See the clear river wind by the village and flow!

We pass the long summer by riverside with ease.

The swallows freely come in and freely out go.

The gulls on water snuggle each other as they please.

My wife draws lines on paper to make a chessboard;

My son bends a needle into a fishing hook.

Ill, I need only medicine I can afford.

What else do I want for myself in my humble nook?

Original Poem

「江村」

杜甫

清江一曲抱村流,长夏江村事事幽。

自去自来堂上燕,相亲相近水中鸥。

老妻画纸为棋局,稚子敲针作钓钩。

但有故人供禄米,微躯此外更何求?

Interpretation

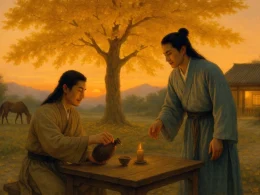

This work was composed in the summer of 760 CE, the first year of the Shangyuan era under Emperor Suzong, soon after Du Fu first settled into his thatched cottage by the Huanhua Stream in Chengdu. The An Lushan Rebellion still raged unabated in the Central Plains, casting the heartland into turmoil. Having survived a fugitive’s life of foraging for sustenance, the poet managed, with financial aid from friends like Yan Wu, to build this cottage and secure temporary refuge. Though his livelihood remained dependent on the support of old acquaintances and was marked by profound poverty, compared to the years of relentless, desperate flight, it felt like a haven of peace. This poem stands as a truthful portrait of a precious interlude of tranquility grasped within the cracks of ongoing war. It reveals a deep-seated, steady joy within the plain routines of domesticity, while its expressions of contentment are tinged with a sorrow that is sensed rather than stated.

First Couplet: “清江一曲抱村流,长夏江村事事幽。”

Qīng jiāng yī qǔ bào cūn liú, cháng xià jiāng cūn shì shì yōu.

A clear stream, winding, flows, the village in its fond embrace; / The long summer in this river-hamlet shows a tranquil, quiet grace.

The opening unfolds like a serene ink-wash scroll. "A clear stream, winding, flows" captures the water’s lucidity and gentle, meandering course. The phrase "the village in its fond embrace" uses the verb "embrace" to endow the river with a tender, almost affectionate quality, establishing the poem’s foundational tone of peaceful intimacy. "The long summer" fixes the season, implicitly suggesting a dilation of time itself. "Shows a tranquil, quiet grace" offers a summative aesthetic judgment. The word "tranquil" describes both the secluded, hushed environment and, more deeply, a state of mind characterized by quiet contentment, setting the stage for the specific descriptions that follow.

Second Couplet: “自去自来堂上燕,相亲相近水中鸥。”

Zì qù zì lái táng shàng yàn, xiāng qīn xiāng jìn shuǐ zhōng ōu.

At will they come and go, the swallows underneath the eaves; / In fond companionship, the river-gulls upon the water’s face.

The poet selects two creatures—one from the domestic sphere beneath the rafters, one from the natural world upon the water—and employs a parallel, complementary structure to sketch a scene of harmonious coexistence where all beings are content in their place. "At will they come and go" depicts the swallows’ utter freedom; "in fond companionship" captures the gulls’ affectionate camaraderie. Swallows nesting in the eaves are companions of the household; gulls upon the water belong to the scenery of the riverside. One pair suggests motion, the other calm; one near, the other far. Together, they evoke a world free from disturbance, where all life follows its natural, untroubled course. This is not merely objective description but the projection of the poet’s own inner yearning for freedom, affinity, and peace onto the world around him.

Third Couplet: “老妻画纸为棋局,稚子敲针作钓钩。”

Lǎo qī huà zhǐ wéi qí jú, zhì zǐ qiāo zhēn zuò diào gōu.

My aging wife designs a chessboard on a sheet of paper spread; / My little boy bends out a needle for a fishing line’s tip instead.

The focus turns inward, to the family circle, capturing two moments rich in the charm of simple, resourceful living. "Designs a chessboard on a sheet of paper" reveals a household too poor for a proper board, yet one that finds intellectual delight in improvisation. "Bends out a needle for a fishing line’s tip" shows a child’s ingenuity, turning a mundane object into a tool for play and, implicitly, for supplementing the family’s meager diet. With the plainest of brushstrokes, the poet depicts the highest form of happiness available to an impoverished family in a time of chaos: the safety of loved ones, the warmth of their company, and the capacity to create simple pleasures within hardship. The aging wife’s quiet focus and the young son’s lively activity complement each other, a portrait of moving domestic tenderness.

Fourth Couplet: “但有故人供禄米,微躯此外更何求?”

Dàn yǒu gùrén gōng lù mǐ, wēi qū cǐ wài gèng hé qiú?

If only my old friends supply the rice that lets this life endure, / What more, then, could this humble self of mine from fate yet hope to secure?

