Pearl pins fixed—I chide the wanton air,

Where Song’s wall guards painted pleasure’s lair.

Orchids’ grudge dyes each stem jade-green,

Peaches’ mute lust flames unseen.

Swallows twine where silk veils furl,

Orioles whine where gold halls whirl.

That fickle boy—whose bed tonight?

My dreams reclaim his phantom light.

Original Poem

「舞春风」

冯延巳

严妆才罢怨春风,粉墙画壁宋家东。

蕙兰有恨枝尤绿,桃李无言花自红。

燕燕巢儿罗幕卷,莺莺啼处凤楼空。

少年薄幸知何处,每夜归来春梦中。

Interpretation

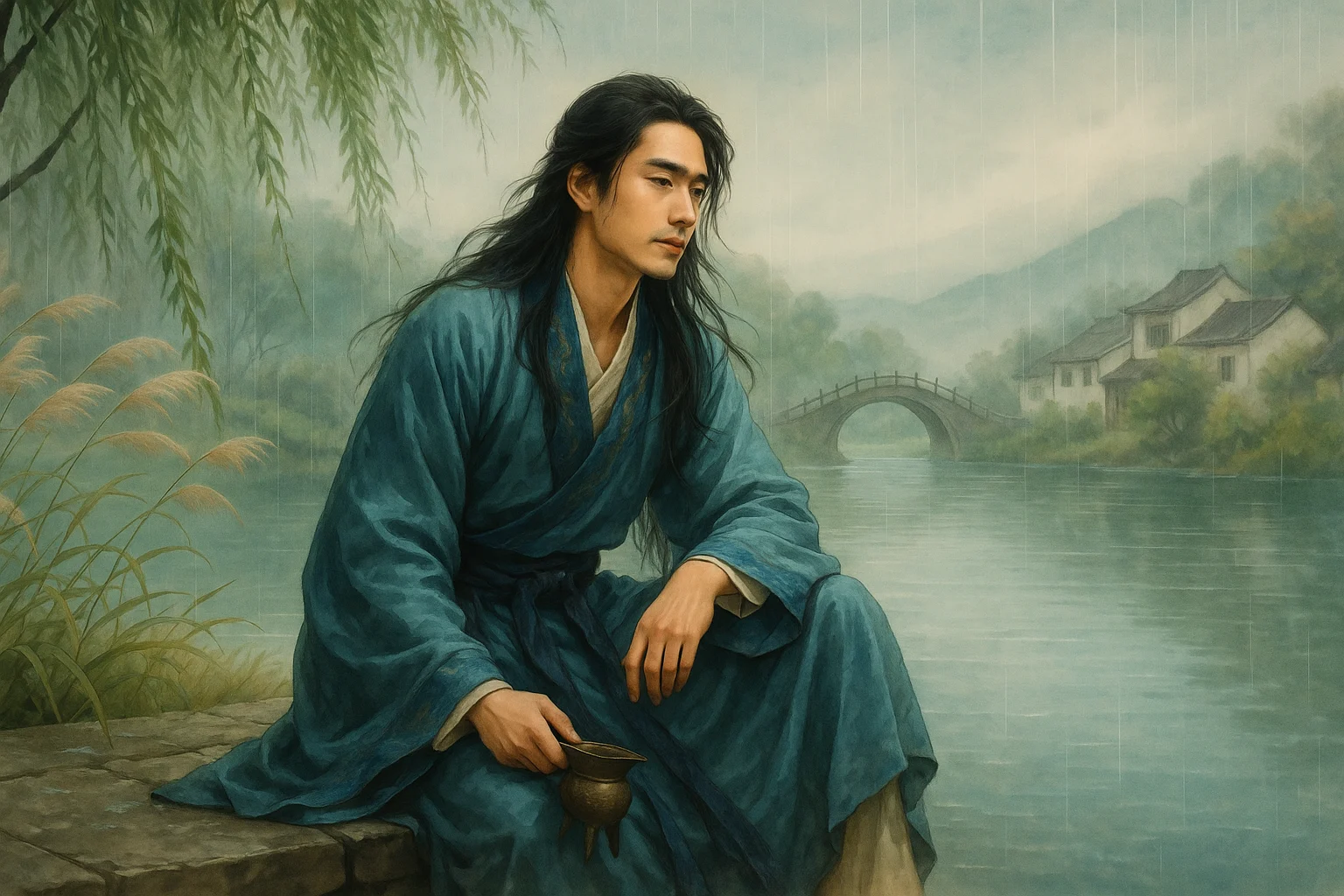

Composed during the Southern Tang dynasty—a brief but culturally vibrant interlude between the Tang and Song eras—this regulated verse exemplifies Feng Yansi's literary mastery. As a prominent figure valued by both Emperor Zhongzhu Li Jing and the later Emperor Li Yu, Feng blended scholarly refinement with political insight. While his works often adopt feminine personas to explore romantic longing, they subtly convey his own meditations on fate, political disillusionment, and life's impermanence.

This poem, ostensibly portraying a woman's yearning and melancholy, serves as a metaphorical canvas for the poet's own emotional and intellectual landscape. Against the backdrop of Southern Tang's political turbulence, the "boudoir lament" became a covert medium for literati to express personal and collective anxieties. Feng's adept use of the female perspective not only demonstrates his psychological acuity but also marks the transition from Five Dynasties' stylistic directness to the Song dynasty's nuanced subtlety.

