The flowers bloom—but where’s my shadow gone?

I chase perfume through fields alone.

All visions rot with sorrow’s hue,

Even nightingales sing wounds anew.

Woods pulse with lust—swallows mate in silk,

Each knot of passion, each shared milk.

Why probe this gangrene of the heart?

Trees and moss drink the sun’s last art.

Original Poem

「采桑子 · 花前失却游春侣」

冯延巳

花前失却游春侣,独自寻芳。

满目悲凉。纵有笙歌亦断肠。

林间戏蝶帘间燕,各自双双。

忍更思量,绿树青苔半夕阳。

Interpretation

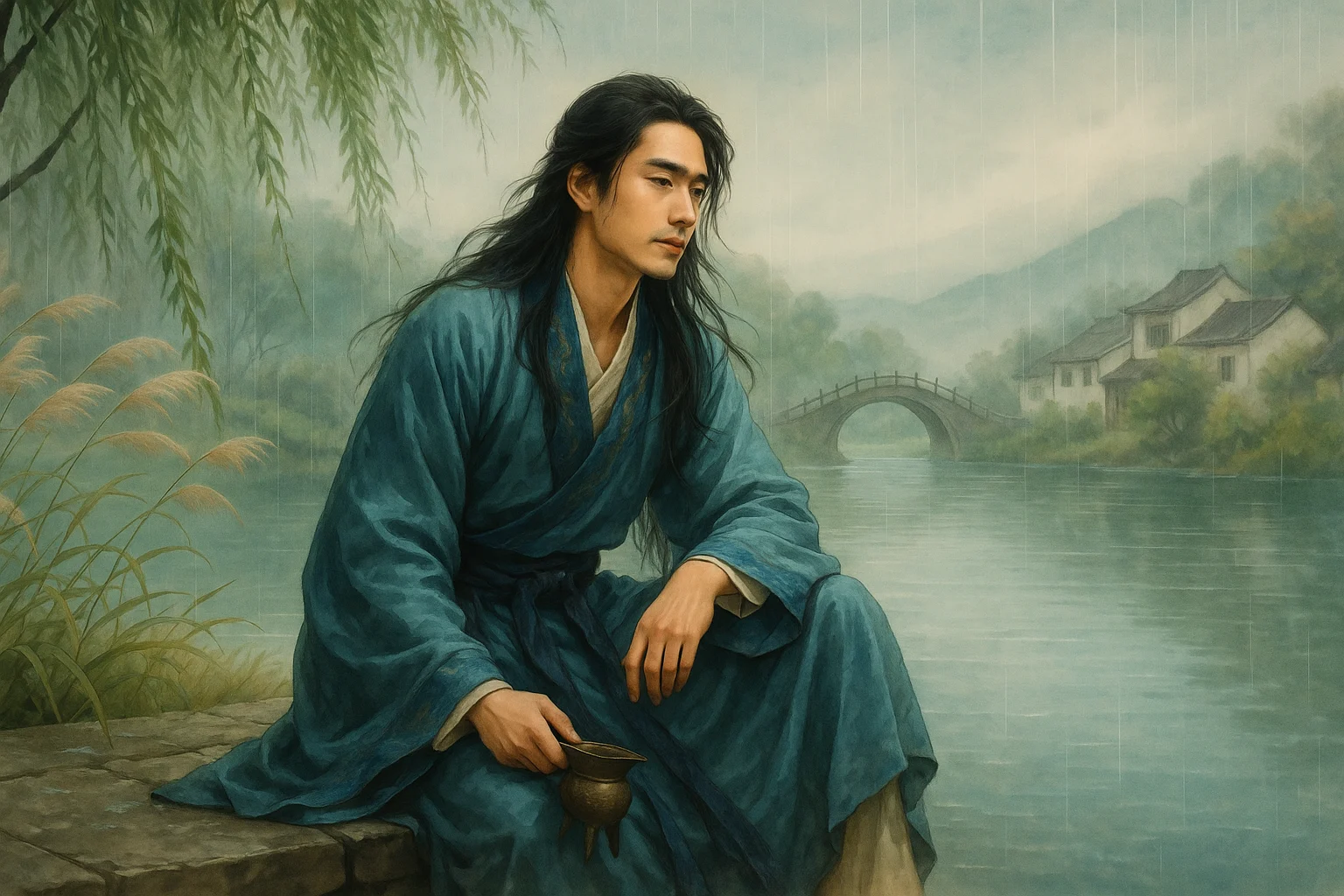

This lyric by Feng Yansi, a master of Southern Tang poetry, paints a poignant scene of solitary spring wanderings after the loss of a beloved companion. Through vivid natural imagery interwoven with profound melancholy, the poem captures the essence of loneliness amidst nature's vibrant renewal, transforming personal grief into a timeless meditation on love and absence.

