Having long left hills and streams, how

I love to roam in woody place!

Coming with sons and nephews, now

Through hazels I see ruined trace.

I pace up and down on waste land

And find debris of dwellers old.

Marks of old wells and stoves still stand,

Dead branches are left in the cold.

I ask a woodman passing by,

If he knows who lived here before.

The woodman answers with a sigh,

"They are all dead and gone, no more."

Thirty years passed in town and court.

Everything has changed, it is true.

Life is a vision fair and short;

All will vanish into the blue.

Original Poem

「归园田居五首 · 其四」

陶渊明

久去山泽游,浪莽林野娱。

试携子侄辈,披榛步荒墟。

徘徊丘垄间,依依昔人居。

井灶有遗处,桑竹残杇株。

借问采薪者,此人皆焉如?

薪者向我言,死没无复余。

一世异朝市,此语真不虚。

人生似幻化,终当归空无。

Interpretation

Composed around 405 CE, this fourth poem in Tao Yuanming's "Returning to Dwell in Gardens and Fields" series reflects the poet's matured perspective after sustained reclusion. Through a journey with younger family members to abandoned ruins, Tao contemplates historical transitions and life's impermanence. While containing elegiac tones for the departed, the work ultimately reveals his philosophical understanding of life's illusory nature and ultimate return to emptiness—expressed with deceptively simple language that radiates profound wisdom.

First Couplet: "久去山泽游,浪莽林野娱。"

Jiǔ qù shān zé yóu, làng mǎng lín yě yú.

Long absent from mountain lakes, now I roam woods and wilds at leisure.

The opening reflects on Tao's official career ("long absent") before reclusion, with "at leisure" conveying hard-won contentment. The temporal marker "long" suggests deliberate rather than impulsive withdrawal.

Second Couplet: "试携子侄辈,披榛步荒墟。"

Shì xié zǐ zhí bèi, pī zhēn bù huāng xū.

Guiding sons and nephews, we part brambles through abandoned hamlets.

Family companionship ("sons and nephews") contrasts with desolate surroundings ("abandoned hamlets"), foreshadowing the meditation on transience.

Third Couplet: "徘徊丘垄间,依依昔人居。"

Pái huái qiū lǒng jiān, yī yī xī rén jū.

Wandering among burial mounds, lingering where ancestors dwelt.

"Lingering" (依依) conveys poignant attachment, while "burial mounds" make mortality tangible. The couplet bridges physical ruins and emotional memory.

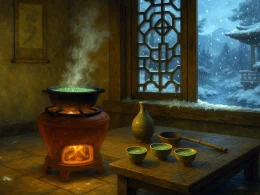

Fourth Couplet: "井灶有遗处,桑竹残杇株。"

Jǐng zào yǒu yí chù, sāng zhú cán wū zhū.

Well and hearth leave traces; mulberries and bamboos stand decayed.

Domestic relics ("well and hearth") and withered plants make time's erosion visceral, preparing for the existential questioning.

Fifth Couplet: "借问采薪者,此人皆焉如?"

Jiè wèn cǎi xīn zhě, cǐ rén jiē yān rú?

I ask a wood-gatherer: "Where have all these people gone?"

The colloquial question—ordinary yet profound—transforms observation into philosophical inquiry about human transience.

Sixth Couplet: "薪者向我言,死没无复余。"

Xīn zhě xiàng wǒ yán, sǐ mò wú fù yú.

The gatherer replies: "Dead—none remain."

The matter-of-fact response delivers existential weight, its brevity underscoring life's fragility.

Seventh Couplet: "一世异朝市,此语真不虚。"

Yī shì yì cháo shì, cǐ yǔ zhēn bù xū.

"A generation changes markets and courts"—how true these words.

Tao recognizes historical cycles intellectually before internalizing their personal meaning.

Eighth Couplet: "人生似幻化,终当归空无。"

Rén shēng shì huàn huà, zhōng dāng guī kōng wú.

Human life resembles illusions—ultimately returning to void.

The climactic insight transcends melancholy, achieving serene acceptance of nature's cycles.

Holistic Appreciation

The poem progresses from scenic observation to existential revelation. Beginning with family excursion details, it uses ruined habitats and a woodcutter's testimony to confront mortality. The language remains unadorned yet resonant, particularly the final couplet's distillation of Tao's worldview: "Human life resembles illusions—ultimately returning to void." This represents neither nihilism nor despair, but enlightened reconciliation with life's ephemeral nature—a hallmark of Tao's mature philosophy.

Artistic Merits

This poem demonstrates Tao's signature plain yet profound language, with a structure that progresses from concrete observations to abstract philosophy. The poet masterfully transforms ordinary life scenes—particularly the woodcutter's dialogue—into profound meditations, creating an emotional and intellectual climax. While the concluding lines may appear stark, they encapsulate the essence of Tao's worldview: harmony with nature, transcendence over life and death, and the pursuit of inner peace.

Insights

With clear-eyed composure, the poet contemplates the cycles of human affairs and life's ultimate dissolution, gently conveying the realization that "life is but illusion." This serene and magnanimous attitude toward life encourages us to release attachments, cherish the present moment, and reminds us that only through inner clarity can we navigate worldly vicissitudes with equanimity.

Poem translator

Xu Yuanchong (许渊冲)

About the poet

Tao Yuanming(陶渊明), 365 – 427 CE, was a poet, literary figure, fu writer, and essayist active during the late Eastern Jin and early Liu Song dynasties. Born in Chaisang (near present-day Jiujiang, Jiangxi Province), he pioneered a new genre of pastoral-themed literature, expressing profound philosophical insights through simple language. His poetic style became an enduring aesthetic standard in classical Chinese poetry.