Bandits plague our fragile lives with dread;

Taxes strip the foreign poor till bled.

An empty village—only birds take flight;

At sunset, not a soul in fading light.

Through ravines I walk, the wind whips my face;

'Neath pines I watch dew drip with silent grace.

I turn my graying head toward distant peaks;

On battlefields, the yellow dust still speaks.

Original Poem

「东屯北崦」

杜甫

盗贼浮生困,诛求异俗贫。

空村惟见鸟,落日未逢人。

步壑风吹面,看松露滴身。

远山回白首,战地有黄尘。

Interpretation

This work was composed in the autumn of 767 CE, the second year of the Dali era under Emperor Daizong, while Du Fu was residing in the Dongtun area of Kuizhou (present-day Fengjie, Chongqing). The title "Northern Hollow" refers to the northern slopes of the mountainous region. Although the An Lushan Rebellion had been quelled, the land of Shu was still riven by warlord conflicts and plagued by marauding deserters. Coupled with the relentless exactions of the authorities, the populace had nearly all fled or perished. Venturing deep into the wild hills, the poet witnessed the desolate spectacle of emptied villages and abandoned fields. Employing a descriptive technique approaching pure reportage, he recorded this landscape of ruin wrought jointly by war and tyranny. Though a mere forty characters in length, the poem functions like a tightly framed close-up on the era's open wound, concentrating within it the most deeply sorrowful and austere critical gaze of Du Fu's later years.

First Couplet: “盗贼浮生困,诛求异俗贫。”

Dào zéi fúshēng kùn, zhū qiú yì sú pín.

Bandits torment a life that's but a transient, rootless thing; / Here, crushing levies leave a stranger's customs languishing.

The opening strikes with dual focus, naming the two primary sources of suffering. The term "bandits" possesses a double meaning: it denotes the soldiers and brigands who loot amidst the chaos, yet by implication also refers to the rapacious officials and cruel clerks—in the poet's judgment, the latter are often the greater scourge. The phrase "a life that's but a transient, rootless thing" describes the people's precarious, uncontrollable fate, akin to duckweed adrift. It also carries a philosophical weight, alluding to the Daoist concept of life's inherent fragility and transience, thereby lending the depicted hardship a metaphysical dimension. The line "crushing levies leave a stranger's customs languishing" exposes a systematic deprivation: the authorities' ruthless exploitation of those from different regions or of different customs ("a stranger's") results in a pervasive, foundational poverty. While the two lines are perfectly parallel in form, their critical force cuts straight to the bone.

Second Couplet: “空村惟见鸟,落日未逢人。”

Kōng cūn wéi jiàn niǎo, luòrì wèi féng rén.

The vacant village shows but birds in aimless flight; / The sinking sun—no human form appears till night.

This couplet uses minimal, selected imagery to sketch a scene of heart-stilling desolation. "The vacant village" is the stark result; "shows but birds in aimless flight" serves as its most vivid testament—the traces of human activity have been utterly supplanted by creatures of nature. "The sinking sun—no human form appears till night" adds a layer of temporal despair: from daylight to dusk, a prolonged vigil and search ultimately confirm only "no human form." This denotes not merely visual emptiness but the total retreat of civilization and human presence. The glow of the dying sun casts a bleak, warm light over this wasteland, a contrast that only deepens the pervasive sorrow.

Third Couplet: “步壑风吹面,看松露滴身。”

Bù hè fēng chuī miàn, kàn sōng lù dī shēn.

Treading the gorge, wind buffets keen against my face; / Beneath the pines, watching, dew soaks me in this place.

The poet shifts from the macroscopic, social desolation to the intimate, immediate environment he inhabits. "Treading the gorge" and "Beneath the pines, watching" are two sequential actions, outlining the poet's solitary figure moving along the wild mountain paths, then pausing in contemplative observation. "Wind buffets keen against my face" and "dew soaks me" are the body's most direct sensory experiences—the wind is a tactile cold, the dew a chilling dampness felt on the skin. These lines appear purely descriptive, yet they function to embed the poet himself completely within this landscape of abandonment. He is not a detached observer but an experiencer and physical bearer of this suffering space. That wind and dew are elements of nature, yet can they not also be read as metaphors for the harsh, clammy social climate of that age?

Fourth Couplet: “远山回白首,战地有黄尘。”

Yuǎn shān huí báishǒu, zhàndì yǒu huángchén.

To distant hills I turn my white-crowned, weary head. / On old battlegrounds, tell-tale clouds of dust are spread.

The conclusion pushes the gaze into spatial depth and temporal vastness. "Distant hills" represent silent, eternal nature, a constant frame of reference; "I turn my white-crowned, weary head" is the poet's self-portrait in old age. The verb "turn" contains within it a world of retrospection, reflection, and weary resignation. "On old battlegrounds, tell-tale clouds of dust are spread" abruptly returns the focus to cruel reality—the strife persists; the dust of conflict still rises. The green hills and the yellow dust, eternity and violent turmoil, the poet's white hair and the specter of war are placed here in stark juxtaposition. The poet, figured by his aged, careworn visage, stands at the confluence of enduring nature and immediate history, becoming the most silent yet most potent witness to that anguished time.

