Now that the palace-gate has softly closed on its £lowers, Ladies file out to their pavilion of jade, Abrim to the lips with imperial gossip But not daring to breathe it with a parrot among them.

Original Poem

「宫词」

寂寂花时闭院门,美人相并立琼轩。

含情欲说宫中事,鹦鹉前头不敢言。

Interpretation

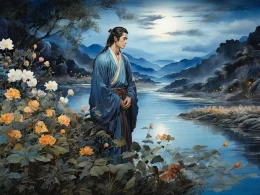

This "A Song of the Palace" was composed in the late Tang Dynasty by Zhu Qingyu, a key representative of mid-to-late Tang palace-style poetry known for his delicate portrayals of palace women's lives and inner emotions. Under the rigid Tang imperial system, countless talented and beautiful consorts languished in lifelong solitude. Through such lyrics, Zhu gave voice to these historically marginalized women. Though brief—just twenty characters—the poem condenses profound melancholy, oppression, and helplessness, laying bare the tragic plight of women under feudal power structures.

First Couplet: "寂寂花时闭院门,美人相并立琼轩。"

Jì jì huā shí bì yuàn mén, měi rén xiāng bìng lì qióng xuān.

In flower-laden spring, courtyard gates stay locked and still;

Two beauties stand side by side beneath jade-trimmed eaves.

The juxtaposition of "flower-laden spring" with "locked and still" creates stark contrast between the vibrant world outside and the suffocating stillness within the palace walls. Closed gates symbolize the women's imprisonment, while their poised stance under ornate corridors—though visually elegant—conveys abandonment and mutual dependence, their glamour devoid of joy.

Second Couplet: "含情欲说宫中事,鹦鹉前头不敢言。"

Hán qíng yù shuō gōng zhōng shì, yīng wǔ qián tou bù gǎn yán.

Longing to share their sorrows, yet lips stay sealed—

Before the parrot's perch, no word escapes their grief.

This couplet delivers the poem's devastating punchline. Though desperate to confide in each other, even in seemingly private moments they dare not speak freely. The parrot, typically a pet, here becomes a symbol of surveillance and betrayal—its mimicry threatening exposure. Zhu masterfully embeds social critique within scenery, exposing the palace's cruelty through what remains unspoken. The deepest sorrow lies not in suffering, but in the inability to voice it.

Holistic Appreciation

Though concise, this poem is rich in layers and profound in emotion. It begins with the setting—images of blooming flowers and jade-adorned balconies—which starkly contrasts with the words "silent" and "closed doors," highlighting the spiritual desolation of palace women amid material luxury. The image of "two maids standing side by side" conveys their loneliness and mutual solace, while the climactic line—"Before the parrot, they dare not speak"—cuts abruptly into suppressed anguish, transforming the scene into a silent indictment.

Zhu Qingyu avoids direct lamentation. Instead, through a tranquil scene and a personified parrot, he captures the maids’ hyperawareness and self-censorship under confinement, making their sorrow implicit yet deeply resonant. The poem is visual yet sonically evocative, sorrowful yet restrained, achieving remarkable artistic power.

Artistic Merits

Exemplifying the principle "reveal grandeur through minutiae" and "channel emotion through scenery," the poem is linguistically elegant and emotionally understated, packing profound meaning into minimal lines. Zhu employs a symmetrical composition—"two figures standing together"—to generalize loneliness into a collective plight, intensifying the pathos. The greatest tension lies in the parrot line, where an object (bird) becomes a narrative device, creating a suffocating atmosphere. This showcases the pinnacle of Late Tang palace poetry’s emotional craftsmanship.

Insights

With utmost restraint, this poem voices the heaviest grief, exposing lives and emotions crushed beneath power and opulence. Today, it still urges us to heed voices stifled by systems and environments—those "words swallowed back" and "silence before parrots" belong not only to historical maids but to anyone oppressed in high-pressure settings. It reminds us that the deepest pain often stems not from being unable to speak, but from losing even the freedom to express.

Poem translator

Kiang Kanghu

About the Poet

Zhu Qingyu (朱庆馀, dates unknown), a native of Shaoxing, Zhejiang, was a Mid-Tang dynasty poet who attained the jinshi degree in 826. A master of five-character regulated verse (wulü), his poetry is characterized by delicate restraint and lyrical subtlety—refining Zhang Ji's style with greater refinement. The critic Yan Yu praised him as "graceful yet profoundly evocative, a virtuoso of the Mid-Tang," positioning him as a transitional figure between the Dali and Yuanhe poetic eras.