It's rainy day after day on riverside;

How bleak is autumn in this southern land!

High winds blow down leaves from trees far and wide;

I put on my fur robe in night long and grand.

I look oft in the mirror for achievements vain;

I lean alone on rails, free to go or to stay.

In dangerous times I long to serve my sovereign;

Though old and weak, I cannot but do my way.

Original Poem

「江上」

杜甫

江上日多雨,萧萧荆楚秋。

高风下木叶,永夜揽貂裘。

勋业频看镜,行藏独倚楼。

时危思报主,衰谢不能休。

Interpretation

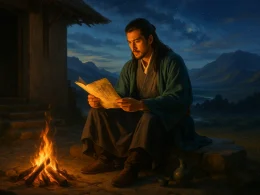

This work was composed in the late autumn of 769 CE, during the fourth year of the Dali era under Emperor Daizong. It stands as a spiritual portrait from the final three years of Du Fu’s life, a period of relentless wandering. At this time, the poet was adrift in the Jing‑Chu region (present‑day Hubei and Hunan). Although the An Lushan Rebellion had been quelled, the Tang Empire was in an irreversible decline, beset by separatist warlords, Tibetan incursions, and a corrupt court. At fifty‑eight, Du Fu was impoverished, ill, and without hope of returning north, yet his fervent concern for the nation and his desire to serve his sovereign remained undimmed. This poem was born precisely from the acute conflict between his physically depleted state and his spiritually unyielding resolve—a poignant “spiritual autobiography of an aged and unwavering patriot.”

First Couplet: “江上日多雨,萧萧荆楚秋。”

Jiāng shàng rì duō yǔ, xiāoxiāo Jīng Chǔ qiū.

Day after day, rain falls on the river; / Desolate, the autumn of Jing and Chu.

The opening unfolds like a wide‑angle lens capturing time and space. “On the river” situates his wandering condition. “Day after day, rain” is not merely descriptive; the persistently gloomy weather mirrors the murkiness of the era and his own state of mind. “Desolate” is quintessential Du Fu—a synesthetic auditory image, the sound of the autumn wind sweeping the land, also the lament of all things withering under history’s wheel. The three words “autumn of Jing and Chu” embed his personal plight deeply into a landscape steeped in historical sorrow (where Qu Yuan was exiled) and geographical vastness, establishing the poem’s somber, desolate tone.

Second Couplet: “高风下木叶,永夜揽貂裘。”

Gāo fēng xià mù yè, yǒng yè lǎn diāoqiú.

A fierce wind brings down ten thousand leaves; / Through the endless night, I clutch my worn fur robe.

The gaze draws inward from the wilderness to his immediate surroundings, the imagery growing more stark and poignant. “A fierce wind brings down ten thousand leaves” is both the actual scene before him and a symbol of worthy talents falling and civilization decaying amidst the era’s great upheaval. “Through the endless night, I clutch my worn fur robe” turns from the external to the internal, conveying the physical chill of an aging body and the spiritual loneliness of a rootless soul. “Endless night” hints at his habitual insomnia and serves as a metaphor for his spirit’s prolonged endurance in a dark age. “Brings down” and “clutch”—one dynamic, one static—sketch the difficult posture of a solitary life striving to hold itself together under the onslaught of ruthless external forces.

Third Couplet: “勋业频看镜,行藏独倚楼。”

Xūn yè pín kàn jìng, xíng cáng dú yǐ lóu.

For deeds still unachieved, I face the mirror time and again; / To act or withdraw, alone I lean on the tower, weighed by thought.

This couplet turns to a deep examination of his inner world, among the most introspective lines in Du Fu’s poetry. “For deeds still unachieved, I face the mirror time and again” contains multiple layers of self‑interrogation: the white hair in the mirror is a stark reminder of life’s passing and a silent challenge to a lifetime of unfulfilled ambition. The word “time and again” reveals the repetition of the action and the depth of his anxiety. “To act or withdraw, alone I lean on the tower, weighed by thought” lays bare the eternal dilemma of the Confucian scholar regarding engagement and retreat. The silhouette of “alone I lean on the tower” speaks of physical solitude, but more profoundly, of the spiritual isolation of bearing fateful choices alone, with no one to counsel him. These two lines exhibit masterful parallelism, seamlessly fusing external gesture with internal reflection.

Fourth Couplet: “时危思报主,衰谢不能休。”

Shí wēi sī bào zhǔ, shuāi xiè bù néng xiū.

As danger grips the age, my thought turns keen to serve my lord; / Though wasted, worn, and weakening, this will cannot be stilled.

From this extreme tension bursts the poem’s strongest declaration, the crystallization of Du Fu’s lifelong spirit. “As danger grips the age” and “wasted, worn, and weakening” are the harsh realities confronting the poet. “My thought turns keen to serve my lord” and “this will cannot be stilled” are the indomitable convictions rising in response. These two pairs of ideas create immense dramatic force: one represents the dual negation by era and body, the other the absolute affirmation of spirit and purpose. Ultimately, the spirit transcends material limits. In the phrase “cannot be stilled,” we see not an old man’s resignation but a patriot’s solemn choice—to oppose despair with a failing body, to answer his time’s call with an individual’s unwavering will.

