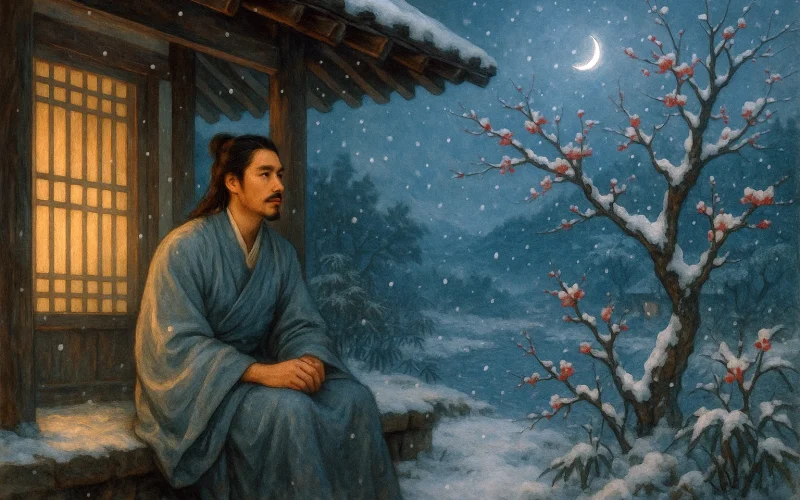

Night's heat persists like noon's fierce blaze,

I stand by the door in moonlit haze.

Where bamboo thick and trees entwine with insect song,

A subtle coolness steals—though no wind blows along.

Original Poem

「夏夜追凉」

杨万里

夜热依然午热同,开门小立月明中。

竹深树密虫鸣处,时有微凉不是风。

Interpretation

Composed around the fourth year of the Qiandao era under Emperor Xiaozong of Song (1169 AD). At that time, Yang Wanli, having passed the age of forty, had resigned from official duties and was living in leisure. He often took nighttime strolls, admired the moon, and sought coolness in his hometown. This heptasyllabic quatrain was an impromptu composition born from his nocturnal pursuit of relief from the heat. Rather than emphasizing the daytime's scorching temperatures, the poet focuses on the subtle experience of coolness at night. Through concise and refreshing description, he interweaves the moonlight, bamboo groves, insect choruses, and the essence of stillness into a uniquely evocative tableau, reflecting his deep affection for nature and refined sensitivity.

First Couplet: "夜热依然午热同,开门小立月明中。"

Yè rè yīrán wǔ rè tóng, kāi mén xiǎo lì yuè míng zhōng.

The night's heat remains identical to the noon's; unable to sleep due to the extreme swelter, the poet pushes the door open and steps out, standing briefly alone within the radiant moonlight.

Here, the parallel structure of "noon heat" (午热 wǔ rè) and "night heat" (夜热 yè rè) intensely conveys the lingering, inescapable 暑气 (shǔqì, summer heat), crafting a stifling and oppressive atmosphere. Yet the poet expresses no bitter resentment; instead, the act of "opening the door and standing briefly" (开门小立 kāi mén xiǎo lì) presents a stance of feigned detachment and 从容自适 (cóngróng zìshì, composed ease). The emergence of the bright moon further embellishes the scene with 清光 (qīngguāng, clear light) and 静谧 (jìngmì, tranquility). What the poet seeks is not mere physical coolness but rather, through the 夜色 (yèsè, nightscape) and 月光 (yuèguāng, moonlight), a means to temper the intense heat, thereby clarifying his mental state.

Second Couplet: "竹深树密虫鸣处,时有微凉不是风。"

Zhú shēn shù mì chóng míng chù, shí yǒu wēi liáng bù shì fēng.

From where the bamboos are deep and trees dense, and insects chirp, a slight coolness emerges at times, yet it is not the wind.

