Long rains just cease—air fresh and wide,

Alone I trace the Yu Creek's side.

My staff probes the wild spring’s bed,

My belt girds young bamboos’ head.

What need for deep contemplation?

Solitude is my aspiration.

Blessed respite from worldly fuss—

My chant cools the sultry dusk.

Original Poem

「夏初雨后寻愚溪」

柳宗元

悠悠雨初霁,独绕清溪曲。

引杖试荒泉,解带围新竹。

沉吟亦何事,寂寞固所欲。

幸此息营营,啸歌静炎燠。

Interpretation

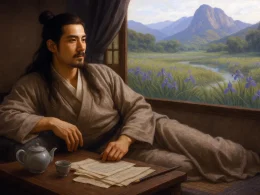

This poem was composed during Liu Zongyuan's exile in Yongzhou, likely after the fifth year of the Yuanhe era (810 AD). By this time, he had settled by Fool's Creek, constructed the "Eight Fools" scenic spots, and was living a life of farming, reading, and self-sufficiency. "Fool's Creek" was Liu Zongyuan's renaming of Ranxi; naming it with "Fool" was both a rejection of worldly cunning and a self-deprecating response to his political failure. Here, he was no longer the determined reformist court official, but a "fool"—content with obscurity, embracing simplicity. This work was written on such a day, after rain in early summer, as the poet visited Fool's Creek alone, seeking spiritual solace in the mountains and waters.

It is worth noting that the emotional tone of this poem differs from the repressed indignation found in Liu Zongyuan's other exile poems. The mood here is more serene and open-minded, showing a spiritual shift towards calm and self-reconciliation in the face of adversity. This is not an escape from reality, but an active spiritual choice—since fate cannot be changed, he changes the way he coexists with it. The entire poem uses simple, plain language to express a transcendent heart, vividly illustrating Liu Zongyuan's change in mindset during his "Fool's Creek period."

First Couplet: "悠悠雨初霁,独绕清溪曲。"

Yōu yōu yǔ chū jì, dú rào qīng xī qū.

Long, long the rain; just cleared, I pace alone

The winding course of the creek's pure flow.

The opening creates a distant, tranquil atmosphere. The word "Long, long" ("悠悠") describes the rain's extended duration, the leisurely pace of time, and, even more, the serenity of the poet's mood. After the rain clears, the air is fresh, everything washed clean—a perfect time for an outing. "I pace alone / The winding course"—the word "alone" ("独") indicates the poet is by himself, yet there is no sense of loneliness, but rather a leisurely contentment. The phrase "winding course of the creek's pure flow" ("清溪曲") describes the lively, meandering creek and subtly hints at the poet's own tortuous fate—the creek's winding path mirrors the trajectory of his life. But at this moment, he is simply "pacing," strolling, quietly facing this creek.

Second Couplet: "引杖试荒泉,解带围新竹。"

Yǐn zhàng shì huāng quán, jiě dài wéi xīn zhú.

I tap a cane to test a wild spring's depth;

Loosen my belt to prop a new bamboo.

This couplet describes the poet's specific actions, where deep meaning resides in minute details. "I tap a cane to test a wild spring's depth"—the wild spring, uncared for by anyone, yet he uses his cane to probe its depth, its temperature. This seemingly idle action symbolizes his exploration of his own inner world: in this remote place of exile, in a situation where none understand, he is still seeking the source of life, still searching for spiritual living water.

"Loosen my belt to prop a new bamboo"—a newly sprouted bamboo, blown over by wind and rain; he loosens his belt, gently props it up, encircles it. This detail is particularly moving. The "new bamboo" could literally refer to the plant, but can also be seen as the poet's care for new life, for younger generations. Though he himself suffered setback, he still maintains a nurturing heart towards life. This "test" and "prop" express the poet's deep affection for nature, for life, letting the reader see that beneath the "fool's" exterior lies a heart still warm.

Third Couplet: "沉吟亦何事,寂寞固所欲。"

Chén yín yì hé shì, jì mò gù suǒ yù.

What is there to brood on, after all?

Solitude is what I've always sought.

This couplet shifts from narration to lyricism, becoming the poet's inner monologue. "Brood" ("沉吟") refers to contemplation, worry—those lingering sorrows of the past, those questions about fate, that confusion about the future. And now, the poet tells himself: what's the use of brooding? What's the point of dwelling on those things? The phrase "after all" ("亦何事") shows him letting go of past entanglements, transcending pointless worries.

"Solitude is what I've always sought" is especially profound. "Solitude" ("寂寞") is seen as painful by ordinary people, yet under the poet's pen, it is "what I've always sought." This is not masochism, but an active choice and affirmation: he has chosen this solitary life; he affirms this is what he truly wants. The word "always" ("固") is strong and firm—it is not forced acceptance, but the original state of his heart. Here, the poet completes a spiritual transformation: from a passive sufferer to an active chooser.

Fourth Couplet: "幸此息营营,啸歌静炎燠。"

Xìng cǐ xī yíng yíng, xiào gē jìng yán yù.

Luckily, here I've ceased my restless toil;

I sing aloud, and the hot day grows still.