Holistic Appreciation

This five‑character regulated verse is a paradigm of the perfect unity of Du Fu’s late poetic craft and moral character. It fully embodies the defining quality of his late poetry: “an immensity held within”—where emotion no longer erupts outward but turns inward, condenses, and finally transforms into a steadfast, sorrowful spiritual presence, hard as forged metal.

The poem’s structure follows an implicit progression of “scene—body—mind—will,” a gradual internalization and sublimation: the first two couplets use the desolate autumn scene to reflect the ailing body; the third focuses on inner anxiety and contemplation; the final couplet, amidst all negative circumstances, resolutely asserts an undeniable spiritual sovereignty. This movement from outer to inner, then from a fortified inner core back toward the world, ensures that while the poem speaks of decline, it carries an unyielding, vigorous force.

The unique value of this work lies in its candid revelation of how a great soul harbors both fragility and resilience. The poem acknowledges with clear‑eyed recognition the state of being “wasted, worn, and weakening,” and conveys immense anxiety over the emptiness of “deeds still unachieved.” Yet ultimately, this does not lead to despair or nihilism. Instead, provoked by “danger grip[ping] the age,” it ignites a purer, more absolute sense of moral duty. This is a self‑affirmation forged in extremity.

Artistic Merits

- Tension Between Desolate Imagery and Unbending Spirit: Images like “day after day rain,” “desolate,” “brings down… leaves,” “endless night,” and “wasted, worn, and weakening” all evoke decay and finality. Yet actions and determinations like “face the mirror time and again,” “my thought turns keen to serve my lord,” and “cannot be stilled” reveal an unsubdued vitality. This contrast between imagery and spirit creates the poem’s powerful internal artistic tension.

- Profound Self‑Dialogue Within Parallel Structure: “Deeds still unachieved” parallels “to act or withdraw”; “face the mirror time and again” parallels “alone I lean on the tower.” This is not merely formal parallelism but a substantive self‑questioning and dialectic. The mirror reflects the present self; the heart holds the ideal achievement. Leaning alone on the tower is the solitary self; below lies the uncertain path. Here, parallelism becomes the exquisite external form of an internal struggle.

- The Oppressive Weight of Temporal Imagery: “Day after day rain” (time’s drawn‑out passage), “endless night” (time’s stagnant grip), “time and again” (time’s repetitive press), “wasted, worn, and weakening” (time’s ultimate effect)—together they evoke a powerful anxiety over time’s flow, life’s urgency, and the absence of fulfilled purpose. This is the quintessential temporal experience of Du Fu’s late poetry.

- The Transformative Power of the Final Couplet: After the first three couplets thoroughly establish hardship, aging, and solitude, the final couplet suddenly ascends with “my thought turns keen to serve my lord” and concludes with the resolute stance of “cannot be stilled.” Like lightning cleaving gloom, it reveals the core radiance and fortitude of Du Fu’s spirit.

Insights

This masterpiece poses an eternal question: When an individual’s vital power (“wasted, worn, and weakening”) comes into severe conflict with the moral duty they feel (“as danger grips the age, my thought turns keen to serve my lord”), how should one live? Du Fu’s answer is “cannot be stilled.” This is not blindness to encroaching age, but a conscious choice—made with full awareness of his limitations—to place spiritual will above physical reality, a form of moral heroism.

It teaches us that true commitment often manifests not in fervent proclamation during favorable times, but in the perseverance that continues after recognizing one’s own smallness, powerlessness, and even decay. Du Fu’s greatness lies less in achieving his ambition to stabilize the world and comfort the people, and more in maintaining this original intent to “serve my lord” and this adamantine resolve that “cannot be stilled” when all possibility of fulfillment had nearly vanished.

In our contemporary world, we may no longer operate within the classical framework of “serving my lord,” but this spirit of “cannot be stilled” despite being “wasted, worn, and weakening” remains a vital force against utilitarian calculation and the creep of nihilism. It reminds us that human dignity and worth are often most nobly embodied precisely in the act of persevering when one knows the endeavor may be impossible. Du Fu’s solitary chant on the autumn river of Jing‑Chu ultimately becomes an enduring echo—the echo of conscience and responsibility refusing to yield in any difficult age.

About the poet

Du Fu (杜甫), 712 - 770 AD, was a great poet of the Tang Dynasty, known as the "Sage of Poetry". Born into a declining bureaucratic family, Du Fu had a rough life, and his turbulent and dislocated life made him keenly aware of the plight of the masses. Therefore, his poems were always closely related to the current affairs, reflecting the social life of that era in a more comprehensive way, with profound thoughts and a broad realm. In his poetic art, he was able to combine many styles, forming a unique style of "profound and thick", and becoming a great realist poet in the history of China.