The Son of Heaven, in Yuanhe times, was martial as a god,

And might be likened only to the Emperors Xuan and Xi.

He took an oath to reassert the glory of the empire,

And tribute was brought to his palace from all four quarters.

Western Huai, for fifty years, had been a bandit country —

Wolves becoming lynxes, lynxes becoming bears.

They assailed the mountains and rivers, rising from the plains,

With their long spears and sharp lances aimed at the sun.

But the Emperor had a wise premier, by the name of Du,

Who, guarded by spirits against assassination,

Hung at his girdle the seal of state, and accepted chief command,

While these savage winds were harrying the flags of the Ruler of Heaven.

Generals Suo, Wu, Gu, and Tong became his paws and claws;

Civil and military experts brought their writing brushes,

And his recording adviser was wise and resolute.

A hundred and forty thousand soldiers, fighting like lions and tigers,

Captured the bandit chieftains for the Imperial Temple.

So complete a victory was a supreme event;

And the Emperor said: “To you, Du, should go the highest honour,

And your secretary, Yu, should write a record of it.”

When Yu had bowed his head, he leapt and danced, saying:

“Historical writings on stone and metal are my especial art;

And, since I know the finest brush-work of the old masters,

My duty in this instance is more than merely official,

And I should be at fault if I modestly declined.”

The Emperor, on hearing this, nodded many times.

And Yu retired and fasted and, in a narrow workroom,

His great brush thick with ink as with drops of rain,

Chose characters like those in the Canons of Yao and Xun,

And a style as in the ancient poems Qingmiao and Shengmin.

And soon the description was ready, on a sheet of paper.

In the morning he laid it, with a bow, on the purple stairs.

He memorialized the throne: “I, unworthy,

Have dared to record this exploit, for a monument.”

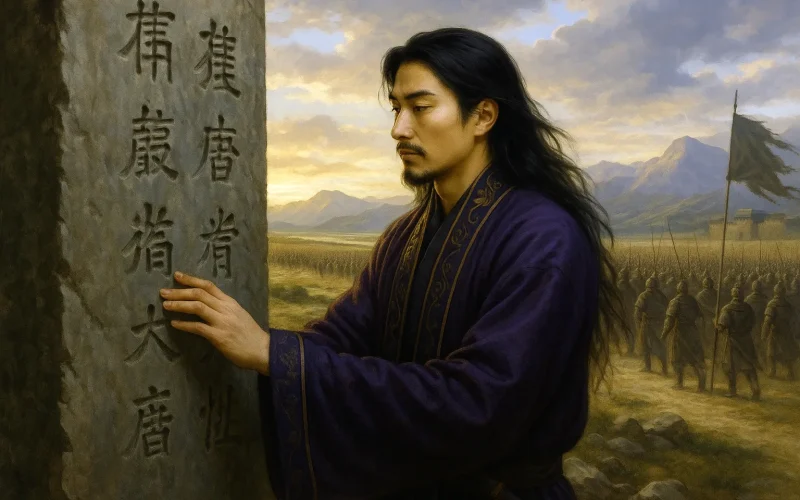

The tablet was thirty feet high, the characters large as dippers;

It was set on a sacred tortoise, its columns flanked with dragons…

The phrases were strange with deep words that few could understand;

And jealousy entered and malice and reached the Emperor —

So that a rope a hundred feet long pulled the tablet down

And coarse sand and small stones ground away its face.

But literature endures, like the universal spirit,

And its breath becomes a part of the vitals of all men.

The Tang plate, the Confucian tripod, are eternal things,

Not because of their forms, but because of their inscriptions…

Sagacious is our sovereign and wise his minister,

And high their successes and prosperous their reign;

But unless it be recorded by a writing such as this,

How may they hope to rival the three and five good rulers?

I wish I could write ten thousand copies to read ten thousand times,

Till spittle ran from my lips and calluses hardened my fingers,

And still could hand them down, through seventy-two generations,

As corner-stones for Rooms of Great Deeds on the Sacred Mountains.

