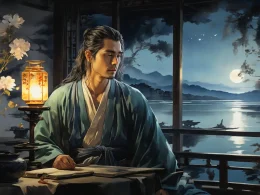

I had always heard of Lake Dongting --

And now at last I have climbed to this tower.

With Wu country to the east of me and Chu to the south,

I can see heaven and earth endlessly floating.

...But no word has reached me from kin or friends.

I am old and sick and alone with my boat.

North of this wall there are wars and mountains --

And here by the rail how can I help crying?

Original Poem

「登岳阳楼」

杜甫

昔闻洞庭水,今上岳阳楼。

吴楚东南坼,乾坤日夜浮。

亲朋无一字,老病有孤舟。

戎马关山北,凭轩涕泗流。

Interpretation

Composed in the winter of 768 AD during the final years of Du Fu's life, this poem was written after the poet had journeyed down from Kuizhou and spent a long period drifting along the rivers and lakes of the Jiang-Han region. By this time, advanced in age, he suffered from multiple ailments including a lung disease and partial paralysis, his hearing was deteriorating, and he lived in poverty. When this "aging, sick man in a solitary boat" reached Yueyang, he climbed alone the long-renowned Yueyang Tower. Facing the vastness of Dongting Lake, a lifetime of hardship, the loneliness of separation from friends and family, the afflictions of old age and sickness, and the persistent warfare in the north all converged and surged within him, crystallizing into this timeless masterpiece, acclaimed as the finest five-character regulated verse of the High Tang era.

First Couplet: 昔闻洞庭水,今上岳阳楼。

Xī wén Dòngtíng shuǐ, jīn shàng Yuèyáng lóu.

Long have I heard of Dongting Lake’s expanse; / Today I stand on Yueyang Tower’s heights.

The opening lines are deceptively simple, almost conversational, yet charged with profound temporal tension. Between "Long have I heard" and "Today I stand" lies a lifetime of the poet’s wanderings, yearnings, and hardships. This straightforward contrast not only relates the fulfillment of a long-held wish but also implies the deep melancholy of achieving it only in old age and adversity. Beneath a surface of fulfillment, an undercurrent of sorrow is already present.

Second Couplet: 吴楚东南坼,乾坤日夜浮。

Wú Chǔ dōng nán chè, qiánkūn rì yè fú.

It cleaves the lands of Wu and Chu, east and south; / Heaven and earth float, day and night, upon its waves.

With strokes as bold as a great beam, this couplet captures the lake’s awe-inspiring, cosmos-embracing grandeur. The verb "cleaves" conveys tremendous force and spatial vastness, while "float" lends a dynamic, almost magical quality, as if the sun, moon, and stars themselves drift upon its endless waters. The majestic vision and expansive scale of these lines are unparalleled. Yet, this very immensity accentuates the individual’s insignificance and solitude, foreshadowing the poignant shift that follows.

Third Couplet: 亲朋无一字,老病有孤舟。

Qīnpéng wú yī zì, lǎo bìng yǒu gū zhōu.

From kin and friends, not a single word; / In age and sickness, this lone boat is all I have.

The focus drops abruptly from cosmic vastness to the poet’s own diminished state, creating a heart-rending contrast. "Not a single word" speaks of utter isolation and severed ties in a chaotic world; "this lone boat is all I have" depicts the concrete reality of his final years—a boat as his only home, adrift and uncertain. The conjunction of "age and sickness" with "lone boat" renders his physical and spiritual desolation absolute. These fourteen syllables, each weighted with grief, form the most condensed and poignant summation of Du Fu’s late existence.

Fourth Couplet: 戎马关山北,凭轩涕泗流。

Róngmǎ guānshān běi, píng xuān tì sì liú.

War-charged steeds still press the northern frontier passes; / Leaning on the balcony rail, my tears and mucus flow.

From the depths of personal misery, the poet’s vision expands once more, transcending the self to confront the nation’s turmoil. "War-charged steeds still press the northern frontier passes" grounds the poem in its historical moment—the unceasing conflict, the unresolved peril. The visceral image of "Leaning on the balcony rail, my tears and mucus flow" is powerfully affecting. These flowing tears are shed not only for his own plight of "age and sickness… lone boat" but also for the suffering people and imperiled nation implied by "War-charged steeds… northern frontier." Personal sorrow and public anguish here become one; an old man at life’s end possesses a heart vast enough to hold the world’s pain.

