The young prince shines with talent bright,

Drunk with joy on heights, he forgets night.

Songs fade as coral trees are admired,

Deep affection fills amber cups fired.

May he live a thousand years in cheer,

Golden chrysanthemums bloom each autumn clear.

Original Poem

「抛球乐 · 年少王孙有俊才」

冯延巳

年少王孙有俊才,登高欢醉夜忘回。

歌阑赏尽珊瑚树,情厚重斟琥珀杯。

但愿千千岁,金菊年年秋解开。

Interpretation

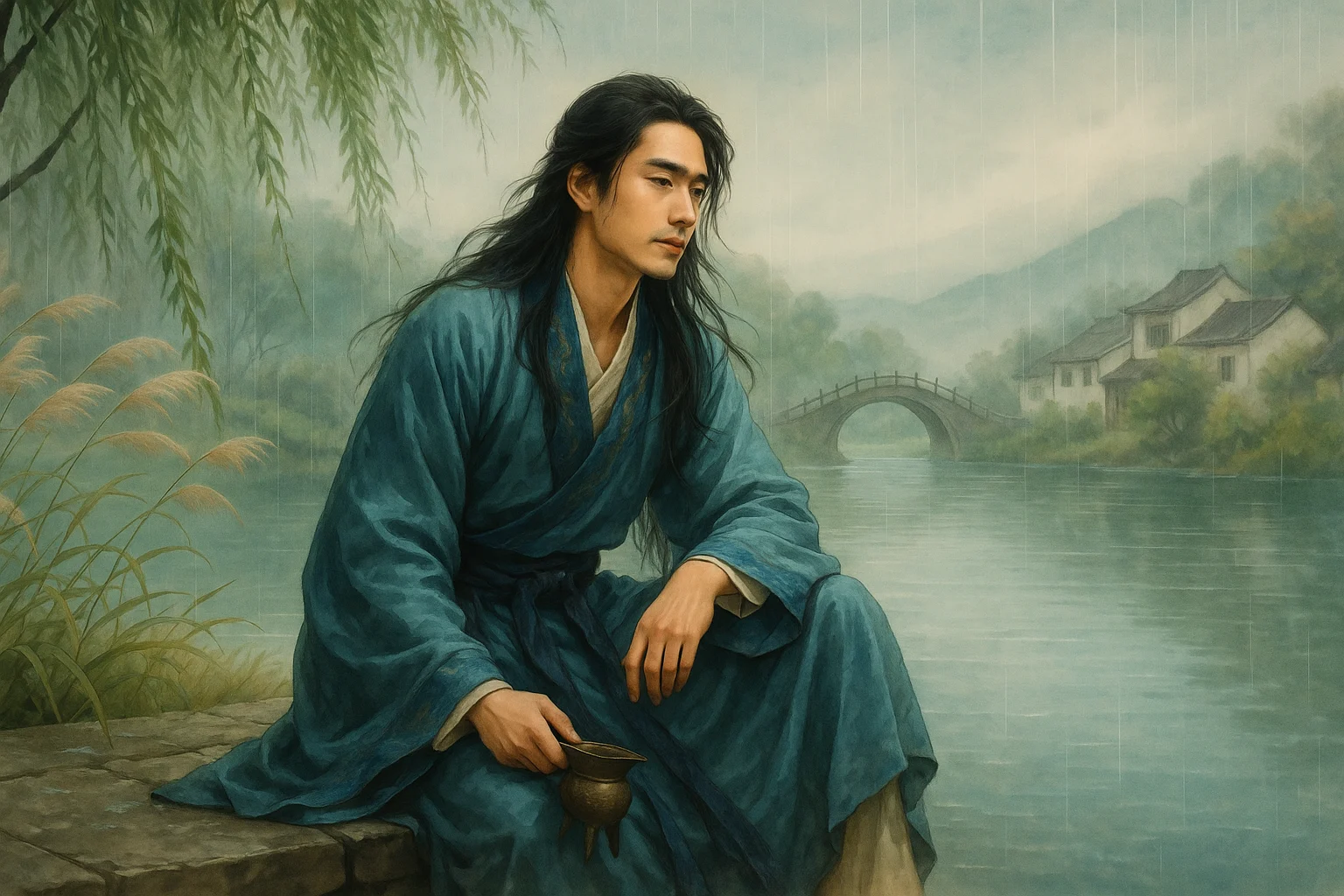

Composed during the Baoda era (943-957) of Southern Tang, this ci captures the zenith of Feng Yansi's political and literary career—a period when he served three terms as chancellor amidst Nanjing's glittering aristocratic circles. The poem immortalizes a lavish nocturnal banquet, where "ascending heights," "amber cups," and "coral trees" transcend material opulence to become vessels for profound meditations on human connection. Feng's signature fusion of splendor and sentiment finds perfect expression in this celebration of camaraderie and the aristocratic ethos.

First Stanza: "年少王孙有俊才,登高欢醉夜忘回。"

Nián shào wáng sūn yǒu jùn cái, dēng gāo huān zuì yè wàng huí.