Original Poem

「韩碑」

李商隐

元和天子神武姿, 彼何人哉轩与羲,

誓将上雪列圣耻, 坐法宫中朝四夷。

淮西有贼五十载, 封狼生貙貙生罴;

不据山河据平地, 长戈利矛日可麾。

帝得圣相相曰度, 贼斫不死神扶持。

腰悬相印作都统, 阴风惨澹天王旗。

愬武古通作牙爪, 仪曹外郎载笔随。

行军司马智且勇, 十四万众犹虎貔。

入蔡缚贼献太庙。 功无与让恩不訾。

帝曰汝度功第一, 汝从事愈宜为辞。

愈拜稽首蹈且舞, 金石刻画臣能为。

古者世称大手笔, 此事不系于职司。

当仁自古有不让, 言讫屡颔天子颐。

公退斋戒坐小阁, 濡染大笔何淋漓。

点窜尧典舜典字, 涂改清庙生民诗。

文成破体书在纸, 清晨再拜铺丹墀。

表曰臣愈昧死上, 咏神圣功书之碑。

碑高三丈字如斗, 负以灵鳌蟠以螭。

句奇语重喻者少, 谗之天子言其私。

长绳百尺拽碑倒。 粗沙大石相磨治。

公之斯文若元气, 先时已入人肝脾。

汤盘孔鼎有述作, 今无其器存其辞。

呜呼圣皇及圣相, 相与烜赫流淳熙。

公之斯文不示后, 曷与三五相攀追?

愿书万本诵万过, 口角流沫右手胝;

传之七十有二代, 以为封禅玉检明堂基。

Interpretation

This poem was composed in the early Dazhong era (approximately 847-850 CE) under Emperor Xuanzong of Tang, when Li Shangyin was nearing forty. Having personally endured the Niu-Li factional strife, he felt keenly the maladies of court politics and the plight of the literati. The historical event it recounts occurred in the 13th year of the Yuanhe era (818 CE): after Emperor Xianzong of Tang quelled the Huaixi rebellion, he ordered Han Yu to compose "The Stele of Pacifying Huaixi" to commemorate the achievement. The inscription highlighted the coordinating merit of Chancellor Pei Du, provoking dissatisfaction from the principal commander Li Su (who led the surprise night attack on Caizhou) and his wife (daughter of Princess Tang'an), who petitioned the emperor. This ultimately led to the stele being defaced and Duan Wenchang being commissioned to write a new one. This incident was not merely a dispute over words but an epitome of the civil-military tensions and the struggle between eunuchs and court officials in the mid-to-late Tang. By choosing this subject, Li Shangyin not only expressed his admiration for Han Yu's classical prose spirit but also used the past to criticize the present, venting his complex reflections on the fate of literary works, historical judgment, and political reality. It reflects the shift in his later poetic style towards a more vigorous and profound mode.

Stanza one

元和天子神武姿,彼何人哉轩与羲。

Yuánhé tiānzǐ shén wǔ zī, bǐ hé rén zāi Xuān yǔ Xī.

誓将上雪列圣耻,坐法宫中朝四夷。

Shì jiāng shàng xuě liè shèng chǐ, zuò fǎ gōng zhōng cháo sìyí.

淮西有贼五十载,封狼生貙貙生罴。

Huáixī yǒu zéi wǔshí zài, fēng láng shēng chū chū shēng pí.

不据山河据平地,长戈利矛日可麾。

Bù jù shānhé jù píngdì, cháng gē lì máo rì kě huī.

*The Yuanhe Son of Heaven, divine and martial in bearing— / To whom can he be compared? Only to Xuanyuan and Fuxi! / He vowed to wash away the shame of his royal forebears, / Seated in his palace, receiving tribute from the Four Barbarians. / For fifty years, bandits infested Huaixi, / A fierce wolf breeding *chū*, the *chū* breeding bears. / They held not mountains or rivers but flat plains, / Their long spears and sharp halberds seemed fit to command the sun.*

The opening establishes a majestic tone, comparing Emperor Xianzong of Tang to ancient sage-kings, highlighting his ambition to restore imperial authority. The line, "He vowed to wash away the shame of his royal forebears," reveals that the Huaixi campaign was not merely a military action but a symbolic event for the dynasty to reclaim its dignity. The description of the rebels is particularly artful: "A fierce wolf breeding chū, the chū breeding bears" uses the metaphor of savage beasts multiplying to represent the rebel forces' succession and escalation across generations. "Their long spears and sharp halberds seemed fit to command the sun" alludes to the legend of Lu Yang wielding his spear to halt the sun, hyperbolically portraying their rampant arrogance. Within this grand historical perspective, the suppression of the rebellion is imbued with weighty significance for the nation's fate.