Holistic Appreciation

This poem represents the culmination of Du Fu’s late poetic craft and moral character. Its power derives from "using a scene of supreme grandeur to offset a condition of extreme isolation; using a self in deepest anguish to express a concern of utmost breadth." The structure is masterfully orchestrated, the emotional arc dramatic: the first couplet begins with subdued fulfillment tinged with sorrow; the second soars into majestic, cosmic description; the third plummets to the nadir of personal misery; the fourth then merges the individual with the state, transforming private grief into a noble, universal lament.

The poem is built upon two core tensions: first, between the cosmic permanence of "Heaven and earth float, day and night" and the fragile transience of "In age and sickness, this lone boat." Second, between the large-scale upheaval of "War-charged steeds… northern frontier" and the intimate loneliness of "From kin and friends, not a single word." Du Fu’s greatness lies precisely in inhabiting this immense tension, bearing and ultimately transcending it through his frail person, achieving on Yueyang Tower a profound resonance between individual life and historical suffering.

Artistic Merits

- Expansive Vision and Stark Juxtaposition

The vast, cosmic imagery of "the lands of Wu and Chu" and "heaven and earth" is starkly juxtaposed with the minimal, frail elements of "a lone boat" and "age and sickness." This dramatic contrast in scale and circumstance creates a profoundly moving effect, quintessential of Du Fu's signature style—marked by somber depth and a powerfully measured rhythm. - Condensed Diction and Potent Conciseness

Not a word is superfluous. The third couplet, in particular, achieves an almost proverbial density: "From kin and friends, not a single word; / In age and sickness, this lone boat is all I have." In its extreme concision, it captures the complex depths of both personal and historical sorrow, where stark simplicity belies profound emotional weight. - Somber Emotional Depth and Masterful Pacing

The emotional arc of the poem moves from the quiet, almost resigned acknowledgment of the first couplet, through the awe inspired by the vast landscape in the second, plunges into the despair of the third, and culminates in the cathartic release of the fourth. This dynamic, undulating progression—both deeply felt and impeccably controlled—showcases the poet's consummate mastery over form and feeling in his final years. - Fusion of Personal and Public, Boundless Compassion

The poem seamlessly links the intimate lament of the third couplet with the national concern of the fourth, effecting a natural and powerful elevation. The poet's personal suffering is thus no longer a private complaint but is woven into the broader anguish of his era. This embodies his noble spirit, one that "dares not forget concern for the state, despite his lowly position."

Insights

This work reveals how a great spirit, at a moment of extreme personal hardship and vulnerability, can still engage with the immensity of the cosmos while holding the welfare of all people in his heart. In the dire straits of "age and sickness… this lone boat," Du Fu did not retreat into self-pity. Instead, within the majestic vista of "Heaven and earth float, day and night," he found a perspective that expanded his own spirit, and he resolutely fixed his gaze upon the distant strife of "War-charged steeds… the northern frontier."

The poem's most enduring lesson is this: True breadth of heart and vision is born not from triumph in favorable times, but precisely from endurance and transcendence in adversity. When personal destiny trembles like a "lone boat" on history's stormy seas, the defining choice lies between drowning in private sorrow or transforming one's own suffering into empathy for a broader human plight. This choice ultimately determines the stature of a life. In his final posture—leaning on the rail, tears flowing freely—Du Fu bequeaths to posterity an eternal exemplar: one who, amidst profound suffering, kept the world within his heart, and from a place of deep personal insignificance, never ceased to look up toward the heavens.

Poem translator

Kiang Kanghu

About the poet

Du Fu (杜甫), 712 - 770 AD, was a great poet of the Tang Dynasty, known as the "Sage of Poetry". Born into a declining bureaucratic family, Du Fu had a rough life, and his turbulent and dislocated life made him keenly aware of the plight of the masses. Therefore, his poems were always closely related to the current affairs, reflecting the social life of that era in a more comprehensive way, with profound thoughts and a broad realm. In his poetic art, he was able to combine many styles, forming a unique style of "profound and thick", and becoming a great realist poet in the history of China.