Steel-blue hills stand,

Who dares sound jade-flute o’er war’s water?

The scow ships a banished soul to slaughter!

Reed-arrows fly ’neath moon’s ice-blade,

My march-gaze frayed—

Daybreak’s pass seals where comrades fade.

Original Poem

「归自谣 · 寒山碧」

冯延巳

寒山碧,江上何人吹玉笛?扁舟远送潇湘客。

芦花千里霜月白,伤行色,来朝便是关山隔。

Interpretation

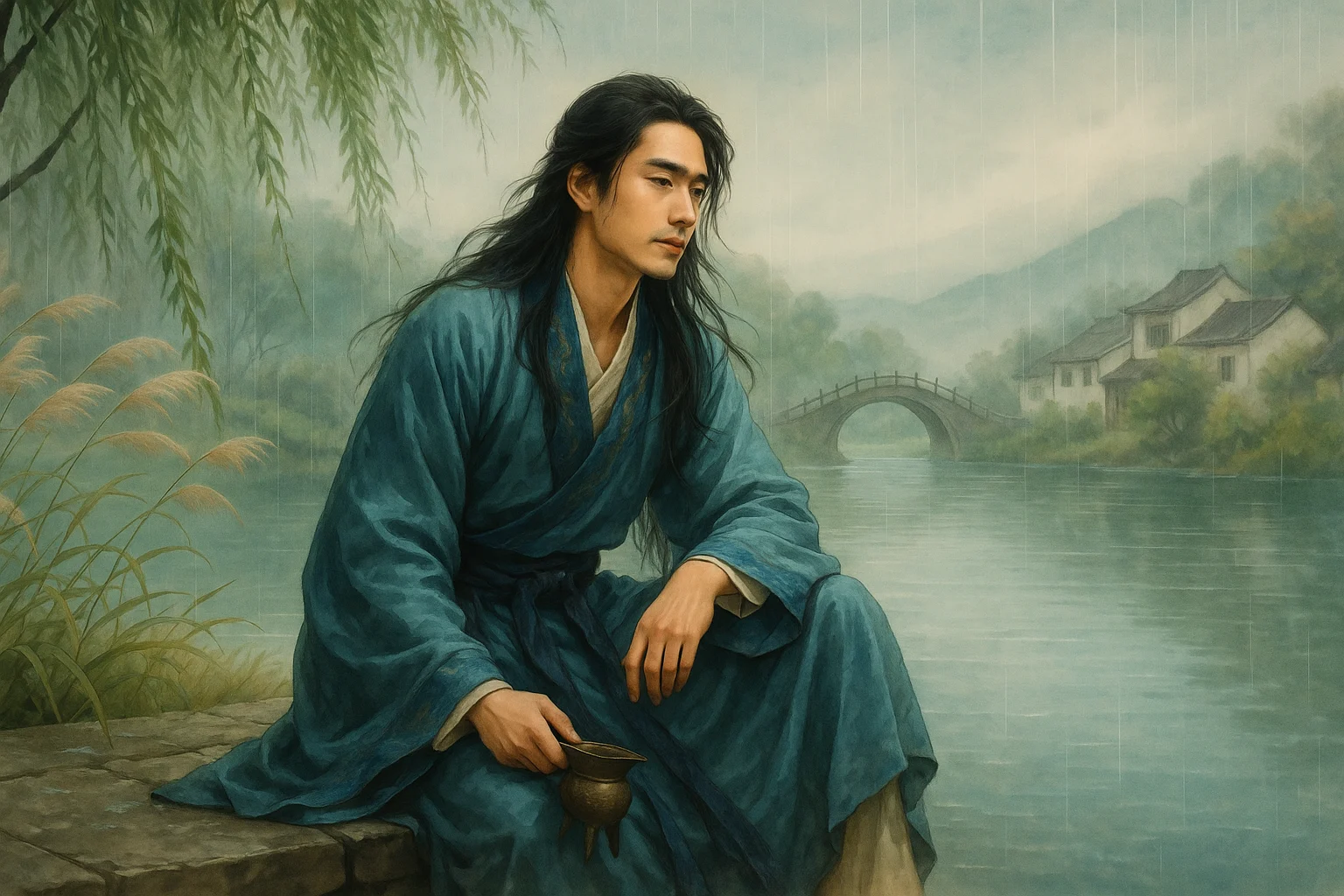

This farewell ci poem, with its expansive imagery and profound sentiment, transcends mere personal separation to explore universal human experience. Through ethereal, desolate landscapes, Feng crafts a vast melancholic atmosphere where parting sorrow merges seamlessly with nature, achieving a rare philosophical depth. The work exemplifies Feng's signature style—"graceful yet poignant, sparse yet nuanced"—and stands as a monumental representative of his "exceptionally broad artistic domain."

