Bows and swords march beyond Elm Pass,

Ink and books climb Penglai’s peak.

Gain comes effortless as loss—

Both are but a passing whim.

Not all ancients were so wise,

Nor are moderns all astray—

Worldly affairs are but a monkey’s game.

This old man cares not for distinctions—

Between inner, outer, or in-between.

Drink when there’s wine,

Write when verse calls,

But never pluck the sword’s lament.

Life is for joy—

Why hasten the greying of hair?

Prosperity brings banners and gold armor,

Poverty means a lame donkey and torn hat—

See them not as opposites.

Such is the way of the world—

Owls and phoenixes will be known in time.

Original Poem

「水调歌头 · 弓剑出榆塞」

弓剑出榆塞,铅椠上蓬山。

得之浑不费力,失亦匹如闲。

未必古人皆是,未必今人俱错,世事沐猴冠。

老子不分别,内外与中间。酒须饮,诗可作,铗休弹。

刘过

人生行乐,何自催得鬓毛斑。

达则牙旗金甲,穷则蹇驴破帽,莫作两般看。

世事只如此,自有识鴞鸾。

Interpretation

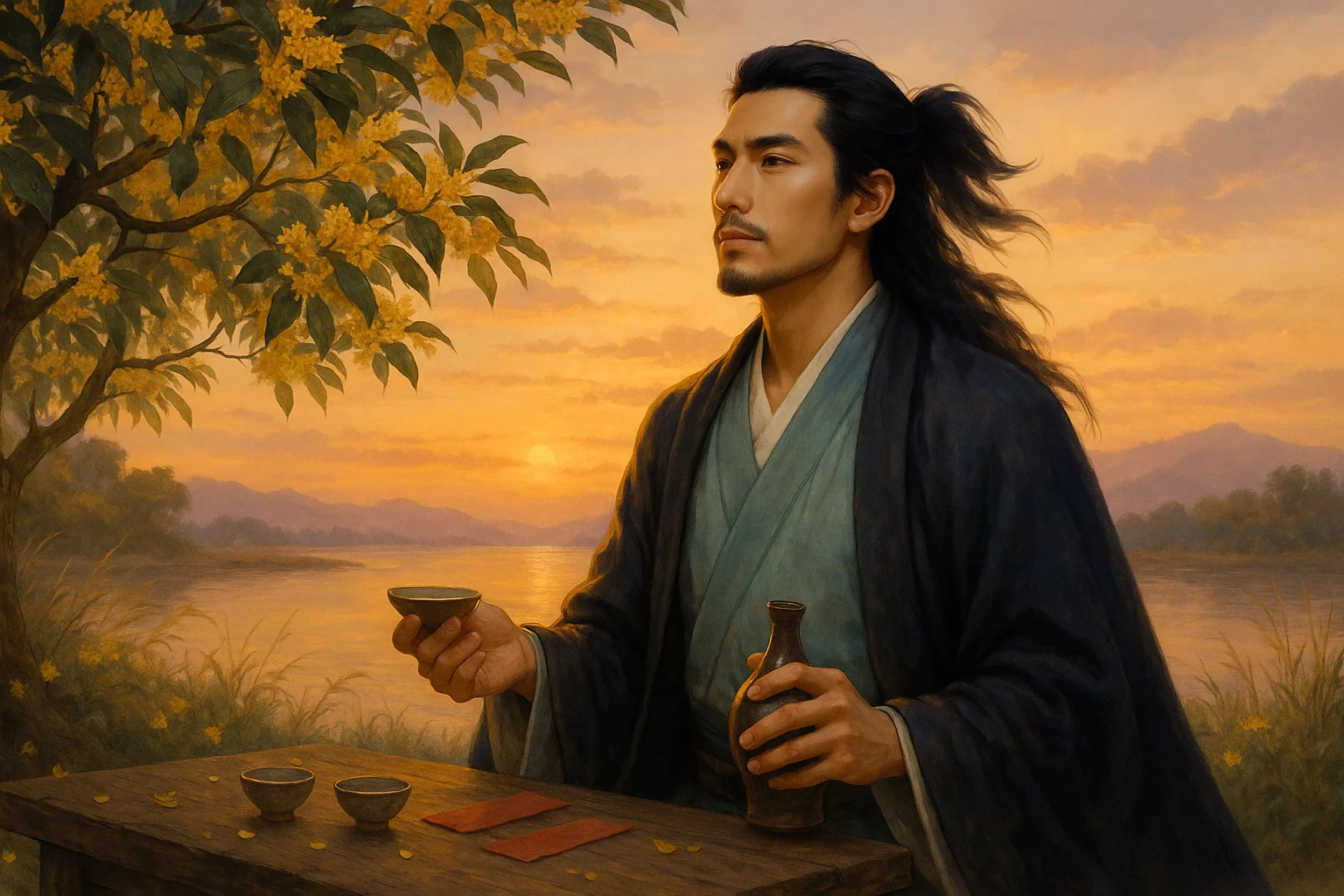

Composed in Liu Guo's later years during the Southern Song's political conservatism, this ci emerges from the intensifying conflict between war and peace factions, with pacifists firmly controlling court politics and repeatedly thwarting advocates for northern campaigns. Though never holding official position, Liu's unfulfilled ambitions and patriotic fervor simmer beneath the surface, channeled into this work that combines seemingly detached reflections on the illusory nature of fame with penetrating critiques of oppressive reality—forming his most authentic spiritual portrait in his twilight years.

First Stanza: "弓剑出榆塞,铅椠上蓬山。得之浑不费力,失亦匹如闲。未必古人皆是,未必今人俱错,世事沐猴冠。老子不分别,内外与中间。"

Gōng jiàn chū yú sài, qiān qiàn shàng péng shān. Dé zhī hún bù fèi lì, shī yì pǐ rú xián. Wèi bì gǔ rén jiē shì, wèi bì jīn rén jù cuò, shì shì mù hóu guān. Lǎo zi bù fēn bié, nèi wài yǔ zhōng jiān.

With bow and sword I marched to Yumen Pass frontier,

With brush and ink I sought Penglai's immortal heights—

What came, came effortlessly without strain,

What went, went as casually as idle pastime.

Not all ancients were invariably right,

Not all contemporaries are wholly wrong—

Worldly affairs are but monkeys wearing official crowns.

This old man distinguishes no more

Between inner circles, outer realms, or in-between.

The first stanza meticulously recounts the poet's life pursuits and tribulations. Liu proclaims his dual cultivation of both martial and literary arts: "bow and sword at Yumen Pass" (弓剑出榆塞) manifests his determination to serve the nation militarily, while "brush and ink toward Penglai" (铅椠上蓬山) demonstrates his scholarly ambition to achieve immortality through writing. This parallel of ideals epitomizes the traditional Confucian scholar's dual aspirations.