Holistic Appreciation

This five-character regulated verse exemplifies the extreme concentration and deep gravity of Du Fu's late style. The entire poem follows an emotional progression of "distress—destitution—emptiness—desolation—chill—despair," its structure as tight and interlocked as wrought iron. The first two couplets focus on the external social tragedy; the latter two turn inward to personal sensation and then outward again to a vast historical perspective. This movement—from outer to inner, then from the proximate to the distant—achieves a sublimation from concrete, immediate reality toward reflections on time and human existence.

The poem's core power derives from the tension it sustains between "absolute silence" and "immense grief." Throughout, there is no loud lament, only the quiet notation of a "vacant village" with birds and a "sinking sun" without people, only the细微 recording of "wind buffets… my face" and "dew soaks me." Yet, precisely within this extreme quiet and these minute physical details lies suppressed a towering fury against the "bandits" and "crushing levies," and permeates a profound compassion for the "transient, rootless" life in distress and the poverty of the "stranger's" land. This technique—using a cool, descriptive brush to depict a fervent heart, using silence to convey depths of indignation—achieves that artistic realm where profound sound resides in apparent stillness.

Artistic Merits

- Precision and Incisiveness of Critique: The opening directly names "bandits" and "crushing levies" without preamble, clearly attributing the people's suffering to the twin scourges of violent disorder and tyrannical governance. This demonstrates the courage and penetrating insight characteristic of Du Fu's "poetic history."

- Selective Accumulation and Layering of Imagery: "Vacant village," "sinking sun," "birds," "wind," "dew," "distant hills," "white-crowned head," "yellow dust"—these individual images are not in themselves extraordinary. Yet, through the poet's discerning selection and deliberate arrangement, they coalesce to construct a unified artistic conception that is desolate, cold, and vast, possessing a powerful pictorial quality and emotional resonance.

- Spatio-Temporal Expansion within Parallel Structure: The parallelism in the two central couplets is finely crafted: "vacant village" parallels "sinking sun" (space vs. time); "treading the gorge" parallels "beneath the pines, watching" (movement vs. still observation); "wind buffets… face" parallels "dew soaks me" (sensation vs. sensation). This formal elegance is matched by a continual shift in perspective within the content, effectively expanding the poem's dimensional scope.

- The Expansive Gravity of the Concluding Couplet: "To distant hills I turn my white-crowned, weary head. / On old battlegrounds, tell-tale clouds of dust are spread" juxtaposes the poet's personal autumn years ("white-crowned head") with the persistent turmoil of the age ("clouds of dust"). The individual's fragile mortality is set against the vast, indifferent backdrop of history, granting the entire poem a conclusion of immense, lingering gravity.

Insights

This work offers insights concerning "how to maintain the courage to gaze unflinchingly upon ruins" and "how to discern profound meaning within utter silence." Du Fu did not avert his eyes from the despair-inducing "vacant village" and the absence of people. Instead, with a poet's feet, he walked into that emptiness; with a poet's body, he felt its wind and dew; and finally, with a poet's vision, he looked toward the enduring hills and the lingering dust of war. He teaches us that genuine moral concern and social critique must begin with the most direct, unvarnished confrontation with suffering.

In our own time, we may no longer face villages emptied by war, yet various forms of "desolation" and "silence"—spiritual emptiness, social alienation, ecological ruin—persist. Du Fu's poem reminds us to attend to those forgotten corners where one "shows but birds" and encounters "no human form," to listen for the subtle messages carried in the "wind" and "dew" that are drowned out by grand narratives, and, with the deep, weary reflection of one who "turns [his] white-crowned… head," to ask why the "clouds of dust" still rise. This quality of steadfast observation in solitude and of compassion that remains undimmed by the prevailing chill is a precious attribute that the reflective mind, across all ages, would do well to preserve.

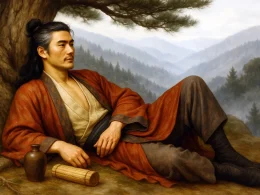

About the poet

Du Fu (杜甫), 712 - 770 AD, was a great poet of the Tang Dynasty, known as the "Sage of Poetry". Born into a declining bureaucratic family, Du Fu had a rough life, and his turbulent and dislocated life made him keenly aware of the plight of the masses. Therefore, his poems were always closely related to the current affairs, reflecting the social life of that era in a more comprehensive way, with profound thoughts and a broad realm. In his poetic art, he was able to combine many styles, forming a unique style of "profound and thick", and becoming a great realist poet in the history of China.