First Couplet: "严妆才罢怨春风,粉墙画壁宋家东。"

Yán zhuāng cái bà yuàn chūn fēng, fěn qiáng huà bì Sòng jiā dōng.

Fresh from solemn adornment, she blames the spring breeze—

By painted walls east of the Song estate, her discontent takes root.

The opening lines immediately establish the protagonist's conflicted state: her meticulous grooming ("solemn adornment") contrasts sharply with her resentment toward the spring breeze—an emblem of stirring desires. The setting, "east of the Song estate," hints at aristocratic seclusion, where ornate walls ("painted walls") symbolize both privilege and confinement.

Second Couplet: "蕙兰有恨枝尤绿,桃李无言花自红。"

Huì lán yǒu hèn zhī yóu lǜ, táo lǐ wú yán huā zì hóng.

Orchids nurse grief, yet their stems stay verdant;

Peach and plum, though silent, blush unabashed.

This couplet employs floral metaphors to articulate the woman's inner world. The orchids (蕙兰), representing noble but sorrowful beauty, retain their vitality despite hidden anguish. The peach and plum blossoms (桃李), symbols of unspoken allure, flourish independently of admiration. Here, nature's resilience mirrors the woman's quiet dignity amid neglect.

Third Couplet: "燕燕巢儿罗幕卷,莺莺啼处凤楼空。"

Yàn yàn cháo ér luó mù juǎn, yīng yīng tí chù fèng lóu kōng.

Swallows nest behind rolled-up silken drapes,

While orioles sing to an empty phoenix tower.

Spring's vitality—embodied by nesting swallows and singing orioles—sharpens the contrast with the deserted "phoenix tower" (凤楼), a traditional metaphor for women's quarters. The imagery of movement (nesting, singing) against stillness (emptiness) amplifies the woman's isolation, rendering her solitude palpable.

Fourth Couplet: "少年薄幸知何处,每夜归来春梦中。"

Shào nián bó xìng zhī hé chù, měi yè guī lái chūn mèng zhōng.

That fickle youth—where does he roam now?

Nightly, he returns only in springtime dreams.

The finale crystallizes the poem's emotional core: the woman's mingled longing and reproach for the absent "fickle youth" (薄幸). The recurring dream motif underscores the paradox of presence-in-absence, where nocturnal visitations heighten daytime desolation. This conclusion, steeped in the wanyue tradition, balances tender vulnerability with unresolved ache.

Holistic Appreciation

This poem portrays the longing and sorrow of a secluded woman, unfolding her inner melancholy through the scenery of her boudoir and the tokens of spring. The opening line, "Resenting the spring breeze," immediately establishes her plaintive mood, while the following lines—comparing herself to orchids, peach blossoms, and plum trees—deepen the emotion with restrained tenderness. The desolate imagery of the empty chamber further accentuates her solitude, and the final couplet, depicting a dream of love, crescendos the emotional intensity. Though the word "sorrow" never appears, every line resonates with it, rendered in an elegant, lingering style.

Artistic Merits

- Emotion Through Imagery, Scene and Sentiment Intertwined

The poet masterfully employs motifs like the spring breeze, orchids, peach blossoms, orioles, and phoenix towers to craft a vivid spring tableau suffused with sorrow. The lonely woman’s emotions are projected onto nature, creating a profound, echoing beauty. - Linguistic Grace and Feminine Nuance

Phrases like "still green," "blushing alone," "nesting birds," and "where they cry" carry a soft, lyrical cadence, emphasizing the delicate, feminine touch. The direct yet poignant line "Where has that fickle youth gone?" strikes a balance between sorrow and restraint, reminiscent of Li Yu’s "sad but not despairing" aesthetic. - Structural Sophistication

The four couplets progress from external observation to internal reflection, from subdued emotion to candid lament, demonstrating masterful control of the regulated verse form. While rooted in the traditional "boudoir lament" genre, the poem transcends mere sentimentality, offering tension and empathy—a gem among Five Dynasties poetry.

Insights

On the surface, this poem depicts a secluded woman’s resentment toward an unfaithful lover, but it also speaks to broader themes of love and human nature. It reveals how traditional literature could use the "other" (here, a female voice) as a vessel for the poet’s own emotional projection. Feng Yansi, through this feminine persona, captures the nuanced pain of lost love, showcasing not only psychological insight but also a deep reverence for genuine affection.

For modern readers, the poem serves as a reminder: the deepest heartbreak often stems not from fiery conflict but from silent drifting apart; the most profound devotion may linger only in the phantom of a dream. Literature’s power lies in its ability to crystallize these ineffable emotions into timeless verse, echoing across the river of time. This is both an artistic achievement and a testament to emotional truth.

About the Poet

Feng Yansi (冯延巳 903 - 960), courtesy name Zhengzhong, was a native of Guangling (modern-day Yangzhou, Jiangsu) and a renowned ci poet of the Southern Tang during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. Rising to the position of Left Vice Director of the Department of State Affairs (Zuo Puye Tongping Zhangshi), he enjoyed the deep trust of Emperor Li Jing. His ci poetry forged a new path beyond the Huajian tradition, directly influencing later masters like Yan Shu and Ouyang Xiu, playing a pivotal role in the transition of ci from "entertainment for musicians" to "literary expression of scholar-officials."