The young prince, brimming with genius,

ascends heights—drunk on joy, forgetting night's return.

The opening couplet paints the banquet's host as the epitome of Southern Tang's cultivated aristocracy. "Ascends heights" (登高) operates on dual planes: literally mounting a terrace for revelry, metaphorically embodying intellectual and spiritual elevation. "Forgetting night's return" (夜忘回) crystallizes the revelers' Dionysian abandon—time suspended in amber-lit euphoria.

"歌阑赏尽珊瑚树,情厚重斟琥珀杯。"

Gē lán shǎng jìn shān hú shù, qíng hòu zhòng zhēn hǔ pò bēi.

Songs fade as coral treasures are admired to satiety,

affection weighs heavy—amber cups refilled anew.

The stanza's pivot from auditory ("songs fade") to visual ("coral treasures") mirrors the banquet's sensory progression. "Coral trees" (珊瑚树), exotic maritime luxuries displayed as conversation pieces, epitomize Southern Tang's cosmopolitan wealth. The "heavy" affection (情厚) materializes through the ritual of cup-refilling—each pour a liquid promise of enduring fellowship.

Second Stanza: "但愿千千岁,金菊年年秋解开。"

Dàn yuàn qiān qiān suì, jīn jú nián nián qiū jiě kāi.

"May we toast a thousand thousand years—

golden chrysanthemums blooming perennially in autumn!"

The closing couplet elevates the revelry into timeless invocation. "Thousand thousand years" (千千岁) echoes royal birthday toasts, here democratized for shared immortality. "Golden chrysanthemums" (金菊), blooming defiantly in autumn's decline, become emblems of friendship's resilience—possibly nodding to the Double Ninth Festival's tradition of chrysanthemum-viewing banquets. The final image lingers like wine's afterglow: seasonal flowers transformed into eternal vows.

Holistic Appreciation

Though concise in form, this short ci flows with an unbroken vitality, unfolding in layers to depict the opulence of a Southern Tang noble banquet while delving into emotional depth. The poet begins by portraying the host’s brilliant talent, transitions into scene-setting and object symbolism, then culminates in heartfelt wishes—a complete structure brimming with emotion.

Linguistically, the poem blends elegance and naturalism. Phrases like "dashing genius" and "joyous intoxication" exude spirited charm, while lavish imagery such as "coral trees" and "amber cups" evokes grandeur without descending into gaudiness. Instead, the poet’s masterful pacing and emotional progression infuse the banquet scene with scholarly reflection and aristocratic ethos.

Moreover, lines like "pouring with deep affection" and "golden chrysanthemums bloom yearly" transcend mere feasting descriptions, expressing reverence for friendship and cherished moments. It is perhaps this sincerity that has earned the poem enduring acclaim across generations.

Artistic Merits

- Opulent Imagery

Symbols like "coral trees" and "amber cups" not only depict luxury but also embody aristocratic life, enriching the poem’s allegorical texture. - Structural Progression: Human-Scene-Object-Emotion

The poem moves seamlessly from character sketches to environmental details, then to material opulence, finally ascending to emotional climax—a clear, layered architecture. - Banquet as Lyrical Expression

The depicted feast is not just a material tableau but an externalization of camaraderie, sentiment, and intellectual pursuit. - Lively Rhythmic Language

Short, brisk lines and vivid, compact imagery create an oral musicality and singable quality. - Toast-Style Conclusion

The closing benediction ("May it last a thousand years") implies unspoken feelings, embodying an art where "poetry holds wine, and wine reveals sentiment."

Insights

Though this work by Feng Yansi celebrates banquet pleasures and aristocratic joys, beneath its surface of revelry lies profound meditation on youth, friendship, and life’s fleeting moments. Descriptions of "youthful genius" and "drunken heights" are not mere praise for human brilliance but implicit reflections on cherishing life’s zenith. The closing wish—"golden chrysanthemums blooming yearly in autumn"—transmits a universal longing for beauty beyond time’s erosion.

Amid life’s peaks, it is meaningful to love, share, and sing unrestrainedly. Yet more precious is sustaining genuine bonds and treasuring deep human connections behind the glamour. When feasts disperse and lights dim, those warm toasts and heartfelt blessings become the eternal keepsakes of the heart. Furthermore, the poet’s exquisite language and rhythm transform luxury into art, reminding us that between material and spiritual pursuits, harmony can be found through poetry and aesthetic grace. This alchemical ability to sublimate the worldly into art is why literati poets still resonate across millennia.

About the Poet

Feng Yansi (冯延巳 903 - 960), courtesy name Zhengzhong, was a native of Guangling (modern-day Yangzhou, Jiangsu) and a renowned ci poet of the Southern Tang during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. Rising to the position of Left Vice Director of the Department of State Affairs (Zuo Puye Tongping Zhangshi), he enjoyed the deep trust of Emperor Li Jing. His ci poetry forged a new path beyond the Huajian tradition, directly influencing later masters like Yan Shu and Ouyang Xiu, playing a pivotal role in the transition of ci from "entertainment for musicians" to "literary expression of scholar-officials."