Clouds o'er Mount Song, trees of the western sky — how long have we lived apart!

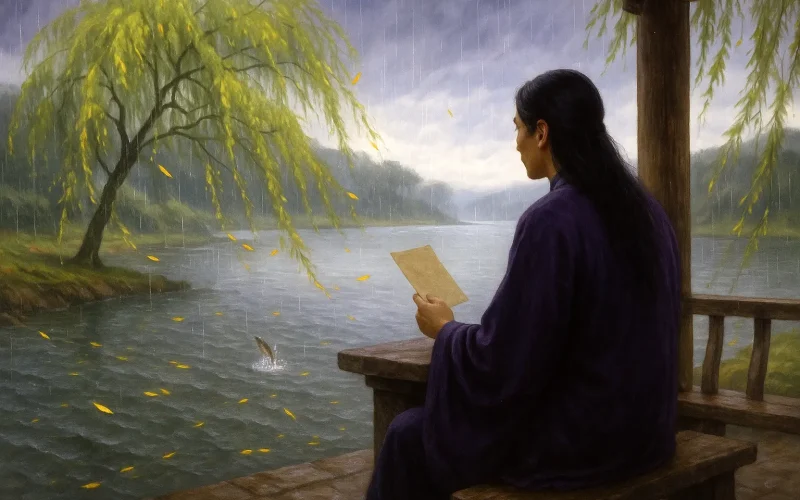

From you a letter brought by double carp has come, to cheer my lonely heart.

Do not ask about the old guest of the garden of the Prince of Liang —

I’m only like the sick Sima Xiangru in the autumn rain at Maoling.

Original Poem

「寄令狐郎中」

李商隐

嵩云秦树久离居,双鲤迢迢一纸书。

休问梁园旧宾客,茂陵秋雨病相如。

Interpretation

This poem was composed in the autumn of 845 AD, while Li Shangyin was residing in Luoyang during the mourning period for his deceased mother. This reply to a letter from Linghu Tao (then serving as Director of the Bureau of Honors) is, in essence, a cautious missive sent across a political rift. Nearly a decade had passed since the pivotal event in the Niu-Li factional strife—Li Shangyin's marriage to the daughter of Wang Maoyuan (in 838 AD). The estrangement between the poet and the Linghu family was by then a settled fact. Linghu Tao's letter was less a revival of personal friendship than a gesture of courtesy prompted by shifts in the political landscape (Emperor Wuzong was gravely ill, and the court's power structure was on the brink of change).

The poet's self-comparison in the line "At Maoling, autumn rains, a sick Sima Xiangru" carries three layers of contemporary resonance: first, the physical reality of his illness; second, his politically dormant state due to the mourning rite; and third, the spiritual "malady" forged within the crevices of factional conflict—an existential dilemma born of a lucid awareness of his own marginalization, coupled with the enforced necessity of silence. By this time, Li Shangyin understood his relationship with Linghu Tao with clear-eyed realism: the former intimacy of the "old guest of the Liang Garden" could never be restored, leaving only the spatial distance of "Mount Song's clouds, Qin's trees" and the psychological distance of an "ailing body in autumn rains."

First Couplet: 嵩云秦树久离居,双鲤迢迢一纸书。

Sōng yún Qín shù jiǔ lí jū, shuāng lǐ tiáotiáo yī zhǐ shū.

Mount Song's clouds, Qin's trees—long severed, we dwell apart; A single letter comes from afar, borne by twin carp.

Explication: "Mount Song's clouds, Qin's trees" uses geographical imagery to encapsulate a complex political geography: Mount Song refers to Luoyang (where the poet was in mourning), and Qin's trees refer to Chang'an (Linghu Tao's center of power). This separation by clouds and trees is not merely a natural vista but a visual metaphor for political affiliation—clouds drift without anchor, while trees stand rooted and firm, subtly reflecting the disparity in their situations. The word "long" in "long severed" implies the estrangement was not sudden but a structural condition formed over years. The phrase "borne by twin carp from afar" is masterfully crafted: letters conveyed by carp should be swift, yet "from afar" emphasizes the difficulty of traversing political divides, thereby underscoring the profound weight carried by this single sheet of paper.

Final Couplet: 休问梁园旧宾客,茂陵秋雨病相如。

Xiū wèn Liáng yuán jiù bīnkè, Màolíng qiūyǔ bìng Xiàngrú.

Ask not about that old guest of the Liang Garden days; At Maoling, autumn rains, a sick Sima Xiangru.

Explication: "Ask not" is the emotional pivot of the entire poem. Superficially a self-deprecating demurral, it is in truth a sorrowful entombment of a past relationship. The allusion to the Liang Garden (where Prince Xiao of Liang hosted literary men in the Western Han) carries a dual meaning here: it refers both to the poet's golden era of early patronage under Linghu Tao's father, Linghu Chu, and also suggests that the scholar's mode of survival—exchanging literary talent for political patronage—was now irrecoverable. The following line, comparing himself to "a sick Sima Xiangru at Maoling," is particularly profound. In his later years, Sima Xiangru pleaded illness and retired to Maoling, yet Emperor Wu still sent messengers to collect his writings. Through this allusion, Li Shangyin subtly indicates: although I lie ill in the autumn rains like Xiangru, you (Linghu Tao) are ultimately not Emperor Wu, and our relationship can never return to the pure, idealized state of a ruler seeking a writer's works. The autumn rains are not merely a natural phenomenon but a literary transmutation of the prevailing political chill.

