A southern post differs from northern sphere,

To westward turn—eastward I dare not steer.

Through moonlit clouds the mournful monkeys call,

Wind sweeps the dew-damp枕 on river's thrall.

Spring turns the locks that once were raven-black,

Wine cannot warm these pallid cheeks alack.

Grieve not for ailments nor for cares that rend—

They shall be this old man's faithful friend.

Original Poem

「解舟惠州东桥」

杨万里

南宦宁差北,西归敢再东。

猿声云树月,客枕露船风。

绿发春全白,苍颜酒不红。

莫憎愁与病,留取伴衰翁。

Interpretation

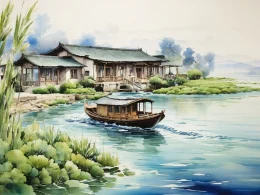

Written during Yang Wanli's exile in Huizhou. In the Southern Song Dynasty, Yang's official career was fraught with setbacks, and in his later years, he was relegated to Lingnan due to political disagreements. Huizhou was a remote place with a tranquil environment, and the poet often drew inspiration from scenes during his boat journeys, composing poems accordingly. This work was penned during a moment of reflection while moored at East Bridge in Huizhou. It describes the sights and sounds of his journey while also conveying life's contemplations, revealing the solitude and resilience of the poet in his later years.**

First Couplet: "南宦宁差北,西归敢再东。"

Nán huàn nìng chà běi, xī guī gǎn zài dōng.

A southern appointment differs little from a northern one;

Daring to head west, would I venture east again?

The opening lines highlight "southern appointment" (南宦 nán huàn),暗示 (hinting at) the helplessness of an exile's life; "daring to head west… east again" conveys the frustration of an unfulfilled career, repeated漂泊 (wandering), and elusive homecoming.

Second Couplet: "猿声云树月,客枕露船风。"

Yuán shēng yún shù yuè, kè zhěn lù chuán fēng.

Gibbon cries among cloud-veiled trees and moon;

The traveler’s pillow knows dew and boat-borne wind.

This couplet depicts the night at anchor. Gibbon calls sound piercing, moonlight filters faintly, wind and dew intrude—together crafting an aura of solitary journey’s chill, mirroring the poet’s inner loneliness.

Third Couplet: "绿发春全白,苍颜酒不红。"

Lǜ fà chūn quán bái, cāng yán jiǔ bù hóng.

Once-green hair now wholly white with spring’s passing;

A weathered face wine cannot flush.

Here, personal emotion is laid bare. "Once-green hair wholly white" speaks to time’s swift passage; "wine cannot flush" admits aging’s reality—both lines流露出 (revealing) lament for life’s fleetingness.

Fourth Couplet: "莫憎愁与病,留取伴衰翁。"

Mò zēng chóu yǔ bìng, liú qǔ bàn shuāi wēng.

Do not resent sorrow and sickness;

Let them stay as companions to this declining elder.

The conclusion turns to self-consolation, shifting from sighing over age to calm acceptance. Blending resignation and豁达 (resignation), it reflects the poet’s wisdom in seeking balance amid life’s trials.

Holistic Appreciation

This is a classic work of exile reflection. Using the night mooring as a starting point, the poet writes of career wandering and aging, with genuine and profound emotion. The first two couplets depict the hardships of travel and the journey’s scenery, blending natural imagery—gibbon cries, clouded trees, moon, wind, and dew—with the solitude of travel; the latter couplets express human concerns, sighing at time’s passage and the reality of decline.

The poem’s artistic charm lies in scene imbued with feeling, emotion revealing truth. Rather than directly complaining, the poet uses the night mooring as backdrop, naturally merging travel weariness with life’s reflections, achieving subtle depth. The ending, "Do not resent sorrow and sickness," carries philosophical weight: since hardship and illness are unavoidable, accept them as life’s constants and coexist with them. This transcendent resilience lends the poem a tone of peace amid sorrow.

Artistic Merits

- Fusion of feeling and scene: Gibbon cries, moon, wind, and dew are not just natural descriptions but reflections of the poet’s inner solitude, blending scene and emotion seamlessly.

- Simple, natural language: The poem uses plain diction, straightforward yet sincere—e.g., "once-green hair wholly white, weathered face wine cannot flush" is unadorned but deeply moving.

- Small revealing large, subtle yet profound: A single night’s mooring expands into themes of life’s wandering and aging, progressing from minor to major, layer by layer.

- Well-turned transition, rich in philosophy: The first three couplets express the pains of exile and aging; the final couplet turns to self-consolation, creating an emotional "shift" infused with enlightened wisdom.

Insights

This poem teaches that life inevitably involves wandering and aging—instead of resenting them, one must learn to find peace amid adversity. As the poet says, sorrow and sickness are also life’s companions. Accepting them is the path to tranquility. The wisdom in Yang Wanli’s later works remains relevant: in life’s unpredictability, making peace with oneself is true resilience.

About the Poet

Yang Wanli (杨万里 1127 - 1206), a native of Jishui in Jiangxi, was a renowned poet of the Southern Song Dynasty, celebrated as one of the "Four Great Masters of the Restoration" alongside Lu You, Fan Chengda, and You Mao. He attained the jinshi degree in 1154 and rose to the position of Academician of the Baomo Pavilion. Breaking free from the constraints of the Jiangxi School of Poetry, he pioneered the lively and natural "Chengzhai Style," advocating for learning from nature and employing plain yet profound language. His poetry, often drawing inspiration from everyday life, profoundly influenced later schools of lyrical expression, particularly the Xingling (Spirit and Sensibility) School.