Ten years parted—dead and alive both lost,

Though unrecalled, the memory stays.

Your lonely grave a thousand miles away,

Where could I pour out my heart's cost?

Even if we met now, would you know

This dust-strewn face, this frost-white brow?

Last night in dream I wandered home once more,

Saw you by the casement, combing your hair.

We gazed in silence, speechless there,

Only a thousand streams of tears we bore.

Year after year my heart must break

Where moonlight bathes your pine-clad grave.

Original Poem

「江城子 · 乙卯正月二十日夜记梦」

十年生死两茫茫,不思量,自难忘。

千里孤坟,无处话凄凉。

纵使相逢应不识,尘满面,鬓如霜。夜来幽梦忽还乡,

苏轼

小轩窗,正梳妆。

相顾无言,惟有泪千行。

料得年年肠断处,明月夜,短松冈。

Interpretation

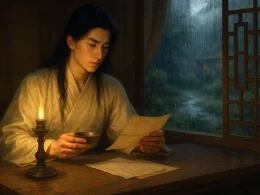

Composed in 1075 during Su Shi's tenure as Mizhou prefect, this cí stands as the pinnacle of Chinese elegiac poetry. Written on the tenth anniversary of his first wife Wang Fu's death, the work transcends personal mourning to explore memory's cruel precision and time's erosive power. Its revolutionary structure—moving between documentary realism and oneiric surrealism—established new emotional parameters for the cí form.

Upper Stanza: "十年生死两茫茫,不思量,自难忘。千里孤坟,无处话凄凉。纵使相逢应不识,尘满面,鬓如霜。"

Shí nián shēngsǐ liǎng mángmáng, bù sīliang, zì nánwàng. Qiānlǐ gū fén, wú chù huà qīliáng. Zòngshǐ xiāngféng yīng bù shí, chén mǎn miàn, bìn rú shuāng.

Ten years—dead and living dim beyond knowing.

I don't brood,

Yet can't forget.

Her lone grave a thousand miles off—

Nowhere to voice this desolation.

Should we meet now, she wouldn't know me—

Dust coats my face,

Hair like frost.

The opening couplet's numerical precision ("ten years," "thousand miles") underscores grief's mathematical cruelty. The paradox "don't brood/Yet can't forget" (不思量,自难忘) reveals memory's autonomic tyranny—the harder one resists remembrance, the more it persists. "Dust" and "frost" materialize time's ravages not as abstractions but as epidermal realities.

Lower Stanza: "夜来幽梦忽还乡,小轩窗,正梳妆。相顾无言,惟有泪千行。料得年年肠断处,明月夜,短松冈。"

Yè lái yōu mèng hū huán xiāng, xiǎo xuān chuāng, zhèng shūzhuāng. Xiānggù wúyán, wéiyǒu lèi qiān háng. Liàodé nián nián cháng duàn chù, míngyuè yè, duǎn sōng gāng.

Last night, a dream suddenly took me home—

By the casement,

She was combing her hair.

We gazed without words,

Only a thousand streams of tears.

I know the place that yearly breaks my heart—

Moonlit nights,

That low-pine mound.

The dream sequence achieves unbearable intimacy through domestic minutiae—the "casement" framing her eternal toilette. Their silent communion ("without words") speaks grief's true language, where tears outnumber syllables. The prophetic "yearly breaks my heart" (年年肠断处) transforms personal mourning into cyclical cosmic ritual, with the "low-pine mound" (短松冈) becoming an astral calendar marking lunar grief-anniversaries.

Holistic Appreciation

This deeply moving elegy expresses Su Shi’s undiminished grief for his late wife, Wang Fu, a decade after her passing. The first stanza employs plain yet piercing realism, laying bare the anguish of eternal separation with unadorned language. The second stanza shifts to a dreamscape, where the poet and his wife reunite in silent communion—their wordless tears speaking volumes beyond speech. Blending reality and illusion, the poem crafts an atmosphere of haunting sorrow and quiet devastation.

The paradoxical lines "not dwelling on memories, yet never forgetting" capture the poet’s tormented ambivalence, while the vivid dream sequence conveys timeless longing. By merging personal loss with universal grief, the poem transcends individual mourning to become an immortal masterpiece of elegiac literature.

Artistic Merits

- Reality-Dream Dialectic

The contrast between the daytime lament (real) and nocturnal vision (dream) intensifies emotional impact, revealing grief’s inescapable grip. - Unembellished Authenticity

Su Shi’s plainspoken diction—devoid of ornate phrasing—mirrors raw sorrow, proving that profundity needs no rhetorical adornment. - Condensed Intensity

Short, rhythmic lines build cumulative emotional force, with each phrase deepening the ache of absence. - Silence as Eloquence

The dream’s mute tears articulate more than words could, embodying grief’s inexpressible depth.

Insights

True emotion requires no lavish ornamentation—authenticity alone moves the soul. Su Shi’s unvarnished language channels universal sorrow, laying bare humanity’s helplessness before mortality while affirming love’s persistence beyond death. The interplay of dream and reality mirrors life’s cruel transience against enduring bonds, teaching us to cherish the present while accepting impermanence.

This poem is more than a personal lament; it is a philosophical meditation on love, loss, and resilience. Its emotional honesty and artistic mastery render it an enduring cultural treasure, reminding us that even the sharpest grief can be transmuted into transcendent art.

About the Poet

Su Shi (苏轼, 1037 - 1101), a native of Meishan in Sichuan, was a polymath of the Northern Song literary world. His prose was expansive and unrestrained, his poetry fresh and vigorous, and his ci poetry pioneered the bold and unconstrained style. In calligraphy, he created the "Su Style," and in painting, he championed "spiritual resonance," earning him a place among the "Four Masters of the Song." Despite repeated political persecutions—most notably the "Poetry Case of the Black Terrace"—his exile to Huangzhou, Huizhou, and Danzhou yielded timeless masterpieces. Lu You praised him as "the literary patriarch of an era."