The sheep and cattle come to rest,

All thatched gates closed east and west.

The gentle breeze and the moon bright

Remind me of homeland at night.

Among rocks flow fountains unseen;

Autumn drips dewdrops on grass green.

The candle brightens white-haired head.

Why should its flame blaze up so red?

Original Poem

「日暮」

杜甫

牛羊下来久,各已闭柴门。

风月自清夜,江山非故园。

石泉流暗壁,草露滴秋根。

头白灯明里,何须花烬繁。

Interpretation

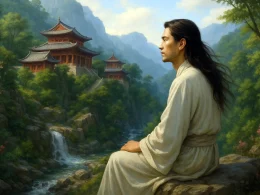

This poem was composed in the autumn of 767 CE, the second year of the Dali era under Emperor Daizong. Du Fu was then residing in Rangxi, Dongtun, Kuizhou (present-day Fengjie, Chongqing). Although the An Lushan Rebellion had been quelled, separatist warlords held power, Tibetan incursions continued, and the nation remained unstable. The poet, fifty-six years old, saw no way to return north, struggled for livelihood, and was afflicted by lung disease and rheumatism. Written on an ordinary autumn dusk, the poem appears on the surface as a sketch of a mountain village scene but is, at its core, a crystallization of Du Fu's profound contemplation in his later years on life's final harbor and his spiritual homeland.

First Couplet: “牛羊下来久,各已闭柴门。”

Niú yáng xiàlái jiǔ, gè yǐ bì cháimén.

The sheep and oxen came down the slopes long ago; / At every house, the wooden gates are closed.

The opening resembles an ink-wash painting of a mountain dwelling at dusk, serene and full of life. The word "long ago" is subtle, indicating both the deepening twilight and the completion of the homeward journey, while also hinting at the poet's own prolonged gazing and lingering. While all things have found their rest—the herds to their pens, people to their homes—the poet alone remains an "observer" outside this peaceful scene. The closed "wooden gates" physically demarcate inside from outside and symbolically represent his estrangement from this land and this moment in time.

Second Couplet: “风月自清夜,江山非故园。”

Fēngyuè zì qīng yè, jiāngshān fēi gùyuán.

The breeze and moon make their own lovely, lucid night; / These rivers and hills are not my homeland.

This couplet is the pivotal point of the poem's emotion and a manifestation of Du Fu's philosophical depth. "The breeze and moon make their own lovely, lucid night" describes the self-sufficient beauty of nature, which remains clear and bright regardless of human feelings. "These rivers and hills are not my homeland" articulates the eternal human longing for home and the crisis of belonging. The word "make their own" highlights the tension between nature's self-contained ease and man's self-inflicted sorrow. The word "not" is resolute, pushing all the splendid scenery into the distance as the landscape of an "other." The lovelier the clear night, the sharper the longing for home; the grander the rivers and hills, the deeper the sense of displacement.

Third Couplet: “石泉流暗壁,草露滴秋根。”

Shí quán liú àn bì, cǎo lù dī qiū gēn.

Over darkened cliffs the stony springs flow on; / On autumn roots, the meadow dewdrops fall.

The focus shifts from distant observation to close listening, from the visual to the auditory and tactile. "Flow on over darkened cliffs" and "fall on autumn roots" capture the subtle, often-ignored sounds of the microcosmic world. Springs flowing in shadowed places, dew condensing on grass roots—these fine, obscure, cool images mirror the silent flow of sorrow and the privately congealed loneliness deep within the poet's heart. The chill of the autumn night and the sense of time's passage are conveyed directly through the minute action of "fall." Not a single word here expresses emotion, yet deep feeling resonates throughout.

Fourth Couplet: “头白灯明里,何须花烬繁。”

Tóu bái dēng míng lǐ, hé xū huā jìn fán.

White-haired within the lamplight's lonely glow— / Why should the lampwick's glowing blossoms flourish so?

The scene shifts completely from the outdoors to the interior, focusing finally from space onto the soul itself. "White-haired" is a direct portrayal of life's twilight; "the lamplight's lonely glow" is the sole source of light and companionship in this twilight. A profuse snuff (the "glowing blossoms" at the lampwick's end) was commonly considered an auspicious omen. Yet the poet's rhetorical "why should" expresses his alienation and weariness toward such illusory "good omens" from fate. The essence of life has been spent like the lamp's oil; external signs of "flourishing" have lost their meaning. This single question lays bare the profound contradiction between prosperity and extinction, hope and disillusionment. It is profoundly mournful, yet utterly clear-eyed.

