Gone is the guest from the Chamber of Rank,

And petals, confused in my little garden,

Zigzagging down my crooked path,

Escort like dancers the setting sun.

Oh, how can I bear to sweep them away?

To a sad-eyed watcher they never return.

Heart's fragrance is spent with the ending of spring

And nothing left but a tear-stained robe.

Original Poem

「落花」

李商隐

高阁客竟去,小园花乱飞。

参差连曲陌,迢递送斜晖。

肠断未忍扫,眼穿仍欲归。

芳心向春尽,所得是沾衣。

Interpretation

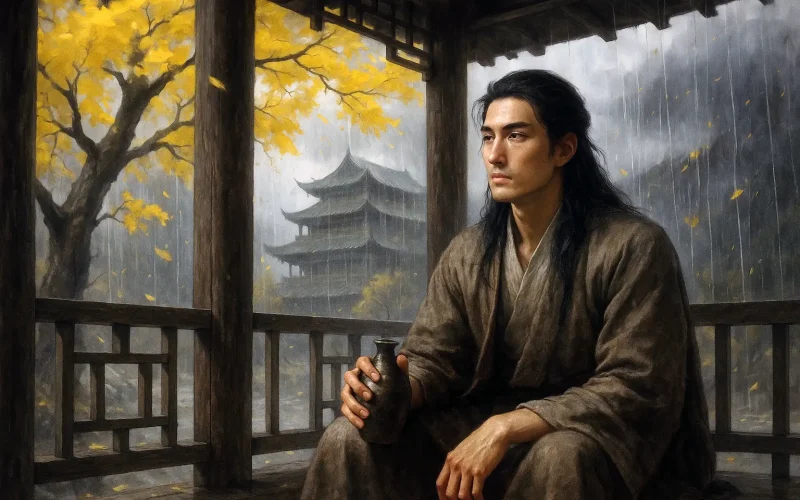

This poem was composed in the late spring of 846 AD, during Li Shangyin's period of forced retirement in Yongle (modern Ruicheng, Shanxi), a direct consequence of his entrapment in the Niu-Li factional strife. This stage marked a crucial turning point in the poet's political life—his marriage to the daughter of Wang Maoyuan had been viewed by the Niu faction as a betrayal, leading to persistent marginalization in his official career. His retirement in Yongle was not a voluntary retreat but the physical manifestation of his political marginalization.

It is worth noting that this period coincided with the final years of Emperor Wuzong's reign and the last phase of Li Deyu's administration, the leader of the Li faction. Residing in Yongle, far from Chang'an, the poet was like the blossoms detached from their branches, cast out from the political center's currents. The scene of "guests have all gone from the high tower" in the poem can be read literally as the dispersal of friends, or metaphorically as the sudden evaporation of political patronage. By this time, Li Shangyin had deeply internalized the natural law that "blooms and falls have their appointed time," yet he maintained, in the line "though my eyes wear out, I long for your return," an untimely persistence. This very contradiction is the key to understanding the poem's emotional depth.

First Couplet: 高阁客竟去,小园花乱飞。

Gāo gé kè jìng qù, xiǎo yuán huā luàn fēi.

From the high tower, the guests have all gone, in the end;

In the small garden, blossoms drift disordered, without friend.

Explication: The word "in the end" (jing) is the couplet's linchpin, carrying both the temporal finality of "finally" and the melancholy surprise of "unexpectedly." The departure of "guests" and the drifting of "blossoms" create a dual sense of loss. More intriguing is the spatial contrast between "high tower" and "small garden": the former symbolizes worldly splendor, the latter a metaphor for the poet's inner realm. As the crowd disperses from the lofty space, the poet withdraws into the lowly garden, only to find nature's feast concluding in parallel. This simultaneous spatial descent and temporal decay intensifies the feeling of existential isolation.

Second Couplet: 参差连曲陌,迢递送斜晖。

Cēnci lián qū mò, tiáodì sòng xié huī.

Uneven, they link the winding garden ways;

Far-reaching, they escort the sun's departing rays.

Explication: This couplet transforms a scene of scattering into a three-dimensional narrative of time and space. "Uneven" describes not just the irregular forms of the fallen blossoms but also echoes the classical rhythm of phrases like "uneven is the water grass" from the Book of Songs, bestowing upon decay a certain aesthetic order in irregularity. "Far-reaching" is doubly meaningful: it depicts the garden paths winding into the distance and hints at the prolonged process of the sunset's fading. The fallen blossoms become a medium connecting earth (winding ways) and sky (departing rays), accomplishing in their fall one last tender contact with the world—not merely a descent, but an "escorting," granting poetic agency to a passive act.

Third Couplet: 肠断未忍扫,眼穿仍欲归。

Cháng duàn wèi rěn sǎo, yǎn chuān réng yù guī.

Heartbroken, I cannot bear to sweep them clear;

Though my eyes wear out, I long for your return.

