After three ape-cries, tears of longing fall;

This leaf-like boat bears my sick, lonely frame.

Lean not by the window, gazing north or south —

Bright moon or dark, either will sharpen your pain.

Original Poem

「舟夜赠内」

白居易

三声猿后垂乡泪,一叶舟中载病身。

莫凭水窗南北望,月明月暗总愁人。

Interpretation

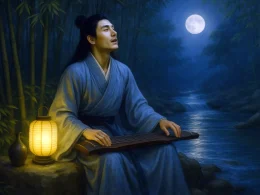

This ancient poem was composed in 815 AD, a year marking a tragic turning point in Bai Juyi’s life. In the sixth month of that year, Chief Minister Wu Yuanheng was assassinated by a provincial warlord. Bai Juyi, bypassing official protocol, was the first to submit a memorial urging the immediate capture of the assassins to restore the nation’s honor. For this, powerful figures at court falsely accused him of "overstepping his authority in state affairs," among other charges, leading to his demotion to the post of Marshal of Jiangzhou. This poem was written during his river journey to that place of exile. Though titled "To My Wife," it is, in essence, the poet’s outpouring to his closest companion of the complex emotions swirling within him on this sudden, frightening journey—a turbulent mix of grief for his shattered career, the sorrows of displacement, and conjugal love. Beneath a tone of consolation surges an irrepressible sorrow, revealing a profoundly personal and poignant facet of Bai Juyi’s poetry.

First Couplet: “三声猿后垂乡泪,一叶舟中载病身。”

Sān shēng yuán hòu chuí xiāng lèi, yī yè zhōu zhōng zǎi bìng shēn.

After the third desolate gibbon cry, my homesick tears fall; / This lone-leaf boat carries our two ailing frames, and that is all.

The opening lines establish a tone of profound distress. "The third desolate gibbon cry" alludes to a famous passage from Li Daoyuan’s Commentary on the Waterways Classic: "The Wu Gorges of Ba Dong are long; / Three gibbon cries, and tears soak your clothes." This allusion directly links the remote, wild landscape, the heartbreaking sound, and the emotional collapse it triggers. "My homesick tears" signify not only the pain of geographical exile but, more poignantly, the tears of failure at being forcibly removed from the political center and the stage for his ideals. The second line powerfully juxtaposes the "lone-leaf boat" with "our two ailing frames." The image is striking: the vastness of the world against the fragility of their vessel; the perils of the journey against the frailty of its passengers. The verb "carries" denotes the boat’s physical load but also symbolizes the heavy burden fate has placed upon this afflicted couple. These two lines move from an auditory stimulus to a visual tableau, from environmental evocation to personal depiction, laying bare the desolation, vulnerability, and helplessness of the journey into exile.

Second Couplet: “莫凭水窗南北望,月明月暗总愁人。”

Mò píng shuǐ chuāng nán běi wàng, yuè míng yuè àn zǒng chóu rén.

Do not lean by the river-window, gazing north and south; / Whether the moon is bright or dim, it will but feed the sorrow in your mouth.

Here, the focus turns to a direct attempt to console his wife, the emotional expression becoming more nuanced and profound. "Do not lean" is an act of restraint, born of tender concern, knowing that gazing out will only deepen sadness. The "river-window" is the cabin’s sole connection to the outside world, yet it also becomes the portal through which sorrow floods in. The phrase "gazing north and south" is saturated with spatial disorientation: south lies the unknown place of exile, Jiangzhou; north, the distant home of Chang’an and his career, now lost. Both directions, if gazed upon, would be heartbreaking. The line "Whether the moon is bright or dim, it will but feed the sorrow" represents both a poetic intensification and a confession of despair. The poet recognizes that in his present state of mind, the objective quality of the scene—its brightness or dimness—has ceased to matter; it will invariably be colored and assimilated by his pervasive sorrow. This is not merely advice to his wife but a statement of his own condition: his inner world has been completely occupied by "sorrow," leaving no room for brightness. This "indiscriminate" sorrow, detached from any specific trigger, is deeper and more absolute.