The final couplet concludes the poem, pushing the emotion to the peak of open-mindedness. "Restless toil" ("营营") refers to the state of rushing about for fame and profit, toiling for livelihood, alluding to the Zhuangzi: "Preserve your form, embrace your life, and do not let your thoughts be restless and toiling." The poet says, "Luckily, here I've ceased my restless toil"—the word "luckily" ("幸") expresses his relief and gratitude: how fortunate to be able to escape that clamorous world, to settle his body and mind by Fool's Creek!

"I sing aloud, and the hot day grows still" finds coolness in the heat, preserves peace amidst disturbance. "Sing aloud" ("啸歌") is a long, loud chant, a response to nature, an expression of an unburdened heart; the word "grows still" ("静") is key. It is not external stillness, but inner stillness—even amidst the "hot day" ("炎燠"), one can still maintain a coolness and peace. These seven words fully express the poet's resilience and optimism in facing his environment and fate: the external heat cannot be changed, but inner peace can be grasped by oneself.

Holistic Appreciation

This ancient-style pentasyllabic poem uses "seeking the creek after rain" as its thread, completing a purification and sublimation of the soul through the progression of the journey. The first couplet describes walking alone after rain, the atmosphere distant; the second couplet describes testing the spring and propping the bamboo, the details vivid; the third couplet is the inner monologue, a profound turning point; the final couplet describes singing aloud and being at ease, open-minded and transcendent. From external to internal, from scene to feeling, it progresses layer by layer, each part connecting to the next.

The poem's language is simple and plain, its artistic conception serene, yet it contains profound insights into life. The poet does not directly criticize reality, does not vent resentment; he simply, calmly, writes about how he settles his body and mind amidst mountains and waters. Yet it is precisely this calm that reveals a deeper strength—it is not compromise with reality, but transcendence of it; it is not passive escape, but active choice.

Compared to Liu Zongyuan's somber, forceful exile poems, this piece possesses an added serenity and open-mindedness. It bears witness to the poet's journey from initial indignation upon exile, to mid-period discontent, to the gradual calm of this moment—this long spiritual journey condensed into these twenty characters.

Artistic Merits

- Scene and Feeling Fused, Object and Self as One: Specific actions like testing the spring and propping the bamboo are both realistic description and symbolism; the poet's spiritual pursuit merges with the natural scenery.

- Simple, Plain Language, Profound Meaning: The poem contains no obscure or difficult phrases, yet holds deep insights into life. Lines like "What is there to brood on, after all? / Solitude is what I've always sought" reveal profound meaning within plainness.

- Natural Transitions, Clear Progression: From scene to feeling, external to internal, action to monologue, it progresses layer by layer; the structure is rigorous, the flow of thought smooth.

- Using Stillness to Counter Movement, Gentleness to Overcome Harshness: Facing the reality of the "hot day," the poet chooses to respond by "singing aloud," to abide by "stillness," demonstrating an inner strength and resilience.

Insights

This poem first enlightens us on how to achieve spiritual transformation amidst hardship. Liu Zongyuan traveled a long psychological journey from initial indignation upon exile to the present calm. He did not remain in complaint and lament but actively sought a spiritual way out—settling his body and mind in the landscape, affirming himself in solitude. This transformation from passive acceptance to active choice is something everyone facing hardship may experience. It tells us: we cannot choose our fate, but we can choose our attitude towards it; we cannot change our environment, but we can change our own state of mind.

Furthermore, the detail of "I tap a cane to test a wild spring's depth; / Loosen my belt to prop a new bamboo" makes us consider the meaning of action. In hardship, the poet did not wallow in contemplation but interacted with the world through concrete actions—testing the wild spring, propping up the new bamboo. These seemingly small actions were his way of rebuilding life, rebuilding meaning. It enlightens us: In times of confusion, concrete action is more powerful than abstract contemplation. Even doing one small thing can help us regain a sense of control over life.

Looking deeper, the line "Solitude is what I've always sought" is especially worthy of contemplation. In ordinary eyes, solitude is pain, something to avoid. But Liu Zongyuan says: this is precisely what I have "always sought." This is not masochism, but a profound recognition of the value of solitude—only in solitude can one truly face oneself; only in solitude can one hear the voice deep within. It enlightens us: do not fear solitude; solitude holds our deepest encounters with ourselves.

Finally, the word "luckily" in "Luckily, here I've ceased my restless toil" is also thought-provoking. Liu Zongyuan was not forced to "cease restless toil"; he felt "luckily" about it—he was grateful. This posture of gratitude towards fate is not resignation, but transcendence. It tells us: even in the most unbearable circumstances, one can find something to be grateful for; even in a state of deprivation, one can discover new possibilities. This is not an Ah Q-like self-consolation, but a clear-eyed, active choice—to choose to see the light, to cherish the present, to still "sing aloud" amidst the "hot day."

About the Poet

Liu Zongyuan (柳宗元, 773 - 819), a native of Yuncheng in Shanxi province, was a pioneering advocate of the Classical Prose Movement during China's Tang Dynasty. Awarded the prestigious jinshi degree in 793 during the Zhenyuan era, this distinguished scholar-official revolutionized Chinese literature with his groundbreaking essays. His prose works, remarkable for their incisive vigor and crystalline purity, established the canonical model for landscape travel writing that would influence generations. As a poet, Liu mastered a distinctive style of luminous clarity and solitary grandeur, securing his place among the legendary "Eight Great Masters of Tang-Song Prose" - an honor reflecting his enduring impact on Chinese literary history.