However, the seemingly carefree declaration—"gained without effort, lost without care" (得之不费力,失亦匹如闲)—actually conceals profound anguish over unrealized ambitions. Behind Liu's proud demeanor and self-assured talent lies repeated frustration, forcing him to mask his indignation with apparent indifference.

The subsequent lines shift to piercing social commentary. "Not all ancients were invariably right, not all contemporaries wholly wrong" (未必古人皆是,未必今人俱错) reveals his rejection of blind worship of antiquity and advocacy for rational discernment. The caustic metaphor "monkeys wearing official hats" (世事沐猴冠) delivers a scathing indictment of those who pursue fame and profit while lacking substantive ability—mere pretenders occupying positions of power.

When Liu arrogantly refers to himself as "this old man" (老子) claiming to "make no distinctions" (不分别), this feigned detachment from "inner and outer circles" (内外与中间) doesn't signify genuine transcendence, but rather bitter resentment and contempt born from profound disillusionment with the corrupt political landscape.

Second Stanza: "酒须饮,诗可作,铗休弹。人生行乐,何自催得鬓毛斑。达则牙旗金甲,穷则蹇驴破帽,莫作两般看。世事只如此,自有识鸾鴞。"

Jiǔ xū yǐn, shī kě zuò, jiá xiū tán. Rén shēng xíng lè, hé zì cuī dé bìn máo bān. Dá zé yá qí jīn jiǎ, qióng zé jiǎn lǘ pò mào, mò zuò liǎng bān kàn. Shì shì zhǐ rú cǐ, zì yǒu shí luán xiāo.

Drink when wine is present,

Compose poems when inspiration strikes—

No more strumming the sword hilt seeking office.

Why let life's pleasures hasten

The whitening of your temples?

Success brings

Commander's banners and gilded armor;

Poverty means

A lame donkey and tattered hat—

Judge them not as different.

Such is the inevitable way of the world:

True phoenixes among common owls

Will ultimately be recognized.

The second stanza's emotional tone becomes more direct, transitioning to Liu's lamentations and self-exhortations regarding reality. The opening triad—"Drink when wine is present, compose poems when inspired, no more sword-hilt strumming" (酒须饮,诗可作,铗休弹)—delivers a crisp, decisive declaration to abandon political dreams (the "sword-hilt"典故 alluding to Feng Xuan's protest). While ostensibly advocating poetic and alcoholic consolation, this renunciation ("no more strumming") doesn't signify absolute surrender, but rather a reluctant resignation to current political hopelessness.