Holistic Appreciation

This heptasyllabic quatrain carries immense emotional weight within its economical form. The poem employs a dual narrative perspective of "inner and outer interweaving." The first couplet is outward-facing, describing the desolate environment outside the boat (gibbons’ cries) and the harsh reality within (ailing bodies adrift), a stark depiction of circumstance. The second couplet turns inward, becoming an intimate murmur between husband and wife, where the attempt at consolation lays bare their shared, boundless grief—a psychological confession. The four lines form a complete emotional circuit: from an external stimulus causing inner anguish (gibbons’ cries and tears), to that inner anguish negating any possible solace from the external world (even the moon deepens sorrow). The language is as plain as domestic speech, yet, because it springs from the deepest pain, every word carries heavy meaning, shaking the reader’s soul.

Artistic Merits

- Seamless Fusion of Allusion and Immediate Scene: The allusion to the "third desolate gibbon cry" is not a pedantic display of learning. It aligns perfectly with the southern river journey of exile. The emotional connotation of the allusion (misery, displacement) merges seamlessly with the poet’s present plight, enhancing the historical resonance and the universality of the tragedy.

- Precise Parallelism Coupled with Immense Emotional Tension: The parallelism is exact: "Three sounds" pairs with "lone-leaf"; "after gibbons" with "in boat"; "homesick tears fall" with "ailing frames…all." Yet, beneath this formal precision lies a powerful convergence of multiple contrasts and layers—sound versus image, animal versus human, emotion versus physicality—generating intense emotional force within the strict structure.

- The Indirect Technique of Expressing Sorrow Through Consolation: The poem’s central theme is the expression of "sorrow," yet the final couplet presents it through the act of advising "Do not lean" and the conclusive statement "it will but feed the sorrow." This "expression through negation" means the grief is not poured out directly. Instead, it becomes all the more profound and inescapable when conveyed through a tone of restraint and concern, reflecting emotional complexity and artistic subtlety.

- The Oppressive, Confined Quality of Spatial Imagery: Images throughout the poem—"lone-leaf boat," "river-window"—create a sense of confinement and entrapment. "Gazing north and south" hints at an external world that is both unreachable and fraught. This spatial arrangement is a masterful symbol of the poet’s psychological landscape: politically confined, stranded in life with no clear way forward or back.

Insights

This work reveals Bai Juyi not only as a poet of "leisurely contentment" but also of "heartfelt lament"; he is philosophical, yet also profoundly affectionate. The poem lays bare the most genuine vulnerability and pain of a scholar-official facing immense political reversal. Yet, it is precisely within this absolute predicament that the detail of ailing bodies leaning on each other and the spousal solace of this "gift to my wife" shimmer with human warmth and the strength of ethical bonds. It tells us this: an individual’s sense of powerlessness before history’s torrents and the system’s crushing weight may be timeless. However, the close bonds of responsibility and affection between people form the final bulwark against life’s desolate cold and the essential foundation for preserving human dignity.

The poet’s advice to his wife, "Do not lean by the river-window," stems from a keen understanding of the torment of hoping yet finding nothing. This wariness and pessimism towards "hope" itself is a visceral life experience. It reveals that true courage lies not always in blind optimism, but sometimes in seeing clearly that the situation "will but feed the sorrow" regardless, and yet still choosing to "carry" that ailing body forward together with a loved one. This warmth of mutual support within despair is the core power of this poem, allowing it to move us across a thousand years.

About the Poet

Bai Juyi (白居易), 772 - 846 AD, was originally from Taiyuan, then moved to Weinan in Shaanxi. Bai Juyi was the most prolific poet of the Tang Dynasty, with poems in the categories of satirical oracles, idleness, sentimentality, and miscellaneous rhythms, and the most influential poet after Li Bai Du Fu.