First Stanza: "寒山碧,江上何人吹玉笛?扁舟远送潇湘客。"

Hán shān bì, jiāng shàng hé rén chuī yù dí? Piān zhōu yuǎn sòng Xiāo Xiāng kè.

Cold mountains emerald,

who on the river plays this jade flute's mournful note?

A lone boat carries the Xiang wanderer afar.

The opening trinity of words—"cold mountains emerald" (寒山碧)—strikes with masterful economy, instantly transporting readers to autumn's vast riverbanks. This majestic, pristine inception rivals Li Bai's "cold mountains' heartbreaking jade" while surpassing it in spatial grandeur. The subsequent "who plays this jade flute?" introduces an aural layer to the visual tableau, creating a synesthetic landscape where the flute's elusive melody—its player unseen—heightens the night's loneliness. The stanza culminates in the parting act: "a lone boat carries the Xiang wanderer." Though "Xiang wanderer" (潇湘客) nominally refers to the traveler, its evocation of the misty Xiang River region imbues the scene with mythic melancholy, transforming personal farewell into cosmic separation.

Second Stanza: "芦花千里霜月白,伤行色,来朝便是关山隔。"

Lú huā qiān lǐ shuāng yuè bái, shāng xíng sè, míng zhāo biàn shì guān shān gé.

Reed flowers for miles, frost-moon bleached—

this journey's hues grieve me.

At dawn, mountain passes will divide us.

The stanza deepens the fusion of emotion and scenery. "Reed flowers for miles" (芦花千里) paints the riverbank's boundless reeds—a visual metaphor for life's ephemerality—now doubly chastened by "frost-moon's bleaching" (霜月白), where lunar coldness parallels the poet's inner desolation. "This journey's hues grieve me" (伤行色) transcends specific sorrow to lament parting's existential weight. The finale—"mountain passes will divide us" (关山隔)—propels the emotion from present separation to future irrevocability, compressing spatial distance and temporal permanence into one devastating line. The poem's structure, though minimalist, achieves profound psychological and spiritual ascent, concluding with resonant inexhaustibility.

Holistic Appreciation

This poetic work paints a classic "autumn river farewell scene" with cool-toned, minimalist brushstrokes, blending vision, sound, and emotion into a single artistic vision. Its most striking feature is using ethereal imagery to convey profound sentiment without descending into overt melancholy. The poet excels at extracting deeply symbolic motifs from everyday scenery—such as "cold mountains," "jade flute," "reed flowers," and "frost moon"—and through techniques like negative space, rhetorical questions, and the interplay of reality and illusion, he internalizes emotion, writing not just of "sending someone off" but also of the hidden loneliness, sorrow, loss, and resignation behind the farewell.

Structurally compact, the poem unfolds in three layers across six lines: the first depicts what is seen, the second what is heard, and the third what is felt. Scenery carries emotion, and emotion shapes the scene. Though belonging to the lyrical tradition, it avoids fragility, instead achieving a vast, seamless artistic realm—embodying what Wang Guowei called "a grand hall" in artistic ambition. It stands uniquely within the Five Dynasties ci style and even foreshadows the Song dynasty's "theory of artistic conception."

Artistic Merits

- Expansive Imagery

Beginning with "cold mountains, emerald," the poem opens into an ethereal, boundless river-and-sky tableau, never confined to petty sorrow. - Concise, Refined Language

With just a few strokes, it organically fuses scenery, emotion, and time, weaving them together without clutter. - Restrained, Profound Emotion

Though depicting "the sorrow of parting," it avoids excessive dramatization, instead embedding feeling in scenery and meaning in objects. - Clear Structural Layers

The progression from opening to climax is palpable, and the final line delivers a powerful resolution, guiding the poem’s emotional flow naturally.

Insights

This ci teaches us that deep emotion does not require elaborate expression. True literary beauty lies in hearing thunder in silence and glimpsing vastness in simplicity. Feng Yansi uses the setting of an empty autumn night to make us feel the irreversible pain of farewell and the difficulty of reunion in life. His poem reminds us that certain emotions—nostalgia, parting sorrow, loneliness—often defy words, yet through scenery and art, they can reach profound shared understanding. Even when facing farewells across mountains and rivers, if we can, like this ci, elevate finite time and space into boundless sentiment and perspective, then parting too can become tender, profound, and moving.

About the Poet

Feng Yansi (冯延巳 903 - 960), courtesy name Zhengzhong, was a native of Guangling (modern-day Yangzhou, Jiangsu) and a renowned ci poet of the Southern Tang during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. Rising to the position of Left Vice Director of the Department of State Affairs (Zuo Puye Tongping Zhangshi), he enjoyed the deep trust of Emperor Li Jing. His ci poetry forged a new path beyond the Huajian tradition, directly influencing later masters like Yan Shu and Ouyang Xiu, playing a pivotal role in the transition of ci from "entertainment for musicians" to "literary expression of scholar-officials."