Stanza two

帝得圣相相曰度,贼斫不死神扶持。

Dì dé shèng xiàng xiàng yuē Dù, zéi zhuó bù sǐ shén fúchí.

腰悬相印作都统,阴风惨澹天王旗。

Yāo xuán xiàng yìn zuò dūtǒng, yīn fēng cǎndàn tiānwáng qí.

愬武古通作牙爪,仪曹外郎载笔随。

Sù Wǔ Gǔ Tōng zuò yá zhǎo, yí cáo wàiláng zài bǐ suí.

行军司马智且勇,十四万众犹虎貔。

Xíngjūn sīmǎ zhì qiě yǒng, shísì wàn zhòng yóu hǔ pí.

入蔡缚贼献太庙,功无与让恩不訾。

Rù Cài fù zéi xiàn tàimiào, gōng wú yǔ ràng ēn bù zī.

The emperor gained a sage minister named Du, / Who, slashed by rebels but kept alive, had divine support. / The seal of chancellor hung at his waist, he took command as commander-in-chief, / Under gloomy winds, the Celestial Emperor's banners streamed. / Su, Wu, Gu, and Tong served as his claws and fangs; / Secretaries from the Board of Rites followed, brushes in hand. / The Army Supervisor was wise and brave; / His host of a hundred and forty thousand was like tigers and panthers. / They entered Cai, bound the rebels, offered them at the Ancestral Temple; / Their merit brooked no denial, the imperial favor knew no measure.

This section turns to specific narration, focusing on the central figures and the pivotal battle of the suppression. With concise brushstrokes, the poet outlines a complete military picture: Pei Du, as commander-in-chief, takes personal command, "the seal of chancellor hung at his waist," demonstrating his responsibility; the environmental description "Under gloomy winds" sets a solemn and stirring atmosphere. Referring to generals like Li Su as "claws and fangs" highlights their ferocity but also subtly hints at their subordinate status—a nuance that foreshadows the later controversy. "They entered Cai, bound the rebels" succinctly summarizes the victory, while the judgment "Their merit brooked no denial, the imperial favor knew no measure" introduces the subsequent rewards and the stele inscription.

Stanza three

帝曰汝度功第一,汝从事愈宜为辞。

Dì yuē rǔ Dù gōng dì yī, rǔ cóngshì Yù yí wéi cí.

愈拜稽首蹈且舞,金石刻画臣能为。

Yù bài qǐshǒu dǎo qiě wǔ, jīnshí kèhuà chén néng wéi.

古者世称大手笔,此事不系于职司。

Gǔ zhě shì chēng dàshǒubǐ, cǐ shì bù xì yú zhísī.

当仁自古有不让,言讫屡颔天子颐。

Dāng rén zìgǔ yǒu bù ràng, yán qì lǚ hàn tiānzǐ yí.

公退斋戒坐小阁,濡染大笔何淋漓。

Gōng tuì zhāijiè zuò xiǎo gé, rúrǎn dà bǐ hé línlí.

点窜尧典舜典字,涂改清庙生民诗。

Diǎncuàn Yáodiǎn Shùndiǎn zì, túgǎi Qīngmiào Shēngmín shī.

文成破体书在纸,清晨再拜铺丹墀。

Wén chéng pò tǐ shū zài zhǐ, qīngchén zàibài pù dān chí.

表曰臣愈昧死上,咏神圣功书之碑。

Biǎo yuē chén Yù mèisǐ shàng, yǒng shénshèng gōng shū zhī bēi.