After the first three couplets have constructed a scene of serenity and familial warmth so complete it feels idyllic, this final couplet quietly but starkly reveals the fragile material foundation upon which that peace rests: the "rice" supplied by "old friends." These five plain words contain the helplessness of a scholar stripped of economic autonomy by war and the unspoken ache of dependence. Yet, the poet frames this reality with the rhetorical structure "If only… what more"—a formulation that transforms acknowledged vulnerability into a statement of resolute, almost defiant, contentment and gratitude. This "contentment" is weighty, rooted in reliance; this "gratitude" is profound, born of an absolute cherishing of the concrete warmth that reliance makes possible. The final line is both a sigh of relief and a sigh of resignation—a negotiated, minimal peace with circumstance.

Holistic Appreciation

This work is a cornerstone of Du Fu’s pastoral poetry. Its greatness lies in its unflinching and profound portrayal of the complex nature of "happiness grasped in the interstices of suffering." The poem’s structure is masterful, advancing in clear, logical stages: from the serenity of the setting (the river-hamlet) → to the harmony of nature (swallows and gulls) → to the joy of the household (wife and son) → to the foundation of survival (the friend’s rice), culminating in a sigh that mingles deep satisfaction with profound melancholy.

The poem’s surface radiates a quiet, pervasive joy, yet just beneath flows a powerful undercurrent of precariousness. The "at will" swallows and the "fond" gulls highlight, by contrast, the displacement and alienation of human society. The refined pleasure of a "chessboard on paper" conceals the stark reality of a threadbare home. The sustenance of "rice supplied by old friends" underscores a hand-to-mouth existence. This is the poetic equivalent of a "smile through tears"—the noble stance of a poet who, having fully apprehended life’s bitterness, still chooses to love and celebrate every fragment of its warmth.

Artistic Merits

- Exquisite, Seemingly Effortless Parallelism: The parallel structure of the two central couplets is crafted with superb skill. "At will they come and go" mirrors "in fond companionship"; the use of reduplication enhances the melodic, rhythmic quality. "Underneath the eaves" pairs with "upon the water’s face," creating a pleasing spatial composition. "My aging wife" is balanced against "my little boy"; "designs a chessboard" against "bends out a needle"; "chessboard" against "fishing line’s tip." The domestic vignettes are vividly pictorial, their formal balance brimming with quiet vitality.

- The Epistolary Power of Precise Detail: Details like "designs a chessboard on a sheet of paper" and "bends out a needle for a fishing line’s tip" possess a timeless, universal power precisely because of their extreme specificity and ordinariness. They transcend being mere snapshots of Du Fu’s family life to become enduring symbols for all families striving to preserve human dignity, affection, and simple pleasures amidst the poverty and dislocation of war.

- Profound Emotional Tension in the Juxtaposition of Joy and Sorrow: The poem describes serene vistas, harmonious creatures, and domestic tenderness almost exclusively. Only in the final couplet is the precarious economic basis of this peace lightly touched upon. This technique—"using scenes of joy to convey a substratum of sorrow"—intensifies the feeling: the deeper the portrayed contentment, the heavier the underlying sense of fragility and melancholy, creating a potent and resonant emotional tension.

- A Language of Supreme Purity and Concentration: The poem employs no arcane diction or obscure allusions; its language is transparent, almost conversational. Yet within its forty characters, it successfully fuses landscape, family life, personal reflection, and the imprint of a historical epoch. It achieves that highest artistic realm where all ornamentation falls away to reveal a core of pure, unadorned truth.

Insights

This masterpiece offers enduring insight into "how to anchor the value and experience of happiness within a context of profound uncertainty." Du Fu found himself in a position of absolute vulnerability—his nation shattered, his home lost, his livelihood dependent on the goodwill of others. Yet he did not succumb to despair. He trained his gaze on the "winding stream," the "swallows underneath the eaves," the "gulls upon the water." He poured his affection into the mundane moments of his "wife design[ing] a chessboard" and his "son bend[ing] out a needle." Upon the most minimal foundation for survival—"rice supplied by old friends"—he constructed a rich, steadfast world of inner peace and familial joy.

The poem reminds us that happiness may not reside in absolute security or material plenty, but in whether we possess Du Fu’s "tranquil" vision—the ability to discern peace within tumult, to generate delight from scarcity, to feel gratitude within dependence, and to love, perceive, and cherish the concrete people and things immediately before us with our whole being, in the limited and fragile "present moment." The concluding question, "What more… could this humble self… hope to secure?" is simultaneously an acceptance of life’s constraints and a transcendence of them. It is an acknowledgment of limits, and within those very limits, the fearless cultivation of an infinite spiritual landscape.

Poem translator

Xu Yuanchong (许渊冲)

About the poet

Du Fu (杜甫), 712 - 770 AD, was a great poet of the Tang Dynasty, known as the "Sage of Poetry". Born into a declining bureaucratic family, Du Fu had a rough life, and his turbulent and dislocated life made him keenly aware of the plight of the masses. Therefore, his poems were always closely related to the current affairs, reflecting the social life of that era in a more comprehensive way, with profound thoughts and a broad realm. In his poetic art, he was able to combine many styles, forming a unique style of "profound and thick", and becoming a great realist poet in the history of China.