O, sudden wind!

That dimples the spring’s glassy face!

I tease the lovebirds down the flowered trace,

While in my palm red apricot buds I grind.

Lonely by the duck-fight rail,

My jade hairpin slips—half undone.

All day I pine—you come not still—

Till magpies’ glad cries promise the sun!

Original Poem

「谒金门 · 风乍起」

冯延巳

风乍起,吹皱一池春水。

闲引鸳鸯香径里,手桵红杏蕊。

斗鸭阑干独倚,碧玉损头斜坠。

终日望君君不至,举头闻鹊喜。

Interpretation

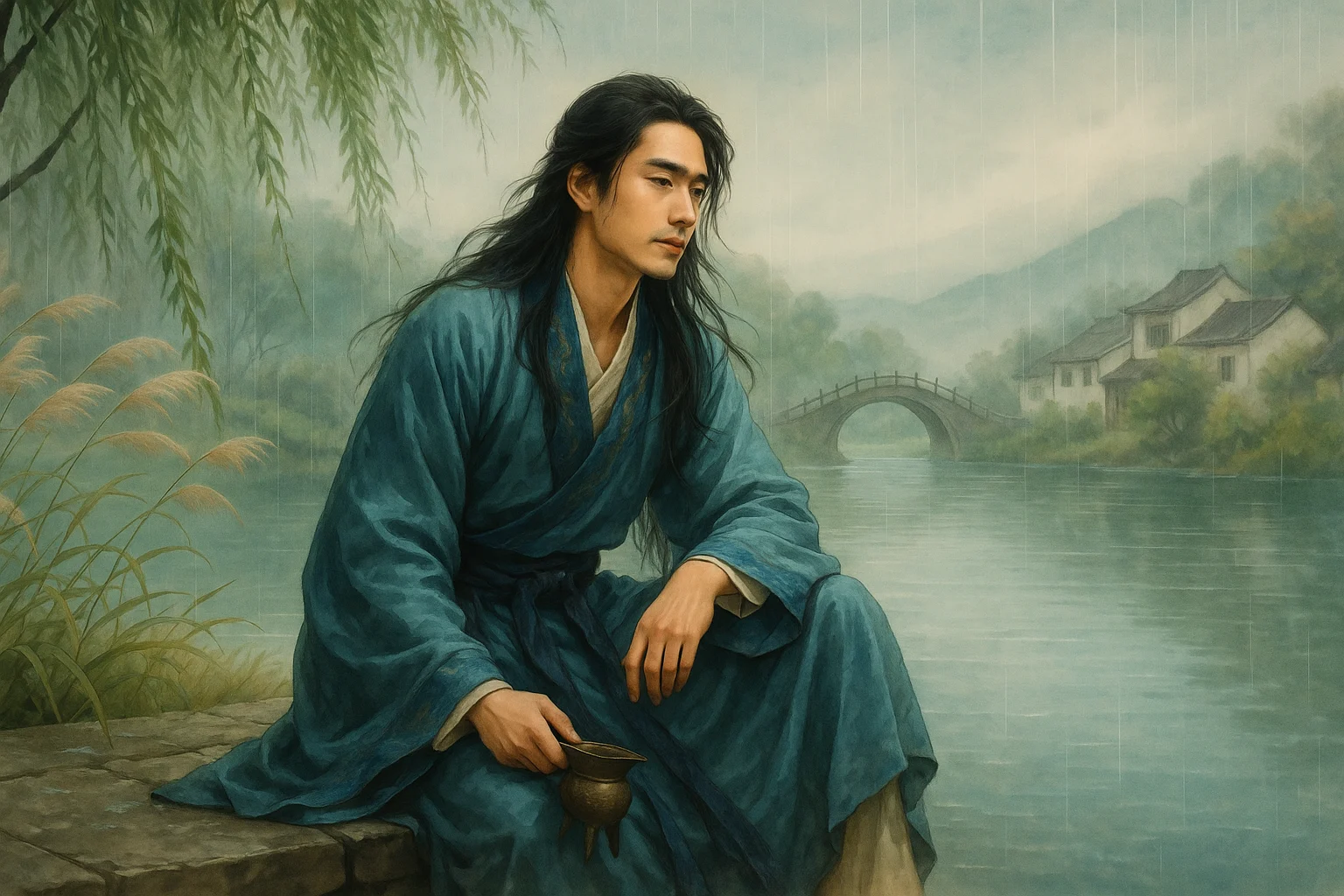

This ci poem, generally attributed to Feng Yansi (with a minority view suggesting Li Yu's authorship), was composed during the Southern Tang period. It portrays an aristocratic woman's delicate psychological state in late spring as she pines for her beloved, capturing the complex emotions of secluded boudoir life—melancholy, longing, and faint hope intertwined.