*The emperor said, "Du, your merit is first; / Your subordinate, Yu, should compose the text." / Yu bowed his head, then leapt and danced, / "Inscribing metal and stone—this subject can do it! / Since ancient times, such work is called a masterpiece, / This matter is not bound by official duty. / To what is right, men since old have yielded not." / Having spoken, he saw the Son of Heaven nod his head. / The Duke withdrew, fasted, sat in a small chamber; / How freely flowed his great brush steeped in ink! / He emended phrases from the *Canons of Yao and Shun*, / Altered lines from the *Temple Clear* and Birth of Our People. / The text done, in a unique script he wrote it on paper; / At dawn, again he bowed, spread it on the vermilion steps. / A memorial said: "Your subject Yu, risking death, presents this, / Singing the holy, divine merit, to be engraved upon the stele."*

This section dramatically depicts the process of Han Yu receiving the commission to write the inscription. "Leapt and danced" vividly portrays Han Yu's confidence and passion. His declaration that a "masterpiece" is "not bound by official duty" is, in essence, a justification for a literatus's right to participate in major historical writing. The hyperbolic statements "emended phrases from the Canons of Yao and Shun" and "altered lines from the Temple Clear and Birth of Our People" do not mean he literally altered the classics but metaphorically indicate that the stele text achieved a solemnity and grandeur equal to those ancient classics. From the piety of "fasted" to the creativity of "in a unique script", from the ritual of "bowed… on the vermilion steps" to the loyalty of "risking death", the poet constructs a sacred ritual of literary composition, portraying Han Yu as a cultural hero connecting imperial power, history, and the written word.

Stanza four

碑高三丈字如斗,负以灵鳌蟠以螭。

Bēi gāo sān zhàng zì rú dǒu, fù yǐ líng áo pán yǐ chī.

句奇语重喻者少,谗之天子言其私。

Jù qí yǔ zhòng yù zhě shǎo, chán zhī tiānzǐ yán qí sī.

长绳百尺拽碑倒,粗沙大石相磨治。

Cháng shéng bǎi chǐ zhuài bēi dǎo, cū shā dà shí xiāng mó zhì.

The stele stood thirty feet high, characters big as peck-measures; / Borne by a magic turtle, twined by hornless dragons. / Its lines were strange, its words weighty, few grasped their sense; / Slander reached the Son of Heaven, saying the writer was partial. / With a rope a hundred feet long they dragged the huge stele down; / Coarse sand and large stones were used to grind its face away.

The brush turns abruptly, depicting the calamity of the stele's destruction with highly impactful imagery. The colossal sense of "thirty feet high, characters big as peck-measures" contrasts shockingly with the violent destruction of "dragged the huge stele down." The line "Its lines were strange, its words weighty, few grasped their sense" encapsulates the historical tragedy where masterpieces are often misunderstood and loyal words slandered. The grating sound of "coarse sand and large stones" grinding symbolizes the brutal crushing of text by power and hints at the cruelty in the struggle for the right to narrate history.

Stanza five

公之斯文若元气,先时已入人肝脾。

Gōng zhī sīwén ruò yuánqì, xiān shí yǐ rù rén gānpí.

汤盘孔鼎有述作,今无其器存其辞。

Tāng pán Kǒng dǐng yǒu shùzuò, jīn wú qí qì cún qí cí.

呜呼圣皇及圣相,相与烜赫流淳熙。

Wūhū shèng huáng jí shèng xiàng, xiāngyǔ xuǎnhè liú chúnxī.

公之斯文不示后,曷与三五相攀追?

Gōng zhī sīwén bù shì hòu, hé yǔ sān wǔ xiāng pān zhuī?

愿书万本诵万过,口角流沫右手胝;

Yuàn shū wàn běn sòng wàn guò, kǒu jiǎo liú mò yòushǒu zhī;

传之七十有二代,以为封禅玉检明堂基。

Chuán zhī qīshí yǒu èr dài, yǐwéi fēngshàn yù jiǎn míngtáng jī.

This writing of the Duke was like Primordial Breath, / Which early on had entered people's livers and spleens. / On Tang's Basin and Confucius's Tripod were writings made; / Now the vessels are gone, but their words remain. / Alas! The sage emperor and sage minister, / Together shone resplendent, spreading pure light. / If this writing of the Duke is not shown to later ages, / How can their deeds be linked with the Three and Five Sovereigns? / I would transcribe ten thousand copies, recite it ten thousand times, / Though spittle froths my lips, my right hand grows a callus; / Pass it down through seventy-two generations, / To serve as the jade case for Feng and Shan rites, the Mingtang's foundation.