This couplet uses the environment to 烘托 (hōngtuō, set off) the 意境 (yìjìng, artistic conception). "Bamboos deep, trees dense" (竹深树密 zhú shēn shù mì) highlights the 清幽 (qīngyōu, secluded serenity), while "where insects chirp" (虫鸣处 chóng míng chù) manifests a profound 宁静 (níngjìng, tranquility). The concluding statement "not is wind" (不是风 bù shì fēng) is profoundly meaningful: this thread of coolness originates from the deepening night and the gradual clearing of the air's essence (气息渐清 qìxī jiàn qīng), not from any external wind. The poet acutely captures this subtle experience of "coolness born from stillness" (静中生凉 jìng zhōng shēng liáng), transforming an ordinary sensation into a poetic 境界 (jìngjiè, realm), showcasing the wondrous fusion of heart and nature.

Holistic Appreciation

The poem's subtlety lies in its technique of "conveying pervasive heat without using the word, generating coolness without directly describing it" (不着热字而全见热,不写凉意而处处生凉). The poet skillfully employs 侧笔 (cèbǐ, indirect description) and 留白 (liúbái, strategic omission) to contrast the summer night's heat and coolness. The first half addresses the heat, the second the coolness; progressing from the solitary figure "opening the door and standing briefly" to the secluded atmosphere of "bamboos deep, trees dense," and finally to the philosophical revelation of "not is wind," the poetic 境界 (jìngjiè, realm) advances layer by layer. This illustrates the process from 燥热 (zàorè, sweltering heat) to 清凉 (qīngliáng, refreshing coolness), from the external environment (外境 wàijìng) to the internal state of mind (心境 xīnjìng).

This approach of "avoiding the solid for the ethereal" (避实就虚 bì shí jiù xū) encapsulates the charm of classical poetry: it achieves depth not through ornate diction but within a framework of 清简 (qīngjiǎn, clarity and simplicity), refracting 生活的真实 (shēnghuó de zhēnshí, the truth of life) and 哲思的深邃 (zhésī de shēnsuì, the depth of philosophical thought). It leaves a lasting, evocative impression, making the reader feel as if standing beside the poet under the summer moon, quietly observing the breath of heaven and earth.

Artistic Merits

- Drawing material from natural life: It depicts the ordinary activity of enjoying the coolness at night, yet reveals profound genuine emotion through meticulous details.

- Evoking the intense by depicting the cool: It masterfully sidesteps direct description of the sweltering heat, instead focusing on the "pursuit of coolness" (追凉 zhuī liáng), thereby creating a potent and clever contrast.

- Fusion of scene and emotion: Scenery such as moonlight, dense bamboo groves, and insect chirps accentuate the state of stillness and the sense of coolness.

- Meticulous observation: The line "is not the wind" (不是风 bù shì fēng), in particular, reveals the poet's extraordinary, acute sensitivity.

- Fresh and natural language: The poem's language is plain and lively, yet possesses an endlessly evocative quality.

- Implicit philosophical depth: The concept of "coolness born from stillness" (静中生凉 jìng zhōng shēng liáng), though never explicitly stated, becomes self-evident through the poetic 境 (jìng, realm).

Insights

This poem reveals that beauty and comfort in life need not always depend on external objects but often arise from the harmony between one's state of mind (心境 xīnjìng) and the environment. Even amidst intense heat, a calm and peaceful heart (心静自安 xīn jìng zì ān) can perceive subtle coolness. Yang Wanli's verse reminds us that poetry resides in the minute details, and within the ordinary, one can discover life's beauty and refreshing clarity.

About the Poet

Yang Wanli (杨万里 1127 - 1206), a native of Jishui in Jiangxi, was a renowned poet of the Southern Song Dynasty, celebrated as one of the "Four Great Masters of the Restoration" alongside Lu You, Fan Chengda, and You Mao. He attained the jinshi degree in 1154 and rose to the position of Academician of the Baomo Pavilion. Breaking free from the constraints of the Jiangxi School of Poetry, he pioneered the lively and natural "Chengzhai Style," advocating for learning from nature and employing plain yet profound language. His poetry, often drawing inspiration from everyday life, profoundly influenced later schools of lyrical expression, particularly the Xingling (Spirit and Sensibility) School.