First Stanza: "花前失却游春侣,独自寻芳。满目悲凉。纵有笙歌亦断肠。"

Huā qián shī què yóu chūn lǚ, dú zì xún fāng. Mǎn mù bēi liáng. Zòng yǒu shēng gē yì duàn cháng.

Before the blossoms, I've lost my springtime companion,

now wandering alone through fragrant paths.

Though surrounded by splendor, my eyes see only desolation—

even festive music pierces my heart.

The stanza opens with a stark admission of loss—"lost my springtime companion" (失却游春侣)—establishing the poem's emotional core. The contrast between nature's vibrancy ("fragrant paths") and the speaker's inner "desolation" (悲凉) heightens the sense of isolation. The closing line's paradox, where joyous "festive music" (笙歌) becomes painful, underscores how solitude distorts perception, making even beauty a source of sorrow.

Second Stanza: "林间戏蝶帘间燕,各自双双。忍更思量,绿树青苔半夕阳。"

Lín jiān xì dié lián jiān yàn, gè zì shuāng shuāng. Rěn gèng sī liang, lǜ shù qīng tái bàn xī yáng.

In the woods, butterflies flirt;

behind curtains, swallows nest—

all creatures in their pairs.

How can I bear to dwell on this?

Green trees, mossy stones,

half-lit by the setting sun.

Here, nature's coupled creatures ("butterflies… swallows") magnify the speaker's solitude. The rhetorical question—"How can I bear to dwell?" (忍更思量)—breaks the poem's lyrical flow, laying bare raw anguish. The final image—"green trees, mossy stones, / half-lit by the setting sun"—melds ecological detail with emotional weight: the "half-lit" (半夕阳) sunset symbolizes fading hope, while moss (青苔) suggests time's slow erosion of grief.

Holistic Appreciation

This ci poem masterfully blends scene and sentiment, using the ostensibly cheerful theme of "spring outings" to subtly convey inner loneliness and loss—a classic example of "writing sorrow through joyful scenery." The first stanza focuses on the "loss of companionship," employing blooming flowers and lively music to contrast the solitary wanderer's melancholy. The second stanza juxtaposes paired butterflies and swallows against the poet's own solitary shadow, culminating in the imagery of the "setting sun" to encapsulate the poem's emotional core.

Without overt emotional outbursts, the poem relies on delicate, nuanced descriptions and symbolic imagery to gradually build a mood of quiet sorrow. Its style is subtle, elegant, and profoundly moving.

Artistic Merits

- Joyful Scenery to Express Sorrow, Heightened by Contrast

The bright spring scenery, paired butterflies and swallows, and melodious music—all typically joyful—are used to accentuate the poet's loneliness. - Vivid, Minute Details

Phrases like "swallows between curtains," "butterflies among trees," and "green moss under trees" are drawn from daily life yet brim with emotional tension. - Scenic Conclusion with Lingering Meaning

The phrase "half-setting sun" not only marks the time but also amplifies the mood, driving the poem's sorrow to its peak. - Concise Language, Exquisite Imagery

The poem is tightly structured with brief lines, yet its emotions run deep, embodying the artistic essence of the lyrical ci tradition.

Insights

This ci conveys the melancholy of "the scenery remains, but the people are gone," reflecting the genuine psychological state of loneliness after losing a close relationship. It reminds us to cherish those around us and value the subtleties of emotion. Moreover, the poet's restrained yet deeply affecting technique showcases the lyrical ci's artistic charm of "profound yet understated emotion," offering future generations a delicate and beautiful model for emotional expression.

About the Poet

Feng Yansi (冯延巳 903 - 960), courtesy name Zhengzhong, was a native of Guangling (modern-day Yangzhou, Jiangsu) and a renowned ci poet of the Southern Tang during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. Rising to the position of Left Vice Director of the Department of State Affairs (Zuo Puye Tongping Zhangshi), he enjoyed the deep trust of Emperor Li Jing. His ci poetry forged a new path beyond the Huajian tradition, directly influencing later masters like Yan Shu and Ouyang Xiu, playing a pivotal role in the transition of ci from "entertainment for musicians" to "literary expression of scholar-officials."