My heart is wrung with parting's pain;

If Heaven had a heart, 'twould age in vain.

How to define this woe?

Finer than silk, vaster than waves that flow.

My boat moors by the river's side,

Where maple leaves and reeds shiver autumn-tide.

Recalling joys now past and gone,

I see life's dream outshone by dawn.

Original Poem

「减字木兰花 · 伤怀离抱」

欧阳修

伤怀离抱,天若有情天亦老。

此意如何?细似轻丝渺似波。

扁舟岸侧,枫叶荻花秋索索。

细想前欢,须著人间比梦间。

Interpretation

The exact composition date of this lyric remains uncertain, though stylistic evidence suggests it belongs to Ouyang Xiu's early TianSheng period (1023-1032). As a young official navigating his first postings, the poet's emotional palette here reveals remarkable vulnerability—whether mourning a lover or kindred spirit, the verses pulse with undimmed authenticity across centuries. This work exemplifies the tender melancholy characteristic of his youthful ci poetry, where private grief achieves universal resonance.

First Stanza: "伤怀离抱,天若有情天亦老。此意如何?细似轻丝渺似波。"

Shāng huái lí bào, tiān ruò yǒu qíng tiān yì lǎo. Cǐ yì rú hé? Xì sì qīng sī miǎo sì bō.

This wounded heart,

This parting embrace—

Were Heaven capable of love,

Even it would age.

How to describe such feeling?

Fine as untwisted silk,

Vast as waves

With no shoreline.

The stanza opens with visceral physicality—the "wounded heart" and "parting embrace" establishing corporeal immediacy. The borrowed Li He line (天亦老) undergoes subtle transformation: where the Tang poet contemplated eternal sorrow, Ouyang personalizes cosmic grief. The dual simile (轻丝/渺波) performs emotional scaling, measuring intimacy against infinity.

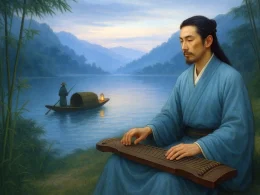

Second Stanza: "扁舟岸侧,枫叶荻花秋索索。细想前欢,须著人间比梦间。"

Piān zhōu àn cè, fēng yè dí huā qiū suǒ suǒ. Xì xiǎng qián huān, xū zhù rén jiān bǐ mèng jiān.

Moored skiff by the bank,

Maple leaves and reed plumes

Shivering in autumn's breath—

Remembered joys,

When examined closely,

Compel us to rank

The waking world

Below dreams.

The riverside tableau becomes an elegy in miniature: the "shivering" (索索) vegetation mirrors nervous-system tremors of grief. The epistemological crisis in the closing lines—where lived experience (人间) loses value against dreamt alternatives (梦间)—anticipates Zhuangzi's butterfly paradox by eight centuries. The boat's mooring (岸侧) symbolizes emotional stasis in temporal flow.

Holistic Appreciation

This lyric poem unfolds in two stanzas, each deepening the portrayal of post-separation sorrow with exquisite realism. The first stanza leans into lyrical lament—hyperbolic imagery like "the heavens aging" magnifies emotional weight, while rhetorical questions intensify the melancholic atmosphere. The second stanza grounds itself in tangible scenes: autumn vistas by the boat conjure bittersweet memories, starkly contrasting past warmth with present solitude. Here, the poet captures life’s cruel impermanence—the inevitability of parting and joy’s fleeting nature. Overflowing with restrained yet profound emotion, the poem embodies the classic Song dynasty wanyue (婉约) style: tender, lingering, and sorrowful without bitterness.

Artistic Merits

Blending scene and sentiment, the poem employs rhetorical questions and metaphors to craft a haunting aura of longing. Its structure orbits around yi (意, conceptual essence), unfolding through distinct techniques:

- Stanza 1 intensifies emotion via interrogation and figurative language—"gossamer threads on boundless waves" symbolize endless grief—while allusions (e.g., Li He’s famed lines) add philosophical depth, balancing sincerity with restraint.

- Stanza 2 merges feeling with landscape, using autumn imagery (lonely boats, maple leaves, reed flowers) to mirror human isolation. The closing contrast between "dream realm" and "mortal world" sharpens the ache of loss and nostalgia.

With concise language and harmonic rhythm, the poem epitomizes the lyrical subtlety and musicality of Song ci.

Insights

Through its plaintive cadence, the poem lays bare the agony of separation, revealing both the fragility and profundity of human bonds. It reminds us that true affection often shines brightest in farewells, and memories crystallize its worth. The poet’s clinging to love, resignation to reality, and idealization of dreams reflect universal emotional truths. Even when the "mortal world feels colder than dreams," the heart finds solace in reverie—perhaps this very recognition of "life’s harshness versus dreams’ tenderness" ensures the poem’s timeless resonance.

About the Poet

Ouyang Xiu (欧阳修, 1007 - 1072), a native of Yongfeng, Jizhou (present-day Jiangxi Province), emerged as the preeminent literary figure of the Northern Song Dynasty. After attaining the jinshi degree in 1030, he spearheaded a literary reform movement that rejected the ornate Xikun style prevalent at court. As a mentor who nurtured literary giants like Su Shi and Zeng Gong, he laid the foundation for the golden age of Northern Song literature. Recognized as one of the "Eight Great Prose Masters of Tang and Song," Ouyang stands as the pivotal figure in the transformation of Northern Song literary culture.