First Stanza: "风乍起,吹皱一池春水。闲引鸳鸯香径里,手桵红杏蕊。"

Fēng zhà qǐ, chuī zhòu yī chí chūn shuǐ. Xián yǐn yuān yāng xiāng jìng lǐ, shǒu ruí hóng xìng ruǐ.

A sudden breeze ruffles the spring pond's surface,

stirring delicate ripples.

Idly, I lure paired mandarin ducks along the scented path,

plucking and kneading apricot blossoms between my fingers.

The opening lines use the spring breeze as a metaphor for the woman's stirred emotions. The verb "ruffles" (皱) vividly externalizes her inner restlessness. Amidst spring's beauty, her distracted actions—luring ducks (symbols of conjugal bliss) and absentmindedly crushing apricot blossoms—reveal profound loneliness and unspoken envy. The juxtaposition of the paired ducks against her solitary state underscores her emotional isolation.

Second Stanza: "斗鸭阑干独倚,碧玉损头斜坠。终日望君君不至,举头闻鹊喜。"

Dòu yā lán gān dú yǐ, bì yù sǔn tóu xié zhuì. Zhōng rì wàng jūn jūn bù zhì, jǔ tóu wén què xǐ.

Alone, I lean on the railing watching duck fights,

my jade hairpin slipping askew.

All day I wait—yet you never come.

Then, lifting my head, I hear a magpie's call…

The stanza deepens the psychological portrait. "Leaning alone" (独倚) and "all day waiting" (终日望君) emphasize her prolonged, futile vigil. The disheveled hairpin (a detail symbolic of neglected self-care) silently testifies to her obsessive longing. The magpie's call—a traditional omen of good news—offers a glimmer of hope, yet its ambiguity leaves her (and the reader) suspended between anticipation and doubt. The poem ends on this unresolved note, masterfully balancing fragility and fleeting optimism.

Holistic Appreciation

Though compact in form, this ci achieves remarkable depth in both scenery and sentiment, exemplifying Feng Yansi's delicate and nuanced artistic style. Through meticulous depictions of a woman's solitary moments in her courtyard, it transforms inner turmoil into subtle physical gestures. Vivid details like "ruffling spring water," "plucking red apricots," and "jade hairpin tilting askew" progressively intensify her emotional state from quiet melancholy to profound wistfulness. The concluding "hearing magpies' joyful cries" deliberately leaves ambiguous whether her beloved will come, preserving a sliver of hope that poignantly reveals her struggle to find solace in sorrow.

Artistic Merits

The ci's brilliance lies in its microscopic portrayal of inner psychological movements. Minute actions and static scenes convey monumental emotions—particularly "ruffling a pool of spring water" and "jade hairpin tilting askew," which function simultaneously as vivid imagery and psychological symbolism. Structurally, the first stanza depicts spring breezes stirring emotions, while the second shows emotions curdling into sorrow before turning toward hope, creating seamless progression. The refined yet unadorned diction and sincere yet restrained emotions perfectly embody Feng Yansi's signature style of exquisite melancholy.

Insights

This ci uses a noblewoman's idle boudoir scenes to reflect the emotional repression and spiritual confinement imposed by feudal ethics. Even privileged lives of silk and satin couldn't shield women from loneliness and lovesickness. Modern readers can appreciate not only the aesthetic beauty of the lyrical school but also gain empathy for historical women's emotional plights. Like a hauntingly delicate melody, this ci may lack grandiosity but resonates with profound emotional truth that lingers long after reading.

About the Poet

Feng Yansi (冯延巳 903 - 960), courtesy name Zhengzhong, was a native of Guangling (modern-day Yangzhou, Jiangsu) and a renowned ci poet of the Southern Tang during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. Rising to the position of Left Vice Director of the Department of State Affairs (Zuo Puye Tongping Zhangshi), he enjoyed the deep trust of Emperor Li Jing. His ci poetry forged a new path beyond the Huajian tradition, directly influencing later masters like Yan Shu and Ouyang Xiu, playing a pivotal role in the transition of ci from "entertainment for musicians" to "literary expression of scholar-officials."