Peach Brook denied us lingering grace,

Fall's lotus stems—no suture to retrace.

That year we met at Scarlet Balustrade,

Now I stalk gold-leaf ruins alone.

Smoke scrolls unfold blue peaks unread,

Geese ferry crimson dusk to deathbed.

You: cloud-stuff drowned in river's throat,

I: rain-sodden fluff stuck to mud's note.

Original Poem

「玉楼春 · 桃溪不作从容住」

周邦彦

桃溪不作从容住,秋藕绝来无续处。

当时相候赤阑桥,今日独寻黄叶路。

烟中列岫青无数,雁背夕阳红欲暮。

人如风后入江云,情似雨馀粘地絮。

Interpretation

Composed in 1089 during Zhou Bangyan's tenure as Prefectural Professor in Luzhou, this ci poem was written on the eve of his departure from Taoxi (Peach Blossom Stream). Revisiting old haunts stirred memories of a vanished romance—perhaps real, perhaps imagined—that haunts the poem's exquisite imagery. Through masterful allusions and symbolic landscapes, Zhou articulates profound attachment and resignation, revealing a melancholic depth beyond his typical "elegant restraint." The work stands as a pinnacle of Song dynasty lyrical poetry, where every couplet balances classical allusion with psychological immediacy.

First Stanza: "桃溪不作从容住,秋藕绝来无续处。当时相候赤阑桥,今日独寻黄叶路。"

Táo xī bù zuò cóng róng zhù, qiū ǒu jué lái wú xù chù. Dāng shí xiāng hòu chì lán qiáo, jīn rì dú xún huáng yè lù.

At Peach Stream, no lingering stay—

autumn lotus severed beyond repair.

Then we met by vermilion railings,

now I walk alone through gold-leafed lanes.

The opening couplet weaves myth and metaphor. "Peach Stream" (桃溪) invokes the legend of Liu Chen and Ruan Zhao's fairy encounter—a conventional symbol for ephemeral love—while "autumn lotus severed" (秋藕绝) subverts the common "lotus threads remain" love trope to emphasize irrevocable rupture. The spatial contrast between "vermilion railings" (赤阑桥), vibrant with past intimacy, and "gold-leafed lanes" (黄叶路), autumnal and solitary, maps emotional desolation onto physical geography. Zhou's genius lies in making seasonal decay (autumn leaves) and architectural details (railings, lanes) bear the weight of vanished joy.

Second Stanza: "烟中列岫青无数,雁背夕阳红欲暮。人如风后入江云,情似雨馀粘地絮。"

Yān zhōng liè xiù qīng wú shù, yàn bèi xī yáng hóng yù mù. Rén rú fēng hòu rù jiāng yún, qíng sì yǔ yú nián dì xù.

Misty peaks stack endless blue,

geese bear sunset's dying glow.

You: river-clouds scattered by wind;

my love: willow down glued to rain-soaked earth.

The concluding stanza ascends to metaphysical vision. The "misty peaks" (烟中列岫) and "sunset geese" (雁背夕阳) construct a sublime backdrop for existential meditation. The paired similes—"river-clouds scattered" versus "willow down glued"—create devastating emotional physics: the beloved's disappearance into airy nothingness contrasts with the speaker's clinging attachment, heavy as waterlogged floss. The "willow down" (絮) image particularly dazzles—ephemeral yet stubbornly earthbound, it embodies love's paradox: weightless in essence but impossible to shake off.

Holistic Appreciation

This ci orchestrates a symphony of temporal and spatial dissonance. The first stanza's horizontal movement—from stream to bridge to lane—traces love's trajectory from confluence to separation, while the second stanza's vertical imagery of peaks, geese and clouds elevates personal loss to cosmic scale. Zhou's compositional brilliance shines in his counterpoint of chromatic progression, where vermilion (赤) shifts to gold (黄) then blue (青) and finally sunset red (红), mapping passion's gradual cooling through color symbolism. The elemental balance between water (stream, rain) and air (clouds, wind) grounds abstract emotions in natural forces, while layered temporalities—mythic past (Peach Stream legend), personal past (railings meeting) and desolate present (leaf-strewn path)—create profound historical resonance.

The poem's emotional power derives from its remarkable restraint—nowhere does Zhou explicitly name "love" or "sorrow." Instead, he lets a broken lotus stem and rain-heavy floss speak volumes, proving that true profundity often resides in quiet observation rather than loud declaration. Through this subtle interplay of movement, color and elemental imagery, Zhou transforms personal heartbreak into a universal meditation on love's ephemerality and memory's persistence.

Artistic Merits

- Botanical symbolism

The autumn lotus (秋藕) and willow down (絮) transform plants into emotional barometers, continuing the Chu Ci tradition of floral metaphor. - Cinematic contrast

The shift from warm "vermilion railings" to cold "gold-leafed lanes" creates visual storytelling worthy of modern film transitions. - Kinetic metaphors

"Scattered by wind" (风后入江云) versus "glued to earth" (雨馀粘地絮) enact emotional dynamics through nature's movements. - Mythic resonance

The Peach Stream allusion (桃溪) elevates personal memory to archetypal romance, universalizing the experience.

Insights

Zhou's poem reveals a fundamental truth about human attachment: that love's aftermath often leaves us simultaneously unmoored ("scattered clouds") and paralyzed ("glued floss"). This paradox—of feeling both weightless and weighed down—finds perfect expression in his natural metaphors.

For contemporary readers, the work demonstrates how profound loss can be conveyed through environmental details rather than emotional outbursts. The "gold-leafed lanes" and "rain-soaked earth" model a poetic approach to grief—one that finds solace in nature's cycles while acknowledging pain's stubborn persistence.

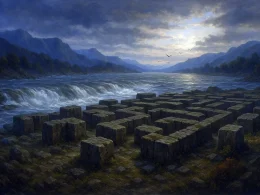

Ultimately, the poem suggests that certain loves become landscapes. The vermilion bridge and peach stream remain long after the lovers depart, just as our most meaningful relationships imprint themselves onto physical spaces, transforming geography into memory's theater. Zhou's genius lies in making these impressions visible—not through explanation, but through quiet, devastating observation.

About the Poet

Zhou Bangyan (周邦彦 1056 - 1121), a native of Qiantang (modern Hangzhou, Zhejiang), was the culminating master of the wanyue (graceful and restrained) ci poetry of the Northern Song Dynasty. A virtuoso in musical temperament, his ci are renowned for their opulent refinement and technical perfection. He created dozens of new melodic patterns (cipai) and adhered to strict tonal rules, earning him the title "Crown of Ci Poets." His influence extended to Southern Song masters like Jiang Kui and Wu Wenying, establishing him as the founding patriarch of the Rhymed Ci School.