"Why let life's pleasures hasten the graying of temples?" (人生行乐,何自催得鬓毛斑) carries profound self-reproach. Here Liu interrogates his younger self—why had he wasted prime years obsessing over unattainable official recognition, exhausting his vigor in futile pursuits? This introspection sharpens the stanza's emotional edge.

The subsequent parallel structure—"Success brings commander's banners and gilded armor; poverty means a lame donkey and tattered hat" (达则牙旗金甲,穷则蹇驴破帽)—articulates his philosophy toward life's vicissitudes. The injunction to "judge them not as different" (莫作两般看) transcends mere self-comfort; it's a manifesto asserting moral constancy regardless of circumstance, defending the dignity of the unacknowledged talent.

The culminating line—"Such is the world's way: true phoenixes will be distinguished from owls" (世事只如此,自有识鸾鴞)—resonates with prophetic force. The mythical luan (鸾 phoenix) symbolizes unrecognized genius (Liu's self-image), while the xiāo (鴞 owl) represents vulgar mediocrity. This avian metaphor masterfully transforms the poem's emotional trajectory—from initial fury through introspection and apparent detachment, finally ascending to an undimmable hope. The closing note doesn't negate the preceding anguish, but rather, like embers glowing in darkness, preserves one stubborn spark of conviction that true worth will ultimately be recognized.

Holistic Appreciation

This ci presents a facade of carefree nonchalance and playful detachment from worldly affairs, yet in truth, it is a profound lamentation of the poet's lifelong experience of unrecognized talent and thwarted ambitions. The first stanza speaks of abandoning both literary fame and martial achievements, while the second treats prosperity and adversity with equanimity. Throughout, the poet delivers a trenchant critique of contemporary politics while steadfastly upholding his ideal of personal integrity.

Structurally, though divided into two stanzas, the emotional trajectory progresses continuously—from mocking the world and lamenting the times, through indignation and resentment, to transcendence, self-encouragement, and rekindled hope. The language is unadorned and vigorous, the rhythm bold and impassioned, embodying an aesthetic power that is both "somber and stirring." Particularly striking is the concluding line: after seemingly debasing everything to dust, it suddenly soars, highlighting the poet's unshaken confidence in his own worth despite adversity. This structural reversal from "low to high" is emblematic of the Xin Qiji school's distinctive style.

Artistic Features

- Profound Depth Beneath a Rakish Exterior

Outwardly marked by jesting irreverence and seemingly carefree optimism, the poem actually conceals suppressed emotions—deep sorrow and indignant fury—creating powerful ironic tension. - Masterful Use of Allusions, Ancient Made Personal

References like "plucking the sword-hilt" (弹铗), "command banners and golden armor" (牙旗金甲), and "recognizing phoenixes from owls" (识鸾鴞) are employed naturally yet meaningfully, borrowing ancient forms to express contemporary aspirations. - Dynamic Structural Arrangement

The poetic meaning evolves from exuberance to solemnity, from solemnity to tranquility, and from tranquility to exultation, with emotion and rhythm advancing in tandem, forming an unbroken flow. - Unvarnished Emotion, Straight from the Heart

The language is unpolished, unfettered by strict prosody, pouring forth directly from the poet's impassioned heart, brimming with感染力 and authenticity.

Insights

Liu Guo's ci is not merely a lament over personal misfortune but an attitude of disillusionment without loss of idealism toward his era. Rather than succumbing entirely to indignation, he transforms sorrow into resolve through irony and asserts his convictions by satirizing the world. The vicissitudes of life should not negate self-worth; distinctions between high officials and impoverished commoners should not define human value. Through pages of grievances, he gives voice to a soul both flesh-and-blood and luminous with indignation—one that reflects the darkness of the Southern Song's chaotic age while still shining with undimmed ideals.

Today, this "outwardly wild, inwardly tormented" state of being remains worthy of contemplation. To maintain faith and self-respect amid injustice, to criticize the world without sycophancy, to voice discontent without vulgarity—this is Liu Guo's legacy: one may be angry, one may speak boldly, but one must never lose one's resolve.

About the Poet

Liu Guo (刘过 1154 - 1206), a native of Taihe in Jiangxi, was a ci poet of the Bold and Unconstrained School (haofang pai) during the Southern Song Dynasty. Though he remained a commoner all his life, wandering the rivers and lakes, he associated with literary giants like Lu You and Xin Qiji. His ci poetry is impassioned and heroic, and his verse is vigorous and forceful. Stylistically close to Xin Qiji but even more unrestrained, Liu Guo became a central figure among Xin’s poetic followers.