The final section erupts with a passion to defend historical truth and the dignity of the written word. The poet metaphorizes Han Yu's text as "Primordial Breath," saying its vitality has already merged into the nation's spiritual lifeblood. The analogy of "Tang's Basin and Confucius's Tripod" reveals the truth that material carriers can be destroyed, but the spirit remains immortal. The self-imposed vow, "I would transcribe ten thousand copies, recite it ten thousand times," displays the martyr-like will of a cultural guardian. Ultimately, the value of Han Yu's stele is elevated to the height of being the "jade case for Feng and Shan rites, the Mingtang's foundation"—not merely recording a temporary achievement but forming the cornerstone of orthodox Chinese historical narrative and cultural identity. This transcends judgment of a specific event, sublimating into an ultimate reflection on the relationship between writing, history, and civilizational transmission.

Holistic Appreciation

This is Li Shangyin's work whose imposing spirit most closely approximates Han Yu's vigor and originality. Its unique value lies in the triple symphony of discussing history, literature, and politics through poetry. The poem's structure is as grand as a stele: it begins with imperial majesty, elaborates in the middle on the entire process of the campaign, the composition, and the destruction, and concludes with a lament on civilizational transmission. The poet skillfully employs the elaborate exposition (fu) technique but avoids dull narration by using striking images like "A fierce wolf breeding chū," "emended phrases from the Canons of Yao and Shun," and "dragged the huge stele down," endowing the historical narrative with thrilling dramatic tension. Particularly profound is Li Shangyin's use of the fate of Han Yu's stele to reveal a central contradiction of the mid-Tang and indeed the entire imperial era: Behind the struggle for the right to historical writing lies the complex contest among political power, military glory, and cultural discourse. Ultimately, the poet stands from the height of cultural permanence, declaring that "coarse sand and large stones" cannot grind away true writing imbued with "Primordial Breath."

Artistic Merits

- Exemplary Fusion of Prose into Poetry: Incorporating the prose techniques of Han Yu, with uneven, cadenced syntax (e.g., "The emperor said, 'Du, your merit is first; / Your subordinate, Yu, should compose the text.'") and archaic, resonant diction (e.g., "shone resplendent," "pure light"), creating a solemn, epigraphic quality reminiscent of metal and stone.

- Binary Opposition of Imagery Systems: Constructs multiple sets of contrasting images: the "fasted, sat in a small chamber" and "freely flowed his great brush" of creation versus the "rope a hundred feet long" and "coarse sand and large stones" of destruction; the stele text's "lines were strange, its words weighty" versus the slander's "saying the writer was partial"; the physical "stele down" versus the spiritual "entered people's livers and spleens." The theme is highlighted through this tension.

- Masterful Control of Narrative Rhythm: The suppression process is concise and swift, the stele-writing scene is richly detailed, the moment of destruction is shocking, and the reflective lyricism is vast and far-reaching, forming a perfect rhythm of "introduction — development — turn — conclusion."

- Deep Metaphor in Allusion: The allusion to "Tang's Basin and Confucius's Tripod" not only metaphorizes the immortality of writing but also subtly implies that true historical judgment often lags behind contemporary politics, requiring the test of time.

Insights

The core insight this work offers posterity concerns the eternal struggle among historical truth, power, and the responsibility of the writer. It warns us: historical narrative is never a transparent process of objective recording but a field where various forces contend. The destruction of Han Yu's stele, superficially a dispute over "merit is first," was in reality a struggle among different factions for the right to interpret history. However, Li Shangyin constructs in the poem a transcendent historical justice: true writing is like "Primordial Breath," capable of piercing the barriers of time, ultimately "entering people's livers and spleens." This reminds every writer: facing the pressure of power and the fog of the times, one should uphold the courage of "To what is right, men since old have yielded not," for the eternity words can reach far surpasses the solidity of stone steles. Simultaneously, this poem is also a summons to readers—amidst the cacophony of voices, learn to recognize those profound utterances that are "strange" and "weighty," and be wary of simplistic slanders that "reach the Son of Heaven, saying the writer was partial," for the transmission of civilization depends not only on the author's courage but also on the reader's insight and courage to penetrate the mists of history.

Poem translator

Kiang Kanghu

About the poet

Li Shangyin (李商隐), 813 - 858 AD, was a great poet of the late Tang Dynasty. His poems were on a par with those of Du Mu, and he was known as "Little Li Du". Li Shangyin was a native of Qinyang, Jiaozuo City, Henan Province. When he was a teenager, he lost his father at the age of nine, and was called "Zheshui East and West, half a century of wandering".