorrow, and his deep fraternal longing into verse where every word bears profound grief and every line is imbued with poignant emotion.

First Couplet: 戍鼓断人行,秋边一雁声。

Shù gǔ duàn rén xíng, qiū biān yī yàn shēng.

The garrison drum cuts off the travelers' way; / A lone wild goose cries o'er the autumn border grey.

The opening is steeped in the atmosphere of a troubled age. The "garrison drum" signals ongoing conflict; the phrase "cuts off the travelers' way" conveys both the harshness of the curfew and the complete blockage of all roads. Then, the "lone wild goose cries" pierces the silence—a sound that marks the season and also serves as a metaphor for the poet's own displacement and for his scattered brothers, like a solitary bird severed from its flock. The heavy drumbeat and the desolate cry weave together, visually and aurally, casting a shroud of desolate border-autumn loneliness and the poet's own inner solitude over the entire poem.

Second Couplet: 露从今夜白,月是故乡明。

Lù cóng jīn yè bái, yuè shì gùxiāng míng.

From tonight on, the dew is seen to turn to frost; / The moon at home is brighter still, though tempests toss'd.

This couplet is the soul of the poem. "From tonight on, the dew is seen to turn to frost" aligns with the solar term (White Dew) while subtly implying the bleakness of the times and the chilling harshness of life. "The moon at home is brighter still" is not an objective comparison but a psychological truth—in the wanderer's heart, everything associated with home possesses a special, heightened radiance. The poet masterfully merges universal natural phenomena (frost-forming dew, a bright moon) with his personal, lived experience (longing for home, remembering his brothers), creating an emotional resonance that transcends time and space, securing its place as an immortal line.

Third Couplet: 有弟皆分散,无家问死生。

Yǒu dì jiē fēnsàn, wú jiā wèn sǐshēng.

I have my brothers, yet we're scattered, each one fled; / No home remains to ask if they are live or dead.

The focus shifts from imagery to a direct, heartfelt utterance. The language is starkly plain, the emotion profoundly heavy. The phrase "we're scattered" lays bare the cruel fragmentation of an ordinary family by war. The two words "no home remains" are written in blood and tears; they signify not merely the physical impossibility of return, but the dual loss of kinship as an emotional anchor and of a homestead as life's ultimate sanctuary. The dispersal of brothers is tragic in itself, yet the added anguish of being "unable to ask if they are alive or dead" makes the powerlessness of human existence—adrift like rootless tumbleweed in a chaotic age—utterly palpable within these ten stark characters.

Fourth Couplet: 寄书长不达,况乃未休兵。

Jì shū cháng bù dá, kuàng nǎi wèi xiū bīng.

The letters that I send can never get there, it appears; / How much more now, when warfare has raged on for years!

The final couplet employs a climactic technique to intensify the lament. "Can never get there" captures the personal dilemma of severed communication, while "warfare has raged on" names the tragic root of the entire era. The conjunction "how much more" connects the seemingly insignificant fate of the individual to the grand, relentless narrative of history. It lays bare the shared destiny of ruptured familial bonds and rootless longing under the shadow of endless war. Here, the private sorrow of remembering his brothers is wholly fused with a vast, collective grief for the suffering of the age.

Holistic Appreciation

Using "remembering my brothers" as its emotional core and the "moonlit night" as its spatio-temporal frame, this poem unfolds layer by layer like a portrait of longing for kin on an autumn night in a war-torn age. The four couplets follow a tight emotional logic: the first establishes a desolate atmosphere with border sounds and a goose's cry; the second uses seasonal imagery and moonlight to pinpoint the heart of homesickness; the third directly voices the pain of scattered brothers and a ruined homeland; the fourth concludes with the stark reality of impassable communication and unceasing warfare.

Here, Du Fu reveals another facet of his deeply poignant and powerfully controlled style. Without relying on startling imagery or ornate diction, but solely through plain descriptive language, internal emotional progression, and profound psychological truth, he constructs a deeply moving artistic world. The line "The moon at home is brighter still" has, through its unadorned simplicity and eternal emotional authenticity, transcended its specific historical context to become one of the quintessential expressions of nostalgia in the cultural psyche of the Chinese nation.

Artistic Merits

- Condensed Imagery, Profound Emotion within Scene

The imagery—"garrison drum," "wild goose's cry," "frost-forming dew," "bright moon"—is entirely commonplace, yet forged in the crucible of the poet's emotion, it becomes emblematic of a chaotic autumn and a homesick night, bearing the heavy sorrow of the era and the poet's personal anguish. - Precise Parallelism with Unimpeded Vitality

The second couplet, "From tonight on, the dew is seen to turn to frost; / The moon at home is brighter still," is formally perfectly parallel, yet the emotion within flows unimpeded. It possesses the formal beauty of regulated verse while containing the emotional tension of ancient-style poetry, showcasing Du Fu's superb skill in "infusing the ancient style into regulated verse." - Plain Diction, Profound Sincerity

The poem uses no obscure characters. Lines like "I have my brothers, yet we're scattered… / No home remains…" are almost colloquial, yet within their plain narration lies immense emotional force, achieving the artistic pinnacle where "the deepest feeling needs no ornament" to move readers profoundly. - Structurally Progressive, with a Vast, Resonant Conclusion

Moving from atmospheric description to emotional expression, from stating the present condition to probing its cause, the four couplets advance step by step. The final line, "How much more now, when warfare has raged on for years!" points to the root cause while leaving behind boundless lament, its resonance lingering like the toll of an autumn night bell.

Insights

This work reveals how, amid the cataclysmic fractures of history and the rending violence of war, the most elemental human emotions—care for kin, longing for home—become essential anchors that steady the individual against the void and affirm the very will to exist. Du Fu’s lament does not belong to him alone; it echoes in every soul set adrift by the storms of their age. In giving voice to this shared fragility, his poetry transcends private sorrow and becomes a lasting testament to our common humanity—a thread of tenderness that runs through the coarse fabric of time, reminding us that even in brokenness, we are bound by what and whom we cherish. Thus, what began as one poet’s midnight reflection endures as a quiet, resilient note in the collective memory of all who have loved and lost, and still dare to remember.

The poem reveals that in an age of uncertainty, kinship and memory are our final homeland. Even if the body drifts like tumbleweed and communication is severed, as long as the heart holds fast to the belief that "The moon at home is brighter still," one can preserve human warmth and a spiritual path home within the desolation. With his profound fraternal longing, Du Fu bequeaths to us an eternal poetic testament concerning connection, steadfastness, and how to sustain love amidst dispersal.

Poem translator

Kiang Kanghu

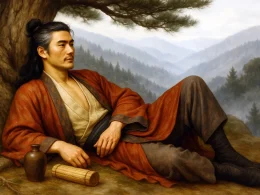

About the poet

Du Fu (杜甫), 712 - 770 AD, was a great poet of the Tang Dynasty, known as the "Sage of Poetry". Born into a declining bureaucratic family, Du Fu had a rough life, and his turbulent and dislocated life made him keenly aware of the plight of the masses. Therefore, his poems were always closely related to the current affairs, reflecting the social life of that era in a more comprehensive way, with profound thoughts and a broad realm. In his poetic art, he was able to combine many styles, forming a unique style of "profound and thick", and becoming a great realist poet in the history of China.