Explication: This couplet reveals a fierce tug-of-war between reason and emotion, between sight and heart. "Heartbroken" is physiological pain; "cannot bear" is psychological resistance. "Eyes wear out" is sensory extremity; "long for return" is stubborn willpower. Here, the poet undergoes a significant shift in identity: from an observer of the fallen blossoms to their guardian, from a witness of spring's end to its would-be preserver. Sweeping the blossoms is the rational choice (to maintain tidiness); not sweeping them is the emotional choice (to respect the dignity of fading). This choice reveals a profound ethic: the beauty of some things resides precisely in the uninterrupted process of their passing.

Fourth Couplet: 芳心向春尽,所得是沾衣。

Fāng xīn xiàng chūn jìn, suǒ dé shì zhān yī.

Their fragrant heart goes with the ending spring;

All that is gained is this: tear-dampened clothing.

Explication: "Fragrant heart" (fang xin) is the poem's spiritual concentrate, referring both to the soul of the blossoms and the poet's own noble aspiration. "Goes with the ending spring" embodies a tragic beauty of actively moving toward conclusion—not passive withering, but proceeding toward spring despite knowing the end. "Tear-dampened clothing," the poem's sole tactile image, transmutes abstract emotion (sorrow) into concrete physical experience (damp coldness), completing the descent of pain from the spirit to the flesh. In the moment tears dampen his robe, poet and blossom finally merge: both have offered their finest essence as a sacrifice to the spring that must depart.

Holistic Appreciation

The poem's brilliance lies in constructing a complete cosmic model of gathering to scattering, plenitude to decline. Within this model, the guests' departure from the high tower symbolizes the dispersal of the human world, while the blossoms' flight in the small garden symbolizes the decay of the natural world—both pointing to a fundamental law of vanishing.

The poem's structure traces a spiraling descent of mood: the first couplet presents the scene with abrupt clarity (shock); the second extends it spatially (observation); the third reconfigures the subject-object relationship (compassion); the fourth dissolves the boundary between subject and object (sorrow). Through this process, the poet completes a transformation from "observer of blossoms" to "one among the blossoms," ultimately sharing the fate of "going with the ending spring."

Particularly profound is that Li Shangyin does not portray the fallen blossoms merely as passive, scattering objects. "Drift disordered" suggests a spontaneity; "cannot bear to sweep" implies a dignity; "fragrant heart" conveys an active pursuit. This elevates the poem beyond simple lament for spring or self-pity, making it an exploration of how life maintains its spiritual posture within inevitable decay.

Artistic Merits

- The Ordered Collapse of Spatial Hierarchy: The shift in setting—from the high tower (artificial grandeur) to the small garden (natural enclosure) to the winding paths (marginal byways)—subtly charts the poet's progressing marginalization.

- The Dual Dimensions of Temporal Perception: "Departing rays" mark physical time; "ending spring" marks a seasonal cycle's terminus. Meanwhile, "cannot bear" and "long for return" showcase psychological time's resistance to and dilation of physical time.

- The Ultimate Convergence in a Tactile Image: The poem begins with visual imagery (drifting blossoms, sunset rays) and concludes with a tactile sensation (damp clothing). This transforms ineffable grief into a palpable somatic experience, achieving the material conveyance of emotion.

Insights

This work reveals a timeless paradox of existence: our deepest emotional investments are often directed toward that which is fated to vanish. Fully aware that blossoms must fall and spring must end, the poet nonetheless pours forth his "fragrant heart." This posture of "moving toward the end" precisely captures the nobility of the human spirit—for true value lies not in possessing enduring permanence, but in the wholehearted pursuit undertaken in full awareness of transience.

The persistence of "cannot bear to sweep" and the hopeful longing in "long for your return" offer wisdom for facing loss: True cherishing is not about clutching tightly, but about respecting the rhythm of fading and maintaining a gaze of deep affection throughout the process. Sweeping the blossoms away would restore the garden's tidiness but simultaneously negate both the natural process and human feeling. By choosing to let the blossoms remain, Li Shangyin chooses to preserve the complete narrative of "going with the ending spring."

In an era that prizes efficiency and advocates "timely clearing," this poem reminds us: Some "disorder" in life is worth preserving; some "useless" gazing holds profound meaning. The uneven beauty of blossoms covering winding paths, the immersive sorrow of tears dampening clothing—these moments, immeasurable by utilitarian value, are perhaps the precious experiences that distinguish us from tools and confirm our humanity. Ultimately, the poem teaches us not how to avoid the sorrow of "dampened clothing," but how, within such sorrow, to still preserve the integrity and dignity of the "fragrant heart."

Poem translator

Kiang Kanghu

About the poet

Li Shangyin (李商隐), 813 - 858 AD, was a great poet of the late Tang Dynasty. His poems were on a par with those of Du Mu, and he was known as "Little Li Du". Li Shangyin was a native of Qinyang, Jiaozuo City, Henan Province. When he was a teenager, he lost his father at the age of nine, and was called "Zheshui East and West, half a century of wandering".