Burning eaglewood smothers humid days,

Sparrows broadcast clear-dawn alerts through haze.

New sun bakes night-rain off leaves—

Water polishes discs,

Wind tilts lotus into perfect slopes.

Homeland's a lost coordinate,

Why linger in Chang'an's alien state?

Do May fishermen still recall

Our light oars, our dream's protocol—

That inlet where lotuses scroll?

Original Poem

「苏幕遮 · 燎沉香」

燎沉香,消溽暑。鸟雀呼晴,侵晓窥檐语。

叶上初阳干宿雨,水面清圆,一一风荷举。故乡遥,何日去?家住吴门,久作长安旅。

周邦彦

五月渔郎相忆否?小楫轻舟,梦入芙蓉浦。

Interpretation

Composed between 1083-1086 during Zhou Bangyan's tenure at the Imperial Academy in Bianjing (Kaifeng), this ci poem emerges from a period of professional frustration and homesickness. Though recognized for his literary talents, Zhou felt constrained by unmet ambitions, channeling his displacement into this summer lotus pond scene—a lyrical bridge between Northern Song capital life and his cherished Jiangnan homeland. The work transforms seasonal observation into a meditation on bureaucratic stasis and geographic longing, marking a pivotal moment in his poetic maturation.

First Stanza: "燎沉香,消溽暑。鸟雀呼晴,侵晓窥檐语。"

Liáo chén xiāng, xiāo rù shǔ. Niǎo què hū qíng, qīn xiǎo kuī yán yǔ.

Aloeswood incense coils—

damp summer heat dispelled.

Sparrows herald clearing skies,

at dawn they peep beneath eaves, chirping.

The opening establishes a private microclimate where aromatic defense ("aloeswood incense") battles climatic oppression ("damp summer heat"). The sparrows' weather prophecy ("herald clearing skies") introduces avian agency, their eavesdropping presence ("peep beneath eaves") lending the scene domestic vitality. This interplay—human ritual versus animal spontaneity, indoor refuge versus outdoor renewal—prefigures the poem's central tension between capital confinement and southern yearning.

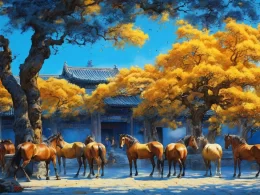

Second Stanza: "叶上初阳干宿雨,水面清圆,一一风荷举。"

Yè shàng chū yáng gān sù yǔ, shuǐ miàn qīng yuán, yī yī fēng hé jǔ.

First sunlight dries last night's rain

on lotus leaves; the pond's surface,

clear and round, lifts wind-stirred blooms

one by one.

Here Zhou's observational genius shines. The precision of "dries last night's rain" (干宿雨) captures a transient moment where night's residue yields to diurnal clarity. "Clear and round" (清圆) describes both water's optical perfection and lotus pads' geometric purity, while "lifts wind-stirred blooms" (风荷举) animates the scene with botanical choreography—each flower a dancer responding to atmospheric cadence. This stanza epitomizes the Song dynasty's gewu (格物) tradition: scrutinizing nature to apprehend cosmic principles.

Third Stanza: "故乡遥,何日去?家住吴门,久作长安旅。"

Gù xiāng yáo, hé rì qù? Jiā zhù Wú mén, jiǔ zuò Cháng ān lǚ.

Homeland so distant—

when will I return?

My house waits at Wu's gate,

while I linger in Chang'an's exile.

The pivot from scenery to sentiment lays bare Zhou's dislocation. "Wu's gate" (吴门) and "Chang'an" (长安) operate as cultural synecdoche—the former representing Jiangnan's watery landscapes, the latter symbolizing bureaucratic entrapment. The juxtaposition underscores the poet's bifurcated identity: a southerner mentally inhabiting lotus ponds while physically confined to northern administrative routines.

Fourth Stanza: "五月渔郎相忆否?小楫轻舟,梦入芙蓉浦。"

Wǔ yuè yú láng xiāng yì fǒu? Xiǎo jí qīng zhōu, mèng rù fú róng pǔ.

Does the fishing lad recall me now,

this fifth month?

In dreams my slender oar

parts the lotus marsh.

The concluding stanza channels homesickness through inverted perspective and oneiric travel. Rather than asserting "I miss home," Zhou questions whether hometown retainers remember him—a rhetorical strategy amplifying emotional vulnerability. The dream sequence ("slender oar parts the lotus marsh") performs psychological homecoming, where "lotus marsh" (芙蓉浦) becomes the ultimate Jiangnan symbol: a floral sanctuary inaccessible in waking life but sovereign in sleep.

Holistic Appreciation

This ci constructs a spatial and temporal palimpsest. The first two stanzas root the poem in Bianjing's material present (incense, sparrows, lotus pond), while the latter two superimpose Jiangnan's remembered and imagined geographies. Zhou's genius lies in making these layers permeable: northern lotus observation triggers southern aquatic nostalgia; capital inertia fuels deltaic dreamscapes.

The poem's structural brilliance manifests in its recursive motifs. Aloeswood smoke (燎沉香) finds its counterpart in dream-marsh mist; sparrows' "peeping beneath eaves" (窥檐语) mirrors the poet's own longing to peer into distant Wu; the "wind-stirred blooms" (风荷举) prefigure the oar-disturbed lotuses of reverie. This mirroring suggests that true poetry resides not in describing scenes but in revealing their hidden resonances across time and space.

Artistic Merits

- Meteorological lyricism:

Weather systems—summer humidity, dawn's clearing, dried rain—become emotional barometers for the poet's inner climate. - Botanical precision:

The lotus description achieves scientific accuracy ("clear and round" leaves) while transcending into metaphor (blooms as uplifted hopes). - Oniric geography:

The dream sequence collapses thousands of li, proving imagination's power over political geography. - Pronominal ambiguity:

"Does the fishing lad recall me?" (渔郎相忆否) leaves the remembered figure tantalizingly vague—childhood friend, alter ego, or literary construct?

Insights

Zhou's poem illuminates how displacement fuels art. His Bianjing lotuses are not mere plants but psychopomps—guides transporting consciousness across physical barriers. The work suggests that homesickness, when distilled through artistic discipline, becomes not just lament but generative force, capable of dreamt homecomings that defy cartographic constraints.

For modern readers navigating fragmented identities, the ci offers a model for mental mobility. Just as Zhou's "slender oar" (小楫) navigates dream marshes, we might cultivate inner vessels to traverse dislocation's waters. The poem ultimately celebrates imagination's sovereignty—proving that while bureaucracies may confine bodies, they cannot chain the dreaming mind's southward voyages.

By framing nostalgia as an active, creative process ("dream enters lotus marsh" 梦入芙蓉浦), Zhou transforms passive longing into artistic agency. His lotuses, rooted in northern ponds yet flowering in southern dreams, symbolize the poet's own existence: physically anchored in capital duties but spiritually flowering in Jiangnan's remembered waters.

About the Poet

Zhou Bangyan (周邦彦 1056 - 1121), a native of Qiantang (modern Hangzhou, Zhejiang), was the culminating master of the wanyue (graceful and restrained) ci poetry of the Northern Song Dynasty. A virtuoso in musical temperament, his ci are renowned for their opulent refinement and technical perfection. He created dozens of new melodic patterns (cipai) and adhered to strict tonal rules, earning him the title "Crown of Ci Poets." His influence extended to Southern Song masters like Jiang Kui and Wu Wenying, establishing him as the founding patriarch of the Rhymed Ci School.