Holistic Appreciation

This is a narrative of political sentiment articulated through a highly condensed, imagistic diplomacy. Within its twenty-eight characters, Li Shangyin constructs three dialogic layers: a geographical dialogue (Mount Song's clouds vs. Qin's trees), a temporal dialogue (past events at Liang Garden vs. present illness at Maoling), and a dialogue of identity (old guest vs. sick Sima Xiangru). Together, these layers point to a central quandary: in an environment where political factions have hardened, how is private friendship to be redefined and reconciled?

The poem's structure traces a precise trajectory of emotional retrenchment: from spatial distance (first couplet), to temporal separation (first line of final couplet), finally arriving at a transformed identity (second line of final couplet). This progression is not linear but a spiraling descent—each line confirms the predicament of the previous while uncovering a deeper stratum of alienation. By demoting himself from "old guest of the Liang Garden" (a literary participant with a social identity) to "sick Sima Xiangru at Maoling" (a marginalized, ailing individual), the poet effectively accomplishes a self-protective redefinition of identity: since he can no longer engage the power network under his former guise, he actively adopts the metaphorical identity of the "sick" to preserve his final vestige of dignity.

Particularly noteworthy is the subtle politics of "asking" embedded in the poem. "Ask not" superficially discourages inquiry but implicitly contains a preemptive judgment and rejection of what might be asked. In the context of late Tang factionalism, "questions" from the power center often carried political undertones. The poet's use of "ask not" severs this potential, an act of preserving self-respect and also a final, delicate demarcation of a relationship that has fundamentally changed—between us, profound conversation about the present is no longer fitting.

Artistic Merits

- The Political Transposition of Geographical Imagery: Mount Song (Luoyang) in the Tang was a typical retreat for officials in mourning or political disfavor, while the Qin region (Chang'an) was the empire's administrative heart. The choice of imagery—clouds and trees—is deeply significant: clouds (the poet) drift transiently, trees (Linghu) stand firmly rooted. This difference in natural attributes mirrors the inherent asymmetry of their political circumstances.

- The Self-Diminishing Use of Allusion: The "guest of the Liang Garden" was a glorious memory, but the poet seals it in the past with the word "old." Sima Xiangru was a literary genius, but the poet focuses on his "sick" and diminished state. This deliberate diminishment of luminous historical echoes is, in fact, an act of courage—stripping his personal situation of historical glamour to confront the cold reality of his present neglect.

- Political Metaphor in Climatic Description: "Autumn rains" are not merely descriptive but a literary crystallization of the late Tang political climate. The cold dampness of the rain, the desolation of autumn, compounded with the physiological reality of "sickness," create a synesthetic effect where natural atmosphere and political atmosphere merge, evoking a profound, bone-deep sense of the era's harshness.

Insights

This poem reveals a fundamental transformation of human relationships in an age of political division: when private friendship becomes entangled in factional logic, the most cherished memories can transform into the most painful present realities. The more beautiful the "old Liang Garden days" shared by Li Shangyin and Linghu Tao, the more starkly they highlight the bleakness of "autumn rains at Maoling." The lesson for any era is this: in a highly politicized environment, sustaining an old bond requires not only affection but also a clear-eyed recognition of its inevitable metamorphosis, and the graceful distance maintained in light of that recognition.

The complex wisdom contained in the words "ask not" is especially worthy of contemplation. It is not a blunt refusal but a careful delineation of relational boundaries—some questions, once posed, would expose fissures neither party can mend; some pasts, once revisited, would rupture a carefully preserved tranquility. This art of silent "non-asking" is the necessary, if painful, wisdom for safeguarding fragile connections within a politicized existence.

Ultimately, this poem demonstrates a mode of being within political interstices: using literary precision to map ambiguous emotional terrain; using the resonance of allusion to anchor the weightlessness of present circumstance. Li Shangyin does not complain or plead. He simply uses seven characters—"At Maoling, autumn rains, a sick Sima Xiangru"—to situate himself in a quiet corner of history's long gallery. There, no power struggles clamor, only the sound of autumn rain against the window and a poet who chooses the metaphor of sickness to guard his final dignity. This posture tells us: when external identity is reshaped by political forces, only an inner, literary self-possession can allow one to retain a fundamental composure amidst the storm.

About the poet

Li Shangyin (李商隐), 813 - 858 AD, was a great poet of the late Tang Dynasty. His poems were on a par with those of Du Mu, and he was known as "Little Li Du". Li Shangyin was a native of Qinyang, Jiaozuo City, Henan Province. When he was a teenager, he lost his father at the age of nine, and was called "Zheshui East and West, half a century of wandering".