Holistic Appreciation

This poem is a masterpiece of Du Fu's late-period regulated verse, showcasing his artistic maturity in turning from grand historical narratives toward the exploration of the inner cosmos. The poem unfolds like a slowly advancing camera shot: from a long shot (the mountain village at dusk) → to a medium shot (the moonlit rivers and hills) → to a close-up (the stony springs and meadow dew) → to an extreme close-up (the white hair in lamplight). Space contracts layer by layer, finally focusing on the poet's own contemplation of existence.

The poem's core tension lies in the contrast between "nature's eternal order" and "human life's transience and rootlessness." The herds have their pens, the people their doors, the breeze and moon their constancy, the springs and dew their season—all things exist within some order or cycle. Only the poet, hair already white, knows not where he belongs; life approaching its evening, he sees no true "homeland." This sense of "disorder" and "lack of return" makes him, at the hour when all things rest, the most profoundly "conscious solitary."

The poem's emotion is deeply restrained—sorrowful but not despairing, plaintive but not indignant. Beneath the desolation lies an understanding and acceptance of fate born of a weathered life, and the resilient poetry of retaining the ability to perceive the beauty of the "lucid night" even after acknowledging "these rivers and hills are not my homeland."

Artistic Merits

- Portraying Inner Psychological Time through Stillness: Words like "long ago," "make their own," "flow on," and "fall" suggest a slow, continuous, almost stagnant sense of time. This aligns with the poet's late-life experience of wandering and monotonous days, where the passage of physical time intertwines with the stagnation of psychological time.

- An Aesthetic of Solitude in Imagery: Images like "closed wooden gates," "darkened cliffs," "autumn roots," and "white-haired within the lamplight" all carry qualities of enclosure, obscurity, aging, and isolation. Together they construct an aesthetic space stripped of splendor, confronting the authentic state of life, reflecting the "tranquil" aspect within Du Fu's late style of "deep poignancy and tightly controlled rhythm."

- The Power of Transitional Words: The turn created by "make their own" versus "not," and the rhetorical challenge of "why should," generate emotional ripples and intellectual steepness within the calm narration. These words are the crucial valves through which the poet's subjective feeling intervenes in the objective scene—concise and powerful.

- Paradox and Transcendence in the Closing Couplet: The final couplet juxtaposes "white-haired" (decay) with "glowing blossoms flourish" (vitality), creating a paradox of life. The poet's "why should" is not numbness, but rather, after seeing through life's appearances, a steadfast holding to an inner spiritual harbor and a rejection of illusory external adornment. It possesses a tragic nobility.

Insights

This work teaches us that life's profundity may come not from glorious achievements but from moments of clarity and honest articulation regarding one's own existential situation, often found in ordinary, even solitary, hours. Within the everyday scene of "the sheep and oxen came down the slopes long ago," Du Fu saw his own estrangement from the order of all things. Before the constant beauty of "the breeze and moon make their own lovely, lucid night," he recognized the eternal homesickness of "these rivers and hills are not my homeland."

This poem speaks to the "spiritual displacement" every modern person may face. Do we not also often feel like strangers amidst prosperity? Are we also seeking a "homeland" that may not exist geographically? Du Fu's answer is: to acknowledge this loneliness and estrangement, and within this clarity, to still listen to the subtle music of "stony springs flow on over darkened cliffs," and to guard that point of one's own, true light within "the lamplight's lonely glow." The true homecoming may precisely be this courage itself—to preserve perception while displaced, to persist in articulation while alone.

Poem translator

Xu Yuanchong (许渊冲)

About the poet

Du Fu (杜甫), 712 - 770 AD, was a great poet of the Tang Dynasty, known as the "Sage of Poetry". Born into a declining bureaucratic family, Du Fu had a rough life, and his turbulent and dislocated life made him keenly aware of the plight of the masses. Therefore, his poems were always closely related to the current affairs, reflecting the social life of that era in a more comprehensive way, with profound thoughts and a broad realm. In his poetic art, he was able to combine many styles, forming a unique style of "profound and thick", and becoming a great realist poet in the history of China.